The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

Note: This is the conclusion of a three-part series about Melville Church in Fergus.

The Fergus News Record’s issue of May 17, 1900 ran the largest headline in its history above the story of the opening of Melville Church, held four days previously.

In an age when religion was paramount, it was fitting that the largest church in the county outside Guelph should be so honoured.

Rev. John MacVicar preached the last services in the old church a week earlier, and had closed the old building on the intervening Wednesday, as construction crews rushed to tidy up the new structure.

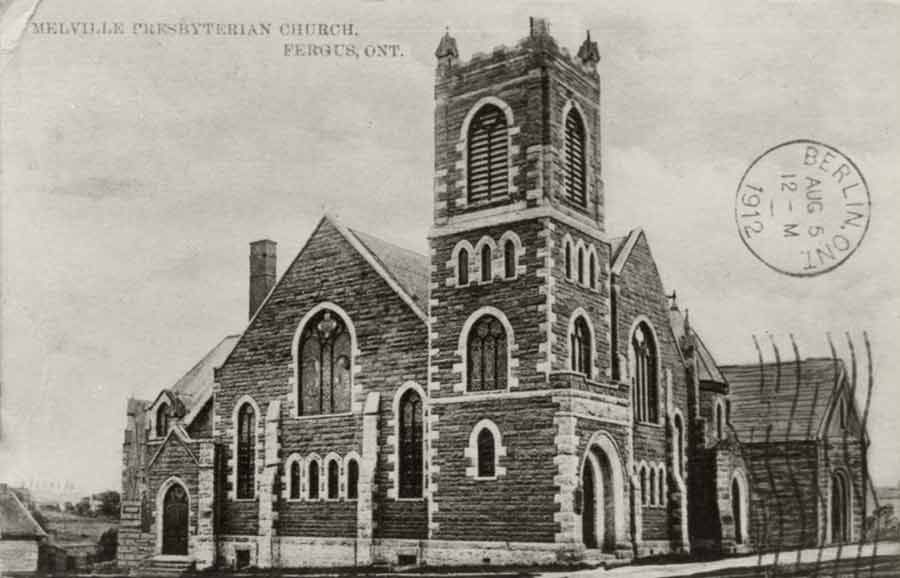

The corner of St. Andrews and Tower Streets had become somewhat seedy by 1900. The new Melville Church, with its dominant tower and red sandstone facade, changed all that.

Inside, architect Louis Wideman had designed a horseshoe-shaped gallery, with the woodwork all golden oak and the plastered walls left white. Polished brass fixtures provided ample electric light. The blend of lines and curves lent a gracefulness to the whole interior that placed it ranks above any of the other Fergus church building.

The congregation packed the church for the morning service on May 13. While Rev. MacVicar delivered his sermon, titled “Work Out Your Own Salvation,” Rev. Robert Johnston of London led the overflow service, held next door in the Town Hall. With extra hymns, announcements, and a lengthy sermon, the service lasted two hours.

Another service followed at 3pm. Dr. J.S. Ross of Dublin Street Methodist in Guelph, delivered the sermon, with two other ministers assisting in the formalities.

All the other protestant churches in Fergus cancelled their evening services, as did several rural churches. More than 1,000 crowded into the building, filling all the pews, extra chairs in the aisles, and floor at the front of the church. Some even stood on the stairways.

Dr. Robert Johnston of London led the service. A giant of a man, his towering height and imposing weight dominated the church. Johnston belonged to the ranks of the old-fashioned religious orators, a vanishing breed even a century ago. He held the crowd spellbound for his sermon, “Purge me with hyssop and I shall be clean.”

The day ended with a sizeable offering to be applied to the construction account. The building had gone way over the initial budget, but donations had exceeded expectations as well. No one regretted a penny.

The next 25 years rolled along smoothly and pleasantly for Melville Presbyterian.

It is curious that the most controversial Canadian religious event of the 1920s, the union of the Methodist and Presbyterian churches, caused barely a ripple at Melville. The congregation voted on union on Feb. 10, 1925. Of the 393 eligible to vote, 81% cast ballots. The result was a 211-107 margin in favour of union. Some of those who opposed union departed to join St. Andrew’s Presbyterian, which had opted to remain outside the union.

Soon after the vote, Melville invited the Fergus Methodists to join them. The Methodists readily agreed. Their own church was 56 years old, and needed work.

It would be senseless to maintain two United Churches in Fergus, and Melville’s facilities were overwhelmingly superior.

The Methodists continued services on their own until early Mar. 31, 1926. In the meantime, both churches co-operated for an orderly union of the two congregations as Melville United Church.

One of the problems was overcrowding in the Sunday school. The octagonal Sunday school wing on the south side of Melville simply couldn’t cope with the number of youngsters, and for all the activities that the Methodists like to offer during the week.

Melville continued to use the old Methodist church for some of the Sunday School classes.

Among those Methodists who joined Melville were members of the Beatty family. Martha Beatty (or Mrs. George Beatty, as she liked to be called), the matriarch of the family, had been teaching Sunday School for a half century, and she spearheaded efforts for enlarged facilities beginning late in 1926.

Discussions for a new wing lasted three years, and at times became heated. Part of the congregation disapproved of the scale of the plans, and others resented the fact that Martha Beatty’s voice seemed to be the most important one.

