The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

Note: This is the first column of a three-part series about Melville Church in Fergus.

Though it is not fashionable to do so, I emphatically proclaim that a knowledge of church history is a vital key to gain understanding of the development of rural Ontario in all its dimensions.

For us in Wellington County, the Presbyterian and Methodist faiths predominated. The Presbyterians are particularly important: most of the social and political leaders belonged to this denomination, and the divisions with the Presbyterian Church itself had broader implications for the development of our local communities.

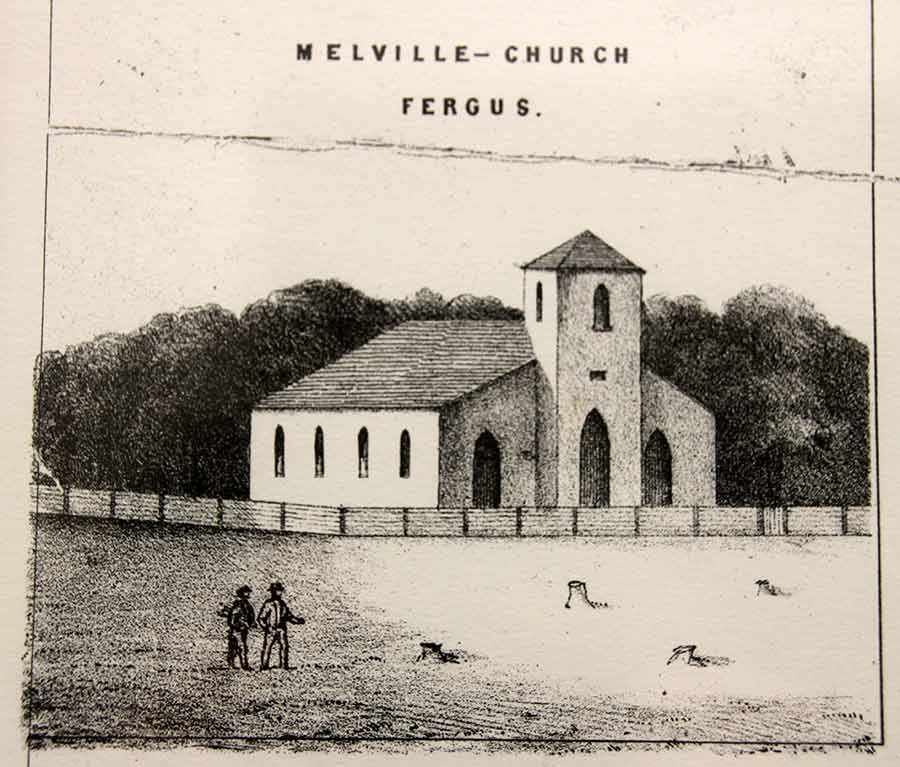

Outside Guelph, the Melville Presbyterian Church of Fergus was perhaps the most important in the county, but before looking at its history it is best to backtrack a little.

The Restoration of 1690 reinstated the Church of Scotland as the established church, enjoying public patronage, in Scotland. A rift appeared in the 18th century because many Presbyterians resented any outside involvement, such as dictation in the selection of ministers, in their own congregations.

The Secession Church resulted. This was a splinter group that rejected all associations with a state church, and various factions soon emerged within the Secessionist movement as well.

Naturally, those divisions came to Canada with the Scottish settlers. In Fergus, for example, St. Andrew’s Church was associated with the Church of Scotland. Nichol’s Bon Accord church, antecedent of Knox in Elora, adhered to Secessionist ideas. As a general rule, Church of Scotland supporters tended to be wealthier and more established. Skilled tradesmen and merchants dominated the Secessionist ranks.

St. Andrew’s was the first church established north of Guelph. The cornerstone of the building went into place in November 1834, little more than a year after the founding of the town. The congregation relied on itinerant ministers until the arrival of Rev. Alex Gardiner in February 1837. The roll swelled under his leadership, but Gardiner died prematurely in December 1841. The elders could find no replacement for two years. The new man, inducted on Dec. 13, 1843, would have a major impact on the community over the following half century.

Rev. George Smellie arrived just as another division gripped the Church of Scotland, and over the same basic issues as previously. At 32, he was ambitious, intelligent, and a man of unshakeable opinions. The unrest had travelled from Scotland to Canada, and Smellie did nothing to hide his sympathy with the dissidents.

Trouble in Scotland reached a climax in 1843 when Rev. Thomas Chalmers led about a third of the ministers out of a meeting, and took steps to establish a new body, which quickly was named the Free Church of Scotland.

In response, Canada’s Presbyterian ministers and leaders met at Kingston in 1844, shortly after George Smellie took the Fergus pulpit. Naturally, he was a delegate. He returned to Fergus full of enthusiasm for the new movement. The session of St. Andrew’s met on his return, and Smellie persuaded most of the congregation to leave the Church of Scotland and join the new body.

A few diehards did not support Smellie. Their leader was A.D. Fordyce, himself a powerful social and economic force in the young community. Fordyce threatened Smellie with a lawsuit if he persisted. St. Andrew’s was built for the Church of Scotland, he declared, and it would always be the Church of Scotland.

Furious with the ultimatum, which ran counter to the wishes of a majority of the congregation, Smellie led a walkout. St. Andrew’s had 449 members at the time. Of these, 360 followed Smellie. Their ranks included all the elders except Fordyce.

With his supporters, Fordyce staked a claim to the church. When he heard that some of the dissidents planned to take over the building, he posted a guard there. For several months, armed men slept in the church to hold it for the Church of Scotland, while others protected it during the day.

The dispute continued for the rest of 1844, and into 1845. Rev. Smellie conducted services in the school house, while the much-reduced ranks of St. Andrew’s gathered at the church each Sunday to hear Fordyce himself conduct the service.

