GUELPH – Students carefully weaved orange and white yarn in their school library, making bracelets and bookmarks to raise money to honour Indigenous children who attended residential schools.

The St. James Catholic High School students were preparing for the National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, or Orange Shirt day, on Sept. 30, when they will sell their creations to peers.

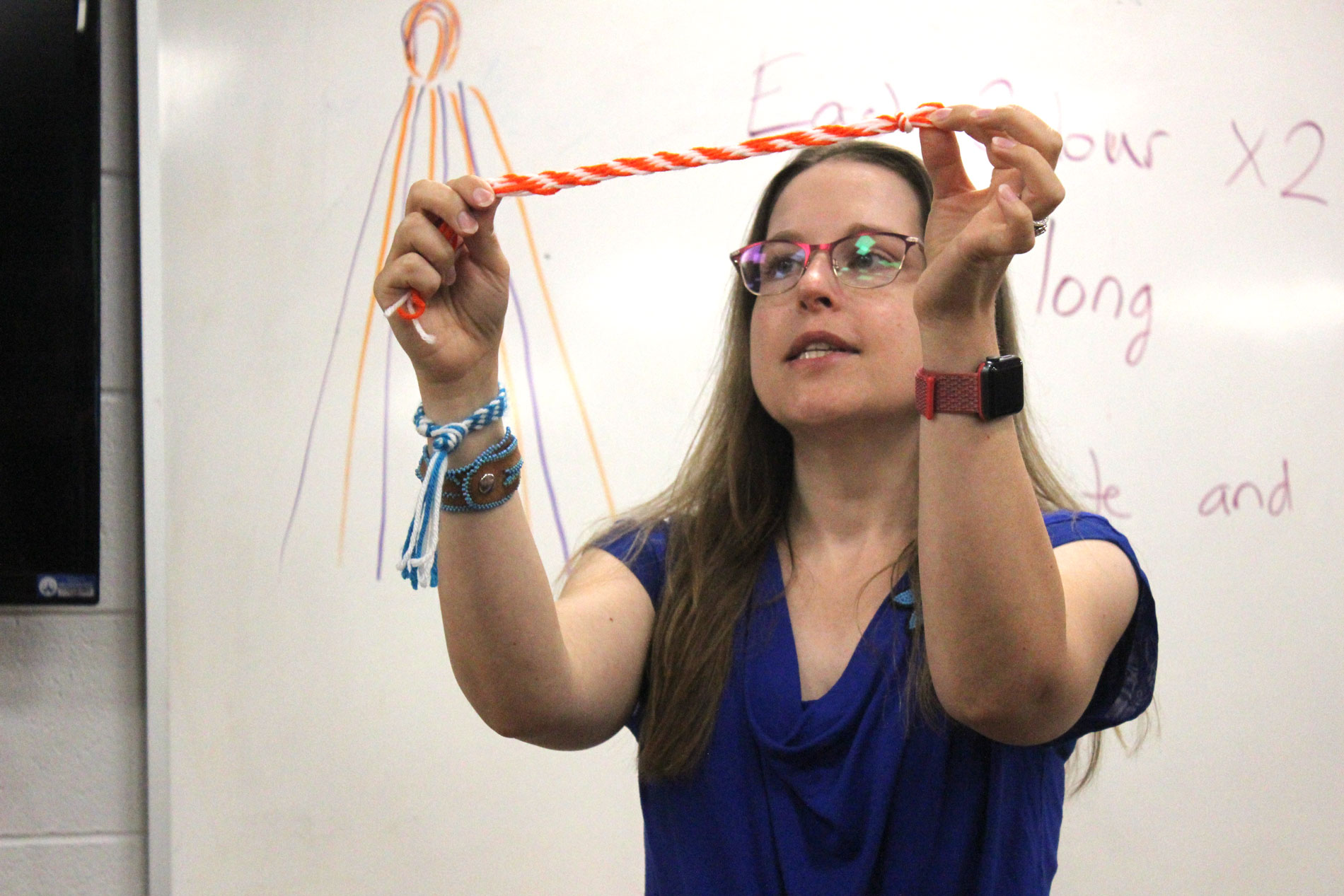

They learned finger weaving, an “old, old skill” that Red River Métis community member Alicia Hamilton said Métis people “learned from our First Nations grandmothers.”

