WELLINGTON COUNTY – “It’s time for us to work together. It’s time for us to heal. It’s time for us to create the kind of world we want to live in.”

Hope Engel says that is the message behind the Indigenous anthology Mihko Kiskisiwin, or Blood Memory, a collection of poetry, short stories, non-fiction and other art.

Dozens of Indigenous creators from as far as Saskatchewan and the southern U.S. came together to create Mihko Kiskisiwin, but its roots are in Wellington County, going back five decades to 1973 and the creation of Plume Society.

Plume Society

Bay of Quinte Mohawk Elder Karon:tes Stewart is of the Turtle Clan family and lived in Wellington County from 1968 until 2019.

When she was 17, her parents opened their home to First Nations young offenders, and Plume Society was born.

It wasn’t a group home, Stewart said, “just a farm.”

Plume Society offered a place for people to relax, walk the fields, sit by the river and “just create,” Stewart said.

“In our house we didn’t call it art. It was just part of our healing and our expression.”

And the world was their canvas.

River Bundles: An Anthology of Original Peoples in the Waterloo-Wellington Region was published by Plume Society in 2007. Submitted image

“Every wall inside and every wall outside – including the barns; including the drive shed, were our canvas,” Stewart said.

Professional Indigenous artists visited the farm too.

“That’s what Plume Society was. Just learning, just sharing our teachings, sharing who we were … it was children telling their stories,” she said.

Stewart said they had fun sharing their writing at festivals including Hillside and the Eden Mills Writers’ Festival.

Plume Society published River Bundles: An Anthology of Original Peoples in the Waterloo-Wellington Region in 2007.

Indigenous Poets Society

Over time, Plume Society transformed into the Indigenous Poets Society.

Since 2020 the group has met monthly over Zoom for creative circles, co-facilitated by Engel and Kevin Wesaquate and supported by Guelph Spoken Word.

The circles empowered people with community and confidence during COVID-19 lockdowns, reducing isolation and inspiring people to write more, Engel said.

Guelph poet, journalist and writer Mike O’dah Ziibing Ashkewe said the Indigenous Poets Society is “Indigenous poets from all walks of experience and life.”

He said the circles helped him realize, “I can probably do this … this really is a door that I can open if I want to explore it.”

“We heard a lot of great writing on this Zoom thing,” Engel said, so they decided to apply for a Region of Waterloo Upstream Fund grant to publish the anthology.

Mihko Kiskisiwin

Kevin Wesaquate co-facilitates Indigenous Writing Society creative circles and is the cover artist of Mihko Kiskisiwin. The Cree artist and poet also came up with the anthology’s title, which is Cree for Blood Memory. Submitted photo

