The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

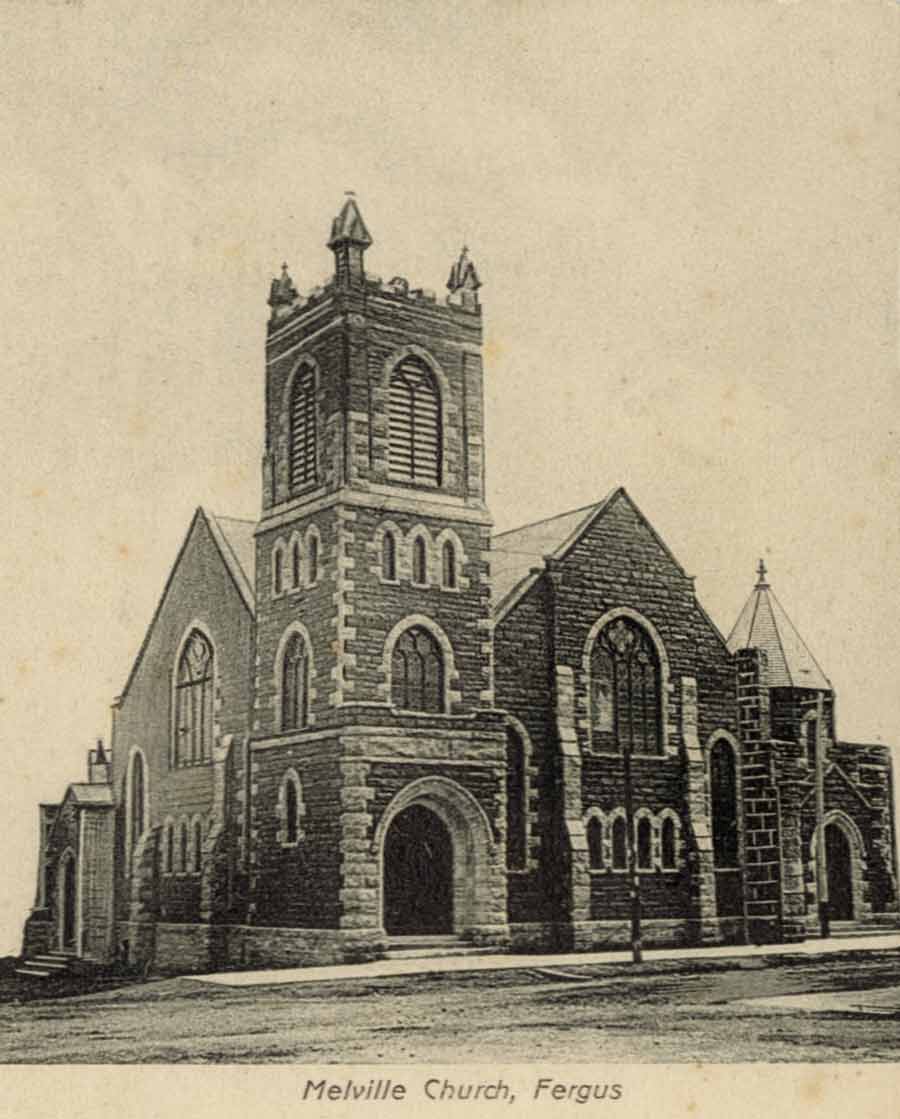

Note: This is a continuation of a brief history of Melville Church in Fergus.

In his first two years in Fergus, beginning in 1896, Rev. John McVicar restored the vitality that Melville Presbyterian Church had enjoyed when Rev. George Smellie was in his prime.

Attendance at the church had peaked in the 1870s, and since then had been falling slightly. The old church on Union Street, completed in 1847 and expanded in 1861, possessed many deficiencies: the seating was cramped and uncomfortable, and the building was impossible to heat properly. McVicar pursued the idea of replacing the building, first considered in the mid 1870s.

Under McVicar’s guidance, a building committee got to work in Nov. 1898. Before the month was over, an acrimonious controversy erupted over a site. It was obvious that the existing building sat on a lot that was too small (this property is immediately west of the present tennis courts on Union Street).

The obvious solution was to approach the town for additional land on the east side of the existing church. This land had been surveyed as a market square in the original plan of Fergus, but had never been developed for any purpose.

The farmers in the congregation objected to the site. There was no shelter for their horses, sleighs and wagons at that site. They wanted something close to the main street, so they could use the driving sheds maintained by the hotels. This had been a complaint for decades, and they wanted it rectified.

The committee received offers of two other lots, both at the corner of St. David and Queen Streets. These were closer to downtown, but they still required a brief walk to the driving sheds at the rear of the hotels. The swimming pool and the W.G. Beatty estate later occupied these lots.

Most farmers preferred another option, at St. Andrew and Tower Streets. The west end of St. Andrews Street had not developed as much as the east end, and a large lot was available at the corner.

