Want to listen instead? Click or tap play above.

*Caution: This story contains graphic details that may be upsetting.

SOUTHGATE – One of the last photos Monica Chisar posted to Facebook was on July 3, 2018.

She appears to be lying down, posed with pursed lips. Her eyes are obscured by a face filter adding digital effects to the photo. The caption reads: “Manchester Airport massive delay.”

Three days later, Monica publishes a selfie on Instagram – it too with a face filter. It’s hash-tagged “airplane” and “sleepytime.”

It would be the last time the 29-year-old would ever post about her life. After July 6, 2018, her accounts go quiet.

Monica was a prolific user of social media, using filters and emoticons to express herself online.

She was the type to share a photo of her morning coffee, or sojourns through places such as Portugal and Cuba.

In unfiltered photos, Monica’s piercing eyes, framed by dark eyeliner, look directly into the camera; her straight, dark hair runs past her shoulders.

“She loved using social media,” her half sister Amanda Chisar told the Advertiser by phone.

Monica’s mother immigrated to Canada from Moldova in 1979. She later relocated to Ontario from Manitoba, with Monica’s Romanian father, in 1986. They later split in 1990.

Monica Chisar in Grade 2, when she was seven years old. Submitted photo

Amanda was 11 when she first met Monica, who was 14 at the time, in Toronto. The two became inseparable.

“She taught me how to do my makeup, how to dress,” Amanda said.

When Monica became pregnant with her son, Ethan, the two moved in together.

“She was so loving, she did so much for her family; she was a fun, energetic, beautiful person,” Amanda said.

Monica loved getting dressed up to go out and dance to salsa, samba and bachata.

She was outgoing and always the life of the party, Amanda said. “That was Monica.”

Amanda became worried after Monica’s social media posts stopped and she heard nothing from her sister after Monica returned from her trip.

She kept saying “something’s wrong.” Amanda’s concern grew after family and friends hadn’t heard from her either.

But Monica was a “free-spirited person” who lived her own life and would drop off the radar only to later pop up again.

Monica was last seen by a friend after being dropped off at the corner of Barton Street and Parkdale Avenue in Hamilton on the night of July 11, 2018.

It wasn’t until Sept. 28 of that year Amanda reported Monica as missing to Hamilton police.

This photo, taken in Hamilton on June 8, 2018, was the last time Amanda Chisar, left, would see her sister Monica Chisar alive. Monica was just 29 years old. Submitted photo

A November 2018 press release stated police were looking for a 5’7”, 170-pound woman with green eyes and shoulder-length reddish/brown hair.

She had a small star tattoo on the left side of her neck, a crown on her left wrist, and tattooed on her upper back were “Ethan” and “I love my daddy FC.”

Amanda wondered if her sister was locked in a basement, crying for help.

She described it as the “worst possible feeling I’ve ever had.”

* * *

It was just below freezing on a clear Christmas Eve afternoon in 2019.

Trevor Caudle and his son crunched through the snow at the back edge of his wooded property, about 10km north of Mount Forest in Southgate Township.

Caudle swung a hatchet, cutting blazes into the cedar trees.

Over the fence line he noticed a purple suitcase strapped to a rusted green moving dolly poking out from the snow and brush.

The area is a regular dumping ground, with litter strewn along a narrow gravel roadway running west to east between Highway 6 and Sideroad 33.

Caudle sliced into the suitcase nylon with his hatchet, through the floral patterned fabric inside, and peered through the narrow opening.

Inside was a human skull. Caudle had just discovered Monica Chisar’s remains.

“It’s not very pleasant,” Caudle said by phone.

Monica Chisar’s remains were found in a suitcase strapped to a moving dolly and discarded in wooded area north of Mount Forest. Submitted photo

Sitting around the dinner table that Christmas Eve night, the family spoke about the grisly discovery.

Caudle had found dead animals, including deer and dog carcasses he said were dumped in the area, but never a human body.

He owned the rural property for more than a decade, but has since moved.

He followed news reporting in the years after, hearing Monica’s name for the first time on the radio.

More than a year later, he said, “you still think of it, especially with a name.”

* * *

Grey-Bruce detective sergeant Byron Schwass was working Christmas Eve when the call came over the radio.

“I started driving towards it, never thinking it was actually going to be this,” Schwass said in an interview.

He had dealt with many calls for found remains over his 35 years in policing; most of the time bones came back to decomposed animals.

Along with forensic identification officer Peter Peschke, Schwass arrived to find a suitcase wrapped with different fabrics, secured to a moving dolly with straps and a chain.

