The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

No one would argue the assertion that Hugh Templin was the greatest newspaperman in the history of Wellington County.

He presided as editor-publisher of the Fergus News Record from 1939 until 1963, and as editor during the 1920s and 1930s. He wrote for the paper over a longer term, from 1918 until ill health forced him to abandon his office Underwood in 1969 – a record of 51 years that still stands in Wellington.

Printer’s ink was in Hugh Templin’s blood. He grew up in the newspaper office of the Fergus News Record. Through his ancestors on both sides of his family, he had deep roots in the Fergus area. Hugh followed in the footsteps of his father John C. Templin and his grandfather John Templin. The three generations influenced the development of Fergus for over 100 years.

The Templin family came from Pomerania, a province of Prussia on the Baltic Sea. Hugh’s grandfather, John, was born there in 1839, but came with his family to Canada while still a youngster.

John Templin trained as a blacksmith and carriage maker, and came to Fergus in the 1860s. He soon established a solid business on St. Andrew Street East, expanding several times in the 1870s and 1880s.

At the age of 26, John Templin married Maria Ann Cowan. The couple produced a family of four, the eldest of whom, John C., was Hugh Templin’s father.

Born in 1869, John C. proved to be a top student at the Fergus public and high schools. Though he had a lifelong fascination with mechanical equipment, he had no interest in his father’s business. He took the teacher training course at the Elora Model School, and then taught at Marsville for several years. He then spent a year at the Ottawa teacher’s college. When he returned to Fergus, he took over the Grade 5 and 6 classes at the Fergus school.

John C. married Annie Black in 1894. She was a great granddaughter of Hugh Black, who had operated the first tavern in Fergus in the 1830s. Her father had been a figure in the sawmill business for years. Hugh Charles Templin, born in 1896, was their first child; two daughters followed later.

In 1902, perhaps fulfilling some long-held dream, John C. purchased the Fergus News Record from the widow of John Craig, who had been proprietor since 1868. The paper had been declining for several years, a consequence of Craig’s declining health and advancing age. Three years before, an upstart, the Fergus Canadian, had commenced publication, and had cut into the News Record’s advertising and circulation.

John C. Templin possessed wide interests, and indulged them as much as he could. Among other things, he raised fancy pheasants, and spent many hours breeding roses. He could not resist new technology and machinery: he had one of the first residential telephones in Fergus, he pursued photography with great enthusiasm, and purchased the first Edison phonograph in town.

Though he wielded a blue pencil as editor, John did not give up his teaching position for several years, until the paper achieved a more solid financial footing. His habit was to drop into the office for a couple of hours before classes, and again for a while in late afternoon. The News Record was then issuing from an upstairs office on St. David Street, a few doors north of St. Andrew. The press, powered by a gasoline engine, sat in an addition at the rear.

Every time a printing equipment salesman passed through town, John drooled at the new equipment available. He upgraded the printing press a couple of times, and installed the first linotype in the county. This complex and expensive machine set type faster than anyone could do by hand.

The electric generating plant owned by Dr. Abraham Groves was situated just a stone’s throw away. Templin and the doctor soon tried an experiment. They attached a large direct current motor to the press, connected by wire to the generator down the street. Each week at press time, Jim Wilson, the power plant operator, fired up the plant to print that week’s issue of the paper (the tight-fisted Dr. Groves normally did not turn the power on until dusk).

It was a hopelessly inefficient system, and it did not last long. Differences erupted between Groves and John Templin, and persisted for the rest of their lives. The gas engine resumed its role in powering the press.

Young Hugh Templin hung around the newspaper office from the time his father purchased it. Soon he was an unpaid employee, running around downtown to pick up advertising copy, deliver bills, and other duties like telling Wilson to turn the power on.

The cramped office on St. David Street eventually proved inadequate. Larger quarters on St. Andrew Street became available in 1914, when an egg pickling plant closed. Templin moved the paper there after renovating the building. It still stands, immediately to the east of the Grand Theatre.

Like his father, Hugh turned out to be an excellent student, making a name for himself at both the public and high schools. John C. Templin eventually gave up his teaching position to devote more time to the paper, and young Hugh spent much of his spare time there as well, acquainting himself with all the skills required in a small-town newspaper office.

After graduating in 1915, the tall gangly youth set off for the University of Toronto, where he majored in modern history.

In 1917, Hugh interrupted his studies to enrol in the military. After training, authorities assigned him to the signal corps as a cyclist and messenger. A minor injury ended his military career, and he was sent back to Canada.

Hugh intended to resume his university studies, but soon he got a call from home. An ankle injury had immobilized his father. Help was required with the paper. Hugh took over as interim editor. He began penning the editorials, and did so with sufficient skill that his father assigned the duty to him personally.

Young and ambitious, Hugh Templin did not wish to spend his time in Fergus. When his father recovered, Hugh returned to Toronto and his university classes, mailing editorials home every week.

In 1920, he landed a civil service job with the United Farmers government of E.C Drury. Initially dazzled by working in the corridors of power, he soon grew jaded.

“I saw enough of politics to do a lifetime,” he later recalled.

His situation grew decidedly sticky when some of his editorials castigated his employer: the United Farmers government. The attorney general, W.E. Raney, sat for East Wellington, the riding containing Fergus.

Soon after joining the civil service, Hugh got married. He had known his bride, Laura Dow, for years. She was the daughter of Dr. Dow of Belwood. He had moved his family and his practice to Toronto in 1914 to permit his children an advanced education. Laura had recently graduated from teachers college.