During her visit to the Grade 9 art class on Sept. 18, Hamilton taught the students about Métis history, finger weaving, and the Métis sash.

The finger weaved sash had over 100 documented uses, Hamilton said, and has become a symbol of Métis people.

She taught the students about some of these uses, which Fergus student Lena Appleby enthusiastically recounted to the Advertiser.

Lena Appleby, a Grade 9 St. James Catholic High School student from Fergus, was enthusiastic to share what she learned from Red River Métis community member Alicia Hamilton.

“They can be used for many reasons,” Appleby said, including as bowls, to wrap wounds, and as landmarks to avoid getting lost on a journey.

When worn around the waist the sash supports stomach and back muscles, Hamilton added, and the strong weave meant the sashes could be used as ropes and to carry heavy cargo.

Making a full size sash can take months or years, Appleby noted.

Hamilton taught the students how to make “mini” sashes that could be worn as bracelets or used as bookmarks.

Appleby said learning to finger weave was fun, and “since it’s for Every Child Matters, for Indigenous people, I find joy in it.”

Erin student William MacLean said he enjoyed making the bracelets because “I’m interested in the culture and how things are made.”

He said it feels important to recognize the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation this way because “it helps bring awareness to what happened in the residential schools.”

William MacLean, a Grade 9 St. James Catholic High School student from Erin, said it feels important to recognize National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

“It’s important to recognize the people’s past, and not forget them,” added Fergus student Mikhaela Inoc.

The first mini sash each student made was for them to keep for themselves, Hamilton said. They are set to sell the rest to other St. James students and staff on Sept. 30.

The money raised will go to Geronimo’s Dream, an initiative by residential school survivor Geronimo Henry to build a monument in honour of people who attended residential schools.

Henry lived at the Mohawk Institute Residential School, also known as the “Mush Hole” from when he was five years old until he was 16.

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), more than 150,000 children attended residential schools between 1831 and 1996.

The “explicit intent” of residential schools was to separate First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children from their families and cultures, NCTR officials state.

According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, these schools were “a systematic, government-sponsored attempt to destroy [Indigenous] cultures and languages and to assimilate [Indigenous] people so that they no longer existed as distinct peoples,” something the commission calls “cultural genocide.”

The finger weaving lesson took place during Expressions of First Nations, Métis and Inuit Cultures – a Grade 9 visual arts course.

“We invite Indigenous voices in to share their culture” throughout the course, said teacher Katrina Musselman.

“In preparation for National Day for Truth and Reconciliation we learn about residential schools, survivors, and students that didn’t make it home,” she said.

“It’s our responsibility to make sure our students understand what happened,” she said, “the cultural genocide and forcible removal of children.”

It’s also essential students understand the ongoing impacts of residential schools, she added, including intergenerational trauma. These continued detrimental effects make it a contemporary issue, not just a historical one, she said.

She said it’s important students learn these lessons from “authentic voices,” and form relationships with Indigenous people.

Red River Métis community member Alicia Hamilton, left, said the finger weaving fundraising idea for National Day for Truth and Reconciliation was art teacher Katrina Musselman’s “brain child.”

“These relationships are what’s important to move us forward in a good way,” she said.

Hamilton said Musselman “always finds ways to engage the students” for National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, “to make it theirs, and make it meaningful, rather than just another day.”

At its heart, Hamilton said her finger weaving lesson was “about the students and their efforts for truth and reconciliation.

“It’s a positive movement forward,” she said, and the way the students approach it “is great.”

Seeing the students enthusiastically embrace lessons like this one on finger weaving feels exciting to Hamilton, “because Métis culture had to hide for so long.”

Hamilton said she, her mom and her grandmother were not taught Métis skills such as finger weaving when they were young, as their Métis identities were kept secret.

Teaching young people finger weaving is one way to “keep the culture alive and keep the skills that we have alive,” she said.

For more information about Geronimo’s dream or to make a donation, visit geronimosdream.weebly.com/.