The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

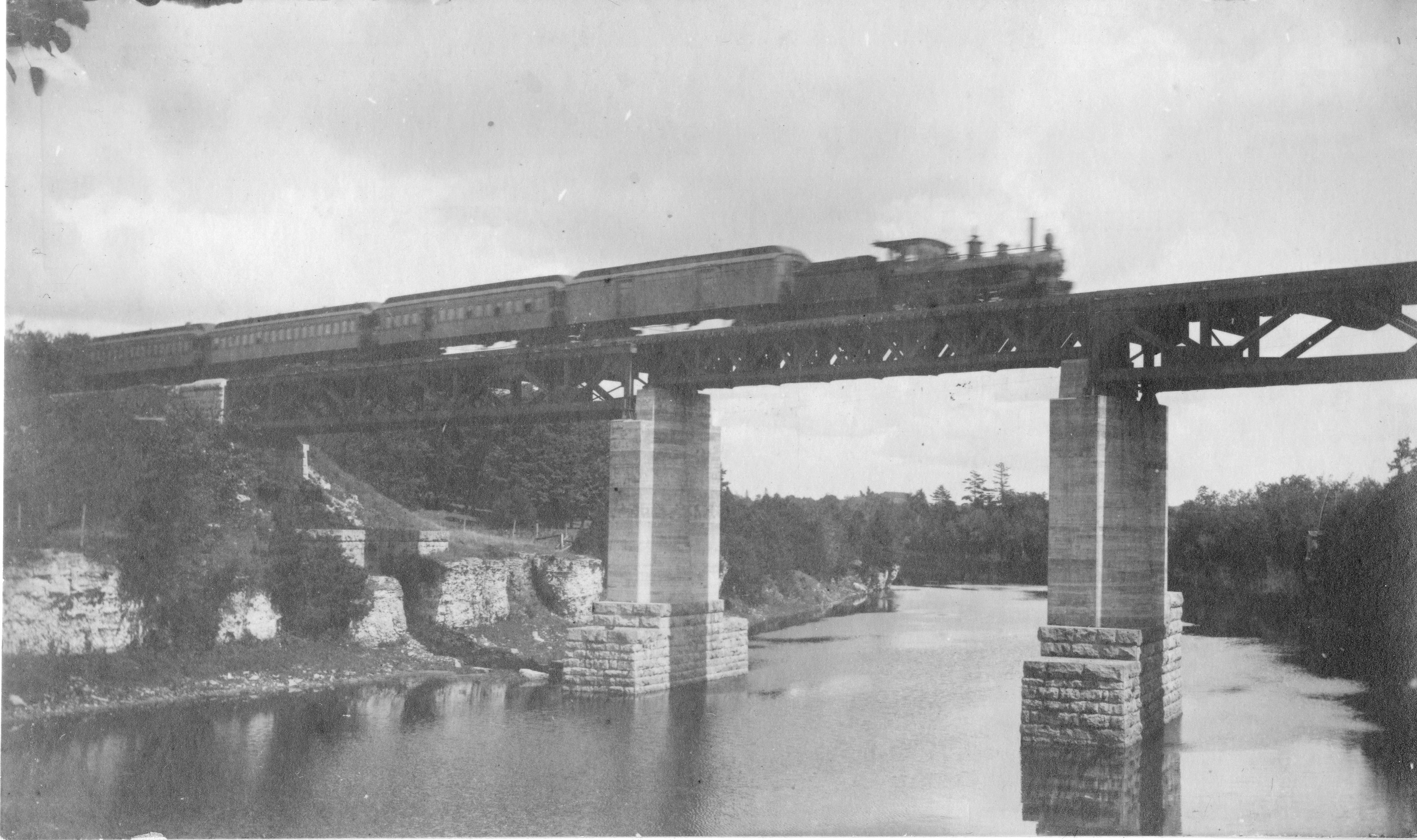

When the new Rails to Trails route between Fergus and Elora opens later this year (1997) on the old Canadian National right of way, the outstanding feature will be the passage over the Grand River on the steel railway bridge.

Constructed in 1909, this is the third bridge built for the railway at this site.

The bridge rests on cut stone piers built for the original bridge. This masonry work, which is still in amazingly good repair, dates to the spring of 1869. This first bridge, built of heavy timber, consisted of five spans.

The Queenston firm of Reekie and Robertson and Reekie secured the contract for the Guelph to Fergus section of the Wellington, Grey and Bruce Railway line in October 1868. This company had fallen into the hands of the Great Western Railway before construction started. The design of the bridge undoubtedly came from the office of George Reid, the Great Western’s chief engineer.