In addition to his government work and his weekly editorials, Hugh Templin began to cultivate Toronto newspaper people. This led to some freelance work with the Toronto Star, and eventually with other publications.

In 1924, with a wife and young son to support, Hugh returned to Fergus to take charge of the paper during a European trip by his father. Though he had intentions of returning to Toronto, he never left Fergus again except for brief trips.

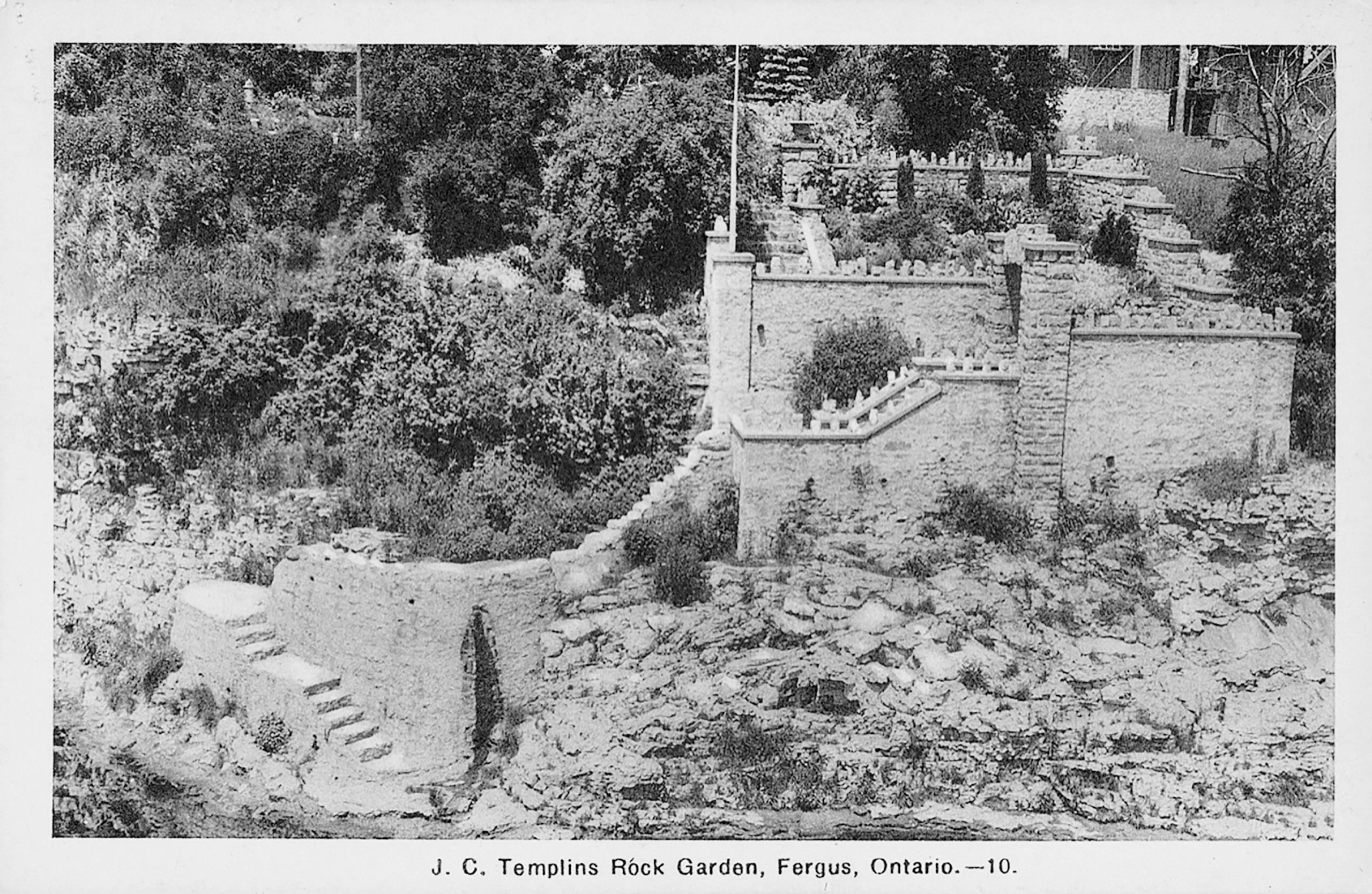

Gradually, Hugh took over most of the editorial duties of the News Record, while his father, whose health was declining, spent his time puttering with his roses, and made plans for his garden at the rear of the office, portions of which survive and have been restored as Templin Gardens.

As well, Hugh continued with his freelance work through the 1920s and early 1930s. His work ran in Maclean’s Magazine, Saturday Night, the Star Weekly, and the Financial Post.

The Star Weekly pieces, written under the name of Ephraim Acres, were thinly disguised satires of life and politics in the Fergus area. When the pressures of other business forced Hugh Templin to stop writing them, noted author Greg Clark took over the task of writing humorous rural features.

When he returned to Fergus, Hugh took up one of his father’s new hobbies: radio. He penned a weekly radio feature, giving tips on ways to improve reception, reports on new stations, and news of new technical advances. Often, the editor appeared at the office in the morning, red-eyed after sitting up all night with his radio.

More significant for Hugh Templin’s career over the coming decade were friendships he struck up with two people: Robert Kerr and John Connon.

Both were older, and in some ways mentors to Hugh, who was still in his early 30s. Kerr would inspire Templin’s pioneering crusade for conservation, and Connon would inspire explorations into local history.

(Next week: part two of the story of the Templin family).

*This column was originally published in the Wellington Advertiser on April 18, 2003.