WELLINGTON COUNTY – Wencke Rudi is bringing the county’s Black heritage to life, one pin drop at a time.

The University of Guelph doctoral student spoke of the county’s Black history to around 135 people gathered for an online webinar on Feb. 17 as part of Black Heritage Month and the Guelph Black Heritage Society’s (GBHS) #ChangeStartsNow initiative, providing educational programming on Black heritage and culture throughout February.

Wencke Rudi (still image from webinar)

To think of Black individuals as landless wanderers into Wellington County, disconnected from the land, is to discount their role in the county’s very formation and to render them un-Canadian, Rudi told the webinar’s particpants.

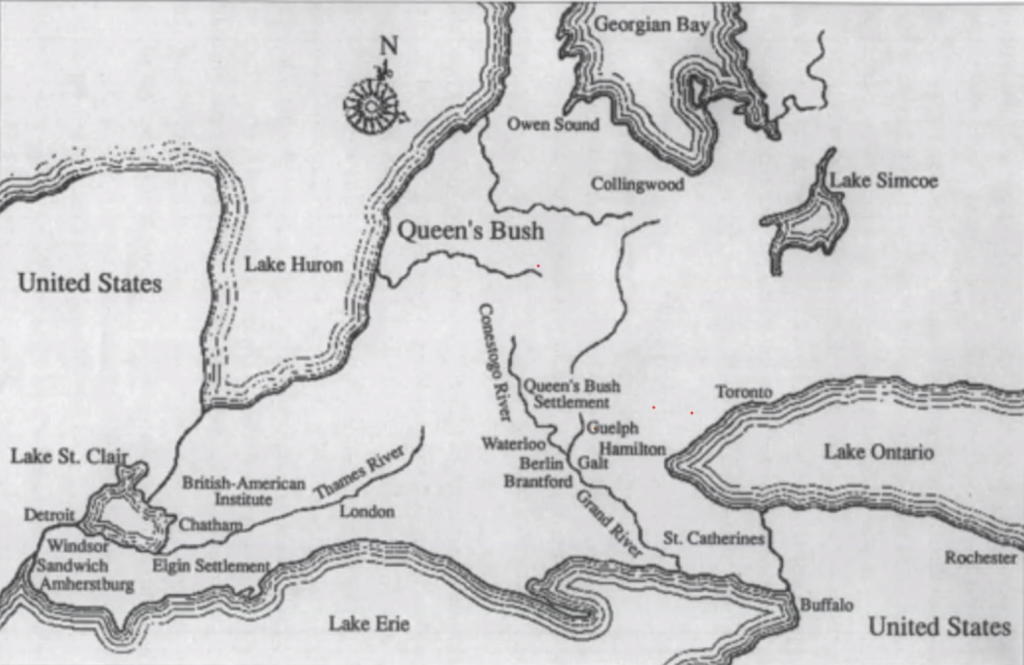

Shifting the historical narrative away from a white-ruled and euro-centric one, Rudi explored the county’s Queen’s Bush settlement, carved out by the hard labour of Black people fleeing slavery and persecution from the United States in the early 1800s.

“The story of Queen’s Bush settlement really starts in the southern states of the United States, where Black enslaved people were moving from Kentucky, up into Ohio,” Rudi explained.

“These Black enslaved people were moving up into Upper Canada through the Underground Railroad, and beginning to come into the sort of more wilderness areas,” she continued.

During the 1820s and ‘30s, what would later become known as Queen’s Bush had no official title or claim on the land.

(submitted image)

The former slaves were met by dense brush, the untamed wilderness of Peel Township (now Mapleton) bordering the hamlet of Wallenstein and Township of Wilmot.

Hardwood trees were axed and small cabins formed with manual labour, and by the next decade, there were 1,500 people said to be living in the settlement.

For much of the area’s history, Rudi relied on the book The Queen’s Bush Settlement: Black Pioneers 1839-1865 authored by Linda Brown-Kubisch.