Eventually, in the summer of 1845, Adam Ferguson intervened. He was the cofounder of the settlement, and the disputed church was receiving widespread publicity and detracting from the sale of his land and Fergus lots. Ferguson donated a lot for a new church, a 10-acre plot for a manse, and a sizeable donation of $200 to open a building fund.

Until a new church could be built, he insisted that the rival groups share the existing church, with Fordyce conducting the Church of Scotland ritual at 10am, and George Smellie preaching his Free Church service an hour later.

Ferguson’s prestige helped secure the compromise. He also was a neutral arbitrator: Ferguson was an Anglican, not a Presbyterian. But his true clout was an economic one: most of those involved in the dispute, on both sides, owed him money.

Shared use of St. Andrew’s Church did not last long. By the end of September, Smellie and his Free Church followers met in borrowed quarters. The dispute had degenerated into personal spite between Smellie and a few individuals in the Church of Scotland faction.

George Smellie and his followers met on Oct. 13, 1845 to plan the construction of a church and set up a building committee. They decided at this meeting to name the church after Andrew Melville, the 16th century Presbyterian leader who championed the cause of the independence of the church.

The lot provided by Ferguson for the new church was on the south side of the river, immediately to the west of the present tennis courts. Ferguson’s original plan for Fergus had a square located on this property, connected to a second square, on the north side of the river, by Tower Street. St. Andrew’s Church already faced onto the upper square.

In 1845, Ferguson still entertained hopes of making Tower Street into the main commercial thoroughfare of the town. He now had a Presbyterian Church to anchor each end of it. This was a clever way of turning trouble into a marketable asset, but in the long run, Tower Street never became the main shopping street.

Following some site preparation work in the fall of 1845, the main work on the new church was completed during 1846. Local contractors Alex Munro and Andrew Burns took on the carpentry. The partnership of Bill Sandy and John Bayne secured the masonry contract. The church was built of stone, with seating for 400. The contracts included construction of the manse, and totalled $3,200.

Melville Presbyterian Church opened on March 4, 1847. Dr. Burns, a cleric from Toronto, preached the guest sermons. The building overflowed with visitors from throughout the area. George Smellie preached the first regular service the following Sunday, March 7.

It was evident at the first service that the building was too small for the rapidly expanding congregation. The principles of the Free Presbyterians, emphasizing local control and democracy, and shunning entrenched wealth and power, resonated strongly with independent farmers and tradesmen. These ideas paralleled the political principles of the Clear Grit wing of the Liberal Party, which was, in the late 1840s, sweeping the countryside of Wellington County and the newer areas of the province.

George Smellie responded by adding extra services each Sunday. The pressure on seating eased somewhat in 1853, when about 60 members from Elora left Melville to form Chalmers Church in the neighbouring village.

Two more groups later left Melville to form new congregations: St. Johns in Belwood, and Zion Presbyterian in Cumnock, the latter formed in 1866. All three of these new congregations regarded Melville as the mother church, and they maintained good relations with it, and with Rev. George Smellie in particular.

A fourth Presbyterian group, under Smellie’s leadership, formed at Ennotville. Smellie established a Sunday school at Ennotville, and preached there occasionally, sharing duties with various ministers in the area. These services, therefore, had a nondenominational flavour. The Sunday school survived for almost a century.

Even with a large portion of the Melville congregation in the new churches, pressure for space continued. The addition of wings to the church in 1861 helped a great deal. Other work to the church building included an addition to the square tower in front. These projects cost some $2,700.

By the 1860s, Rev. George Smellie had become a patriarch of Presbyterianism. A large man, he presented an impressive figure in his black robes. He had a manner and dignity to his movements that immediately commanded respect. He made the most of his voice, combining a rich Scottish accent with a deep resonant tone. His delivery held the full attention of an audience for a long as he desired.

The boom in Fergus in the early 1870s, following completion of the railway, swelled Melville’s membership well past the 1,000 mark, making it easily the largest congregation in the county outside Guelph. The session on several occasions discussed a new church to accommodate everyone in better surroundings, but nothing concrete resulted from the talk.

Despite the size of his flock, George Smellie tried to visit the home of every family in the church once each year. Parishioners looked to these visits with a mixture of pride and dread. Smellie’s humourless, dour personality intimidated most people, and children genuinely feared his visits. He was in the habit of quizzing them on their Biblical knowledge. The penetrating glare of his eyes, when the answers failed to meet his expectations, chilled youngsters to the bone.

On the home front, Smellie’s own family presented a textbook example of the cobbler’s children going barefoot. His offspring ran wild, and were the worst mischief makers in the village of Fergus.

Margaret Smellie, George’s wife, was no homebody. She worked at least as hard as he did for Melville Church. Margaret organized Bible classes and Sunday school activities, and busied herself with various church organizations.

George Smellie never gave a moment’s consideration to leaving Melville. The church was largely his own creation, and he treated it as his personal domain. Ill health forced him to step down in 1888, after 43 years in the pulpit of Melville Presbyterian Church, plus another two as the incumbent of St. Andrews and as leader of the dissident Fergus Presbyterians.

Smellie’s successor, Rev. R.M. Craig, served from 1888 until ill health forced his resignation in 1895. Craig’s successor, Rev. John McVicar, restored the vigour that the church had enjoyed under Smellie in his prime.

McVicar pushed ahead with a dream that Smellie never realized: a new and larger church. He persuaded the session to form a building committee in November 1898.

Like Moses, Rev. George Smellie did not live to set foot in the promised land. The patriarch of Presbyterianism died in 1896, at the age of 85.

*This column was originally published in the Advertiser on Jan. 24, 2003.