The North American Hotel’s huge driving shed sat across the street, and that of the Commercial Hotel was a mere stone’s throw away. In the end, the farmers prevailed.

Early in 1899, the building committee sought an architect. Louis C. Wideman of Guelph accepted the commission, and agreed to design a structure within the $12,000 budget established by the congregation.

The German-born Wideman worked for only a few years in Guelph before setting out for the Cobalt mineral rush in 1903. One of his larger projects in the Royal City was the addition to the old post office/customs house on St. George’s Square.

With the assistance of H.J. Powell of Stratford, Wideman produced a substantial and tasteful design, specifying Credit Valley sandstone for the exterior walls, with limestone accents. A tower would anchor the building to the corner of St. Andrew and Tower Streets.

The building committee, headed by cattle dealer Hugh Black, advertised for tenders in March. They suffered Presbyterian apoplexy when they added up the tenders: about $19,000, or more than 50% above Wideman’s low-ball estimate.

The result was a flurry of committee meetings, and tense negotiations among Black’s committee, Wideman, and the low bidders. One alternative was to use local stone, excavated from Gow’s quarry just across the river, but this would save less than $2,000, and would not show off the design to its full advantage.

No one really wanted to reduce the size of the building or simplify its design, and so very few economies could be found.

In the end, Wideman drew a simplified design for the tower, and agreed to base his fees on his $12,000 estimate, not on the final price. After a month of bickering, the building committee managed to get the price down to $16,000.

An astute man in business matters, Hugh Black wanted work to start as soon as possible. He feared some other crisis popping up. At one meeting, a couple of the elders wanted the revised design and budget put to a vote of the congregation, but their motion failed to pass.

Black was determined to get the bulk of the work done in 1899. This was a big project, and he wanted to waste no time. He was also worried about the extra money, but the subscription committee agreed to raise an additional $2,500 before the building opened.

The building committee signed the major contracts on April 11: framing and carpentry to Clemens & Co. of Guelph, stone work to Thomas Irving & Co. of Guelph, painting and plastering to Reynolds & Co. of Guelph, and ironwork to Robert Kerr, of Fergus.

Wideman would continue with the project, acting as supervisor, a position today normally called project manager. There was no general contractor.

Excavation work got under way immediately, and Clemens was soon hauling in his large limestone blocks for the foundation. Pleased with the excellent progress, Hugh Black suggested June 8, 1899 for the cornerstone ceremony.

The big event, scheduled for 5pm on a sunny Thursday afternoon, drew more than 1,000 spectators. More than 20 ministers from outside Fergus attended, as well as all the clergy of the town.

The minister, John McVicar, kept the program moving. Melville choir and the Fergus Brass Band provided music. The choir sang a hymn written by Rev. J. B. McMullen for the occasion, and the moderator of the Presbyterian Church in Canada, Rev. Dr. Torrance, delivered an inspiring address.

The large cornerstone contained a copper box filled with papers and information about the church. Margaret Smellie, hearty and proud at 84, agreed to officiate. Her late husband, Rev. George Smellie, had spent the bulk of his life building up the congregation. His shadow loomed over the ceremony: every speaker that afternoon mentioned him.

With the stone in place, the crowd retired next door to the town hall for lunch and another round of speeches.

Construction proceeded smoothly and quickly through the summer of 1899. Then tragedy hit the project. John Moffat had a subcontract to make and place the large roof trusses on the new building. At 68, he was a veteran at the trade, and had been the top builder in Fergus since the 1870s. As he and his men guided the third truss into place, a guide rope broke.

Everyone, including Moffat, ran for safety, but Moffat didn’t move far enough. The truss, consisting of two tons of timber and iron, struck him in the back.

Moffat’s son, John Jr., watched helplessly from the top of the wall – he had been guiding the truss into place. Frantic to help his father, John had to be restrained from jumping off the wall. Moffat’s horrified men picked him up carefully and carried his limp body to a nearby house, as blood streamed from his nose.

Nothing could be done. His back was broken in two places.

Well known and popular, Moffat had built a good portion of Fergus and dozens of farmhouses in the surrounding area. His death produced a mood of gloom in Fergus.

The mood was solemn as construction continued through the fall. The roof was on before bad weather arrived, allowing crews to complete the inside work in relative comfort.

Louis Wideman advised the building committee that the church would be completed by the first week of May. As usual, he was a little optimistic. Work slowed down until early spring.

Then everyone realized that the opening was only six weeks away.

The next month saw a mad scramble to finish the work. Wideman’s design called for four staircases to the gallery, and some intricate interior woodworking. As well, there was a heating system, run from three furnaces in the basement, and a full electric lighting system.

Miraculously, all the interior work, including cleanup, did get finished by the first week of May.

On May 2, Rev. John McVicar sent out invitations to what would be the largest and most impressive church opening in the history of Wellington County.

*This column was originally published in the Wellington Advertiser on Jan. 31, 2003.