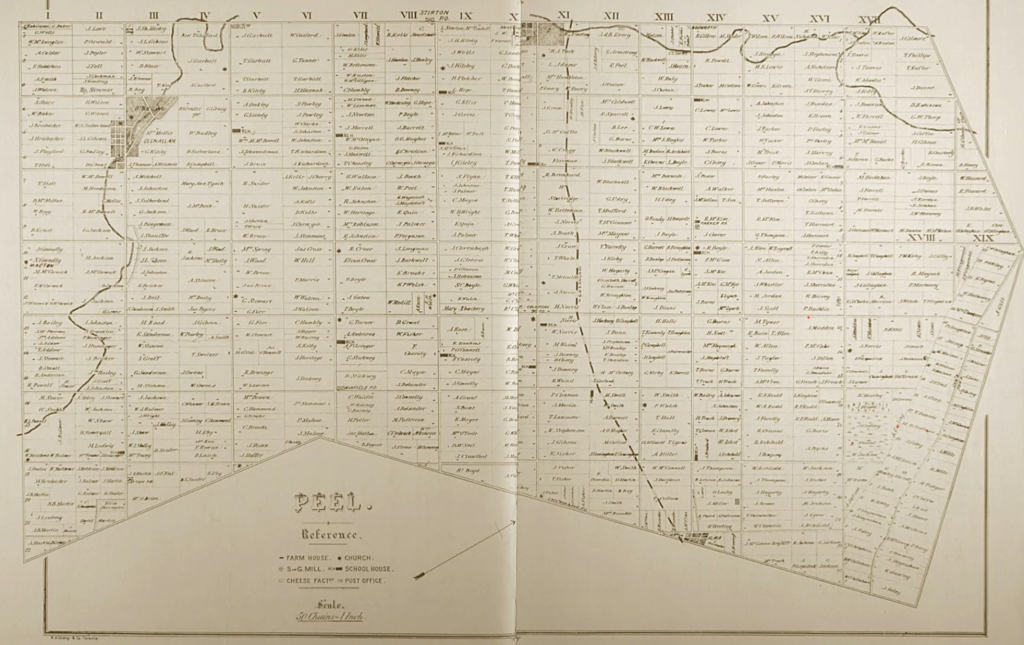

Rudi brought in maps, visuals and recorded archival accounts to form a historical narrative centred around the question: “What happened here?”

In 1845, a land agent came along and noted names, lot locations, land clearings, structures and the amount of crops harvested.

Pointing out an example of an entry on the document, provided by the Wellington County Museum and Archives to the GBHS, Rudi said: “We know that he has a house, a barn and about seven acres cleared.”

Within the rows of information was marked the letter ‘B.’

“It was figured out that these ‘Bs’ were meaning that this was a Black person, the ‘B’ was signifying the Blackness,” Rudi said.

Land information for Peel Township, now Mapleton. (Still image from webinar)

With a starting point established, she began looking at historical township maps from the early 1900s, superimposing the maps over modern Google Maps to try and place where the old settlements were located.

Rudi admitted to an element of guessing, and cautioned that place locations are approximations.

(still image from webinar)

Lacking from the dry land information, Rudi said, was a “sense of impact” or well-being of the community and families. She wanted to frame the settlement within a human context, exploring how people lived and interacted.

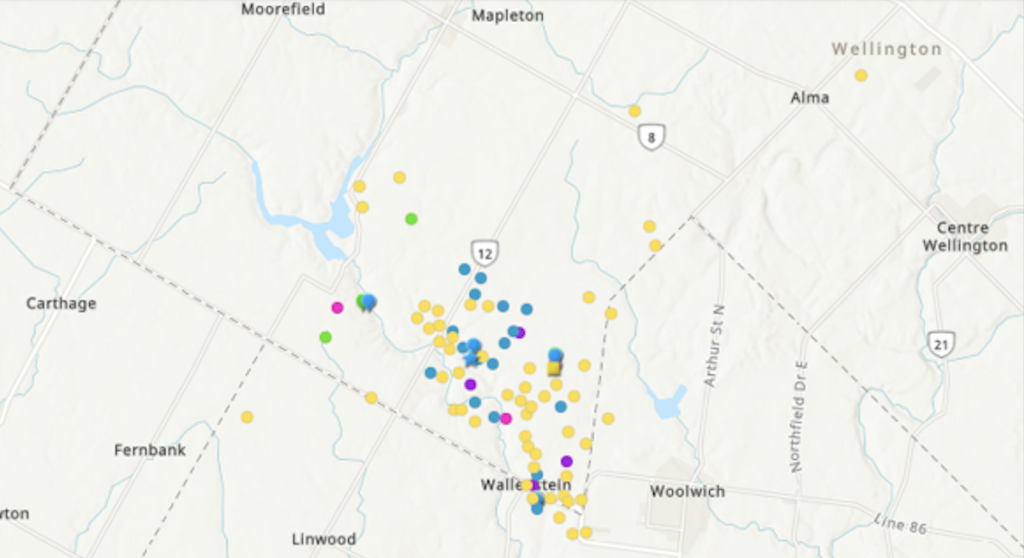

Inputting her plotted data into the online mapping software, ArcGIS, Rudi was able to create a map specifically highlighting and featuring the lives of Black people — a “big moment.”

The mapped dots represented Black individuals, households, families, a school and church. Different colours represent changing time periods.

Blue is the late 1830s and yellow represents the peak of the settlement during 1840-45.

“It also shows how many people there were,” she said.

Rudi pointed out how closely everyone lived together, referencing a group of colour concentrated around the settlement’s Wallenstein border.

The proximity of the dots, she said, helps to provide insight and allow speculation about what life was like in the community.

Dots plotted onto a map represent locations of significance to Wellington County’s Black heritage within the Queen’s Bush settlement. Yellow dots represent the settlement’s peak during 1840-45 and blue dots represent the late 1830s. (Submitted image)

“You can start to imagine: ‘How was the walk to school, how was the walk to church, who was on neighbouring lots, who was helping each other?’” she said.

“We can really see that the history of Queen’s Bush is integral to the history of Wellington County; the [towns] that are there now, they exist because that land has been cleared because of that Black labour … creating these roads, creating these paths,” she said.

In collaboration with GBHS, Rudi is advancing the project into a “driving map” that can be used by residents to explore areas of Black significance within the county. The goal is to have it ready around springtime.

“I think that this is something that is beyond February … beyond this sort of specific time in Black Heritage Month,” Rudi said of the project.

“I think this is coming within sort of this larger wave of efforts of decolonizing, and working with Black heritage and these materials, and trying to reconcile that in terms of what that means with where we currently are in this space.”