“As soon as I seen the suitcase, and the fact it was tied onto a moving dolly, and where it was, basically I didn’t like the look of that at all,” Schwass said.

Schwass and Peschke looked at the decomposing remains inside through the sliced opening.

The officers had no idea who it was, or how the remains got there.

“I’m always drawn to figure out who it is, and ‘what happened here, what led to this person being here like this?” Schwass said.

The dolly and suitcase had long since settled into the soft ground of the cedar bush and were frozen there.

With the scene secured, and a tent placed over the evidence, police spent the Christmas holidays in the bush as propane and electric heaters wore away at the cold.

Two days later, on Dec. 27, Monica’s remains were sent to the province’s Forensic Pathology lab in Toronto for a postmortem.

The coroner’s identification tag read: “unidentified.”

* * *

In an investigation against the odds, police did get a significant lucky break early on.

A piece of Monica’s identification was found in the suitcase.

“I Googled her name, and she’s a missing person out of Hamilton,” Schwass said.

“That’s how we believed we had Monica Chisar.”

A DNA sample from Monica’s father later confirmed her identity, but police were still without suspects in what had become an active homicide investigation.

A plea for tips on May 12, 2020 by Hamilton police staff sergeant Jim Calendar and OPP detective Scott Moore, with the Criminal Investigation Branch (CIB), seemed to fall on deaf ears.

“We were hoping that the big press release when we identified her body and all that was going to generate some activity,” Schwass said.

“It really didn’t … This was a cold case.”

* * *

Brad Olsen, a new detective in Schwass’ unit at the time, was tasked as the lead investigator.

He couldn’t let go of the case, his first homicide.

Even as Grey-Bruce was hammered with new cases in 2020, Olsen continued working quietly in the background to bring justice for Monica, building what eventually became a massive file.

Following the snap retirement of Moore, the CIB detective originally tasked with managing the case, detective MaryLouise Kearns agreed to come on at Olsen’s behest.

Kearns, with her belief in “old-school policing,” reinvigorated the case, eventually leading to a suspect.

To work a resource-intensive investigation, Kearns needed buy-in from Hamilton.

She began connecting with old contacts there, formed over more than three decades behind the badge, to reignite interest in the case.

The city and province agreed to a joint investigation, but it would ultimately be the OPP that took the lead, building on the early ground work laid by Hamilton police.

Kearns asked Hamilton for detectives experienced in the ways of “old-school policing,” before a reliance on technology became the norm.

By the time Monica’s remains were found, digital records that would have assisted investigators were gone.

Kearns wanted cops who, armed with nothing, could hit the ground and work sources, shaking information loose to move the investigation forward.

Hamilton detective Angela Abrams and Bez Imeri, a relatively inexperienced uniform cop, were assigned.

By the spring of 2021, investigators were working the case out of a Wilson Avenue office space in Hamilton, including four detectives from the OPP: Jillian Serkowney, Brad Olsen, Paula King and Mike Waechter (the latter two have since retired).

Grey-Bruce Detective Sergeant Byron Schwass, left, and Caledon OPP Detachment Commander MaryLouise Kearns, who was a Detective Inspector with the OPP’s Criminal Investigation Branch at the time she was working the Monica Chisar case. Photo by Jordan Snobelen

The detectives focused on people identified by Hamilton police as persons of interest when Monica was considered a missing person.

Police started talking to Monica’s family before moving on to her associates in Hamilton.

“It led us into this Albanian community,” Schwass said, adding investigators faced “a huge language barrier.”

“It became very obvious that people weren’t telling us the truth,” Schwass said.

Imeri, paired up with detectives Abrams and King, acted as a translator, allowing police to make inroads.

“We actually started developing some connections and leads … one interesting thing led to another,” Schwass said.

Eventually police got a nickname: Blerim.

“We didn’t know who this guy was,” Schwass said.

“We wound up being able to bounce from one person to the next, to the next … we were getting closer and closer to where he was,” Schwass said.

Old-school policing may have brought the case back to life, but technology would keep it going.

Without warrants and authorization from the courts to tap cellphones, the case would have remained cold.

“We would have known we were looking at the right people, but basically it was all the warrant writing behind the scenes that led to it,” Schwass said.

Police learned Blerim switched phones regularly, and was a big social media user and online dater.

It would be his online activity that allowed police to move beyond a nickname and discover Blerim’s true identity.

Ahmet Nikci, a Kosovo expat, entered Canada illegally from the U.S. in 2012.