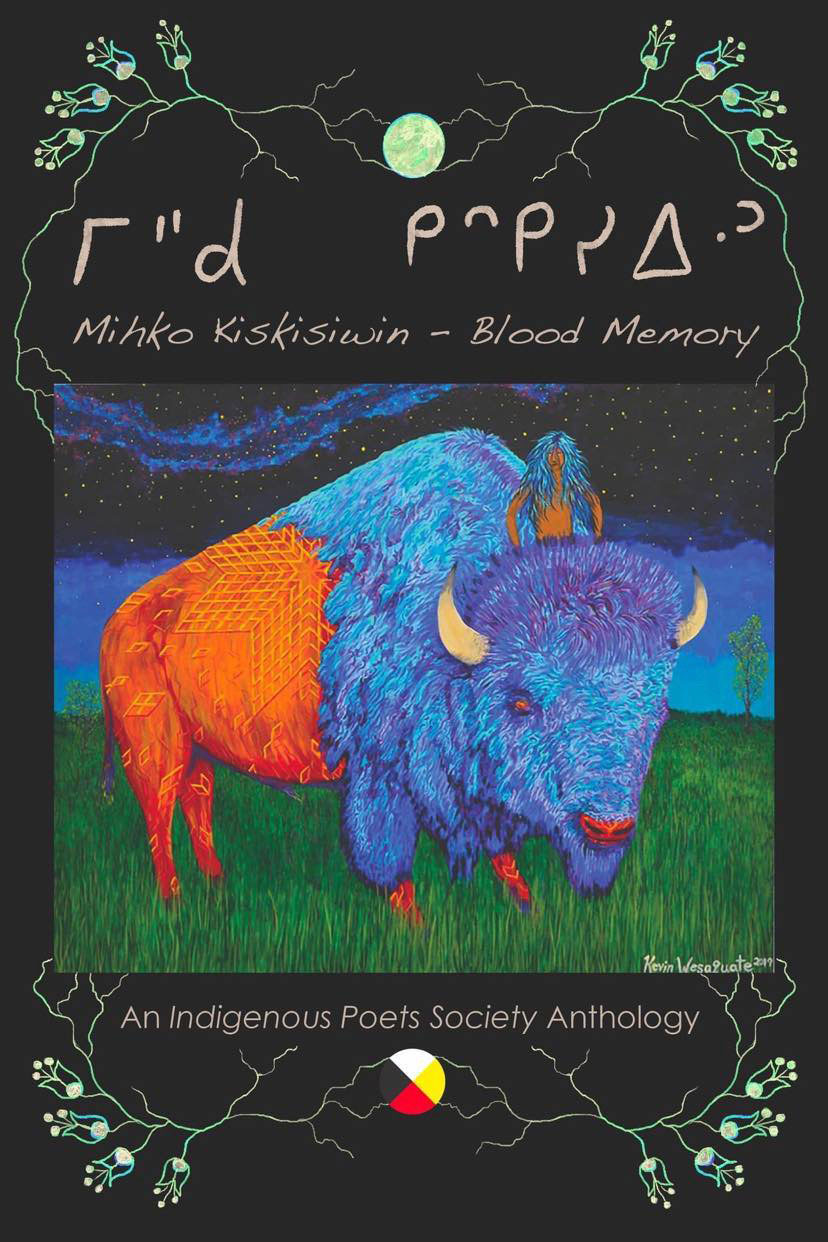

Mihko Kiskisiwin’s cover features art from Wesaquate, a Cree artist, and the title is Cree for Blood Memory.

Though people from many nations came together to create the book, Engel said they chose a Cree title and cover “in the spirit of collaboration and the fact that Cree people have had a great relationship with everybody across the country.”

The book includes a range of writing styles and contributors of all ages and levels of education who have lived both on and off reserve.

There are contemporary takes on traditional Indigenous stories, modern fairy tales, academic pieces, and blackout poetry, Engel said.

Blackout poetry is when redactions are made to an existing written text, creating poetry with the words left visible on the page.

The academic writings include a piece about nuclear energy from a retired judge who worked in the justice system in the southern U.S.

The book’s major themes are identity and community, Engel said.

Ashkewe said when he was asked to contribute, he had recently graduated from the creative writing program at Conestoga College.

At that point, he said, “I never thought I’d be entering the creative writing field.”

Mike O’dah Ziibing Ashkewe’s writing in Mihko Kiskisiwin, or Blood Memory, draws from his experience as a Sixties Scoop survivor and focuses on Indigenous rights. Submitted photo

Ashkewe’s writing in Mihko Kiskisiwin focuses on Indigenous rights and his experience as a Sixties Scoop survivor.

The Sixties Scoop is the removal of tens of thousands of Indigenous children from their families into the Canadian child welfare system.

Ashkewe said his pieces draw from a “primal source of anger” – but not resentment, he assures.

“I’m a big believer in reconciliation, and collaboration rather than retribution,” he said.

“People are starting to realize the truth and reconciliation conversation needs to happen in earnest.”

Increasing understanding

Indigenous anthologies like this one are important because Indigenous voices don’t have enough exposure, Ashkewe noted.

He said Mihko Kiskisiwin “offers an interesting perspective into a world a lot of the population just doesn’t have a lot of experience with.”

“I think a lot of people don’t understand who we are,” Stewart added. “I think a lot of people still stereotype us.

“I grew up watching John Wayne, for example, and all of us portrayed in that were dumb,” Stewart said. “So people carry that, and that’s not who we are.

“We are incredibly creative people. We are kind people. Love and forgiveness is really big in our community.”

Stewart said Engel has done “tremendous work” with Mihko Kiskisiwin and the new anthology is “incredibly healing.”

“These grassroots initiatives are exactly what we need,” she said.

“We live in a world that is starting to have hard discussions about Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, the Sixties Scoop, the Millennial Scoop, and residential schools,” Ashkewe said.

Hope Engel has a primary role with the upcoming anthology Mihko Kiskisiwin, or Blood Memory. Submitted photo

But “before the healing can happen there needs to be truth told,” Engel added.

“So people need to hear about the intergenerational trauma, the boarding schools, the addiction, the mental health and the abuses and the lateral violence and systemic violence.”

The anthology shows “there is more to the Indigenous world than pain and trauma,” Ashkewe noted.

“There is a beautiful creative collective there, we just need the opportunity to show Canada and the world as a whole that there is something really valuable here to contribute to the literary and creative worlds.”

Ashkewe sees a future where Indigenous poets are “put in the same breath as creative and cultural touchstones” such as John McCrae and Robert Frost.

“The possibility is there now for one of these Indigenous voices to come out of the gate and say ‘this is the Indigenous Canadian experience, please, hear my words and consider what they mean and interpret what they mean in your vision of what truth and reconciliation means to you,’” Ashkewe said.

Mihko Kiskisiwin will be available to order from FreisenPress and Amazon in January. Book launches will be planned across Canada, including in Wellington County, Guelph, Waterloo Region, and Saskatoon.

In the meantime, Ashkewe recommends people interested in hearing Indigenous poetry attend Guelph Spoken Word poetry slams or open mics, where Indigenous poets often perform, or connect with Ashkewe directly through his website mikeashkewe.com.