Members of the Beatty Bros. firm dominated the building committee, and the Beatty family offered to match the donations given by other people. The committee visited other churches for ideas, and then hired the Toronto architectural firm of Horwood & White, who had designed a church wing that they liked.

Despite the controversy, donations poured in. The congregation approved the plans in March 1930. The budget, at $75,000 was four times the cost of the church, built 30 years earlier. The fact that over $60,000 had already been subscribed undercut the criticism.

Construction of the wing, soon named Melville Hall, required the demolition of the original Sunday school. The new structure was immense: 68 by 82 feet, with more than 5,000 square feet of space on each of three floors, and taking advantage of the slope between the church and the Grand River.

For the Tower Street and Grand River sides, Horwood & White specified the same Inglewood sandstone that had been used for the church. The westside wall, out of sight from the streets, was local limestone, some of which came from the excavation for the basement.

They style was modern, with a flat roof, but it blended well with existing church. Large windows overlooked the Grand River to the south. The Tower Street side featured a gothic doorway, with stained glass windows featuring United Church emblems.

The building committee believed that these were the first United Church emblems anywhere to be done in stained glass.

Schultz Construction of Brantford submitted the low bid, and work began at once. Most of the subcontracts went to out-of-town firms, but J.J. Calder of Fergus secured the electrical work, W. Ebdon & Sons provided the windows, varnishing and painting, and Norman Stafford of Elora received the plastering contract.

The contractors soon encountered problems. The church had attempted to purchase the blacksmith shop to the south of its property, but the owner, a Roman Catholic, disliked Melville Church, and the Beatty family in particular. He would not sell at any price.

The architects placed the south wall of the addition as close to the lot line as possible. During construction, the owner would not allow any material or scaffolding on his property, and consequently, the south wall of the addition had to be built from the inside.

The cornerstone ceremony, on Aug. 4, 1930, duplicated very closely the original one in 1899. Margaret Smellie, who wielded the ceremonial trowel on that occasion, had died long before. Martha Beatty was the obvious choice. She place a copper box in the stone, and tapped it with a ceremonial trowel, just as Margaret Smellie had done 31 years earlier.

Schultz and his subcontractors completed the exterior work before winter, allowing completion of the interior during the first two months of 1931. The work was done in plenty of time for the dedication service on March 8, 1931, though Sunday school classes began using the building a week earlier.

The basement floor contained a gymnasium, two meeting rooms and a kitchen. For a banquet, the gymnasium floor could be filled with tables and chairs for 500. The second floor contained a library, a parlour with a fireplace, and rooms for the Sunday school classes. The third floor contained a large assembly hall with a stage and seating capacity of 600. It could be divided into classrooms with moveable partitions.

With close to 500 enrolled in the Melville Sunday school, the addition was a lively place on the Sabbath.

The church intended the hall to be used for community events as well. It filled a much-needed void in the public facilities of Fergus. Melville Hall assured Melville Church the leading place among the churches of Fergus, and it cemented the Beatty family as the dominant force within the church, a role they would retain for the next quarter century.

The old Fergus drill shed, later known as the Town Hall, stood immediately to the west of Melville Church. Constructed in 1868, its basic proportions resembled the drill shed in Elora, now occupied by Elora’s liquor store. The Fergus structure passed to the hands of the municipality early in the 20th century, and for several decades was used for theatrical productions, political meetings, and dances.

In 1951, faced with major repair bills, the Town of Fergus sold the building to F.G. Clark, and six years later it was purchased on behalf of Melville Church for $5,200.

The church rented the building for use as a warehouse.

In the 1960s there were rumours that a supermarket would lease the building, but in 1969 the church announced that it wanted to demolish the old Town Hall for additional parking space.

Almost immediately, the church changed its mind, but in 1975 the parking lot proposal came up again. The result was an eight-year controversy that split the congregation and caused much ill will amongst Fergus residents.

One group of citizens wanted the building to be used as a seniors centre. The group soon had a $40,000 commitment from the Rotary Club, plus additional pledges. The church itself swung back and forth in its intentions. The Town of Fergus offered to buy back the building in 1980, but the church voted down the offer.

At that point, three of the trustees resigned, and a number of families left the church over the issue.

In 1983, Fergus council designated the building under the Heritage Act, and took steps to expropriate. Later in the year, council changed its opinion, and, by a 4-3 vote, opted to build the Seniors Centre in Victoria Park.

The issue of the Melville parking lot stirred much interest outside Fergus. There were stories in the Toronto dailies, and in Maclean’s Magazine. Despite the designation, the Melville trustees voted by a 32-4 margin to proceed with demolition, which they were entitled to do after six months’ notice.

The preservationists secured injunctions to stop the wrecker’s ball, but these only bought a few weeks of reprieve. A demolition firm reduced the old Town Hall to rubble on the morning of Dec. 15, 1983.

The loss of the building left many in Fergus embittered, and gave Fergus a reputation of being hostile to its own heritage that took years to shake off.

Seventeen years later, the controversy had receded into memory when Melville United Church celebrated the 100th anniversary of the building. After more than a century, it is still one of the jewels of downtown Fergus.

*This column was originally published in the Wellington Advertiser on Feb. 7, 2003.