At the time, he was facing up to seven years in a U.S. prison after being convicted for punching and severely injuring someone in New York state.

According to Schwass, Hamilton’s Albanian community has a habit of harbouring illegals from the U.S. in exchange for under-the-table work here.

Nikci was put up in a Melvin Avenue apartment in Hamilton, where Monica wound up staying within a week of returning to Ontario.

Monica’s diluted blood would later be found on a baseboard in the apartment, likely from a cleanup job after she died there.

* * *

On July 19, 2021, Nikci was being watched by a surveillance team while he smoked outside on a balcony.

Police couldn’t yet pin him with Monica’s death, but they were able to arrest him on immigration grounds.

“As soon as he came out onto the sidewalk, we arrested him,” Schwass said.

Nikci was being held at Milton’s Maplehurst Correctional Complex when he gave a three-hour statement to OPP detective Steve Coburn admitting to being with Monica in the early morning hours of July 11, 2018.

He claimed Monica was high on drugs and struck her head on a mirror when jumping. There was blood and what he believed to be brains coming from her head, he stated.

“I was the only one who knew what happened,” he told Coburn, adding he was “with her when she took her last breath.”

But Nikci never called 911 or reported what he claims happened.

Instead, Monica’s body remained in the apartment for two days.

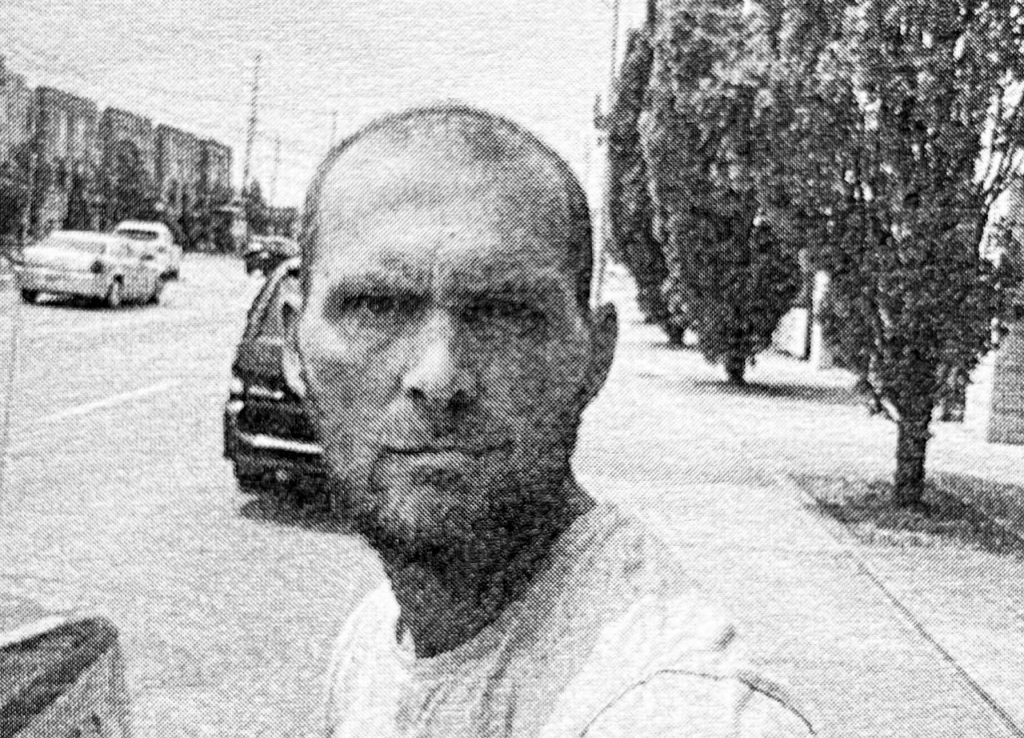

Ahmet Nikci is seen at the time of his arrest in Hamilton in 2021. Submitted photo

He called a contact known as Rahoul, who Nikci stated had “moved bodies” in Mexico, to help dispose of Monica.

Nikci paid Rahoul $1,700 and encouraged him to dismember Monica’s body to fit it into her suitcase.

A postmortem examination by forensic pathologist Dr. Michael Pollanen and forensic anthropologist Dr. Kathy Gruspier revealed a 3.5-centimetre chop to Monica’s skull, running from her nose to her forehead.

The postmortem also noted four cut marks, and blunt impacts to a side of her skull, as well as six cut marks to the upper half of her thighbone.