Reekie and Robertson brought in some foremen and supervisors, but much of the work was subcontracted to local men, including the masons who built the piers. The blocks of stone are large and solid, unlike the limestone along the Grand River at this site, which splinters easily. The stone probably came from quarries in the Guelph area. Getting the materials to the site, and to the two piers in the middle of the river, was a feat in itself.

The contractors had the masonry work completed by July of 1869, but the bridge was not completed until the following spring. It was used by contractor’s trains before the beginning of regular service to Fergus on Sept. 13, 1870.

The approaches to the bridge were on timber trestle work, about a half mile in length, and most on the north side, on the approach to Fergus. During the 1870s the railway built up the present embankment by dropping loads of fill from ballast trains.

There was no treated wood in 1869, and railways were lucky if their timber bridges lasted more than a decade. I have not been able to determine when the Great Western replaced the Grand River bridge, but it was likely sometime between 1878 and 1882. At least one photograph of this bridge exists. It looks spidery, though it was entirely adequate for the relatively light trains of the 1880s.

The Great Western system amalgamated with the Grand Trunk in 1882. In some respects this was an unwise decision. The Grand Trunk was saddled heavily with long- term debt, and servicing this debt stained the entire system. As a result, branch lines like the one through Fergus and Elora suffered from deferred maintenance and virtually no capital expenditures until the early 20th century.

Traffic on the local branch increased greatly in the late 1890s. The Grand Trunk had heavier, more powerful locomotives, but the bridges on the branch through Elora and Fergus to Palmerston could not support them. As a consequence, most freight trains and some of the passenger trains required two locomotives. These were the old 4-4-0 type, and some of them were more than 30 years old.

The bridges (over the Grand, the Irvine and the Conestogo) were not the only problems. The track itself was light, and had never been properly ballasted. Wrecks and derailments occurred almost monthly in the years after 1900, and the Grand Trunk had perpetual difficulty in meeting its schedules.

In 1908 the Grand Trunk finally recognized that major work on the line was necessary. During that summer, crews replaced the track between Fergus and Palmerston with heavier rails. The new ones weighed 80 pounds to the yard. The old ones, most dating to 1874, weighed only 56 pounds. Other work included reinforcing the Irvine and Conestogo bridges, and adding extra ballast to the track to improve drainage and prevent frost heaving.

The major bottleneck, the Grand River bridge, waited until the spring of 1909. Even so, the line was improved sufficiently that a faster passenger schedule went into effect in the fall of 1908.

A long work train with more than 50 men arrived in Fergus in late May 1909 to tackle the biggest project on the line. It was a difficult assignment: six passenger trains and at least four freight trains passed over the bridge daily. The new bridge had to be built with no disruption in service.

The construction method used was to build a temporary wooden trestle under the old bridge to support the track, so that the bridge could be replaced in portions. As well, the new bridge involved a change in design. It consisted of three spans instead of five.

The piers at either end were eliminated, and the abutments were moved closer to the river.

Even now, there is still much evidence on the site of the change in design. The original north pier remains beneath the bridge, not far from the new abutment. Some of the stones from the original abutment lie at the bottom of the embankment. There is no doubt about their origin: they have square cut corners, and mortar still adheres to some of them.

With this new design, the end spans are longer and heavier than the centre span, though both have essentially the same design of riveted steel girders. The old bridge rested on iron supports. The new one required raising the piers to the level of the new steel trusses. Rather than cut stone, this work was done with concrete made from portland cement, the wonder building material of the early 20th century.

The end spans were largely complete by mid-July of 1909. It was not feasible to build a temporary wooden bridge between the two piers in the river. A different tactic was used here. On Sunday, July 18 the Grand Trunk closed the line for a day. No regular passenger trains ran on Sunday, but there were usually several freight trains.

All necessary materials and tools had been in place the previous day, but it was still a major task. Cutting out the old span and installing the new one took all day. A large crowd gathered after church to watch the work.

A steady stream of loud profanity from the crew shocked and embarrassed the spectators. Evidently, the foreman decided this was the best way for the men to deal with the pressure of finishing the job in the time available. He refused demands that he instruct the men to hold their tongues.

The combination of Sunday work and profanity inspired at least one sermon the following week.

The swearing may or may not have added to the quality of the work. In any case, the bridge is still solid after standing almost 88 years (110 years in 2019).

The Grand Trunk installed the last of the new rail, between Elora and Marden, in June 1910. The new bridge and track allowed speeds up to 60 miles per hour. Previously, 35 had been considered excessive. New and heavier locomotives began to appear on freight trains.

Hikers and cyclists will soon pass over the bridge in large numbers. They will enjoy a good view up and down the Grand, but they should also look at the bridge itself, explore the areas beside and under it, and remember the men who constructed this fine piece of engineering.

*This column was originally published in the Fergus-Elora News Express on April 23, 1997.