Days after Monica took her final breath in June 2018, her broken body is driven 120km from Hamilton.

Her remains are discarded in the woods, her belongings strewn across the country road.

Police charge Nikci with second-degree murder and interfering with Monica’s remains.

Nikci never admits to killing her.

* * *

The second-degree charge was later reduced in Hamilton court to a count of counselling someone to interfere with human remains.

Pollanen, the forensic pathologist, concluded Monica died because of a head injury, likely due to brain trauma and bleeding.

But because her remains were so decomposed, it couldn’t be definitively concluded when her injuries occurred – before or after death.

“We’re not going to get him for second-degree murder, what else can we get him for?” Schwass said.

Schwass and Kearns said the prosecution was salvaging what it could from the case to put Nikci away for as long as possible.

“The counselling to commit an offence — I’ve never seen that done before by a Crown, and that was her idea,” Schwass said of prosecutor Cheryl Gzik.

(Gzik did not respond to an email from the Advertiser.)

Nikci pleaded guilty in Hamilton court on Dec. 6, 2022 to the lesser counselling charge, and to interfering with Monica’s remains.

Gzik and Nikci’s defence lawyer David Newton both asked for a sentence of three years on the lesser charge, and the maximum of five years on the interference charge, for a total of eight years.

Monica Chisar’s remains were found near Southgate Road 10, running between Highway 6 to the west, and Sideroad 33 to the east. Photo by Jordan Snobelen

“It was very short time when I met Monica, it was not even two weeks; [she] was good person,” Nikci told the court.

“It was not meant to be,” he said, adding he hoped to meet her “in paradise somewhere.”

“In some cases like this one, the truth of what happened has been eradicated,” Justice Anthony Leitch said.

“Exactly how she met her death cannot be ascertained from the remains themselves.”

The court, he continued, was forced to accept “the defendant’s version of Monica Chisar’s last moments.”

“I have deep suspicions that something else happened to Monica Chisar,” the judge said.

“I deeply suspect you know more than what you admitted to police.”

“She deserved, as all people do, to have her remains dealt with in a dignified way, as her family saw fit,” he continued.

“You stole that from her and all of those who loved her.”

“I’m sure everyone in this room wishes you had not chosen to come to our country,” Leitch said.

The judge accepted the joint crown-defence sentencing submission.

With credit for time already served and harsh jail conditions, Nikci was handed five years and eight months to serve in a federal penitentiary.

After his sentence expires on Aug. 5, 2028, it’s expected he will be turned over to U.S. authorities to be dealt with there, and eventually deported to Kosovo.

* * *

In her victim impact statement, read aloud in court, Amanda said Monica’s young son “will never get a chance to know his mother.”

“I know one of the kindest people to live will never be seen again, and all I have left of her is pictures, her inspirational messages of love and hope, and my memories of her,” Amanda told the court.

She shared with the Advertiser a message Monica wrote when she was 16:

I love you very, very much, don’t forget that. Come and talk to me whenever you want, I’m not far away, I’m just in the next bed to yours. Love your sister, Monica.

Amanda said her sister was portrayed in court as a drug-addled partier who brought about her own suffering.

“Monica deserved better,” she remarked.

“I think Monica didn’t get justice; I don’t think the sentencing was even remotely fair,” she said as she broke down and sobbed.

“I think my sister was brutally murdered. I miss my sister so much.”

A memorial bench dedicated to Monica Chisar’s memory sits beneath a maple tree in Toronto’s Beth Tzedec Memorial Park. Photo by Jordan Snobelen

These days Amanda is trying to mourn Monica less and celebrate the life she did have.

“I’ve tried to live my life with her like a guardian angel of sorts,” Amanda said. “She’s literally a part of everything.”

Amanda plans on spreading Monica’s ashes in Mexico, where her son now lives with his father, and has started a GoFundMe campaign to raise money for the trip there.

* * *

“Justice is never fitting to the crime, truly it never is, especially for a family,” Kearns said.

Solace can perhaps be found knowing police caught someone who at the very least played a role in Monica’s death.

“I’m happy we were able to bring some peace to her and the family,” Kearns said.

The detectives are both convinced there is more to the case that couldn’t be proven in court.

“We know she was murdered,” Schwass said.

“And we also know that there’s at least one other person involved,” Kearns added.

Neither was willing to divulge more, they said to protect the integrity of a case years in the making.

“We have one shot at making something stick, and if you miss it, you miss it,” Schwass said.

“Someone in the Hamilton community knows,” Kearns said.