The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

Among the unpleasant occurrences of the eventful year of 1954 were an unusual number of fires.

That year fire destroyed the finishing plant of the Mundell Furniture Company in Elora and the Thompson implement dealership fire in Mount Forest. As well, some major barn fires and several houses are on the list.

In the latter part of the year, the big blaze was the one at St. Stanislaus Novitiate, the Jesuit college in Guelph Township at the northern edge of the city, to the west of Highway 6.

The glow on the horizon could be seen as far as Fergus and Elora.

Compared to other Roman Catholic institutions in Wellington, St. Stanislaus Novitiate was a relative newcomer. In 1913 the College of Saint Marie in Montreal purchased 280 acres of land, known locally as the Bedford farm, and turned it over to the Jesuit Order.

The order quickly set up a novitiate, to provide first- and second-year training for priests, with an accompanying farm, which would be worked by both the novices and by Jesuit brothers. St. Stanislaus opened with eight priests and five novices in residence.

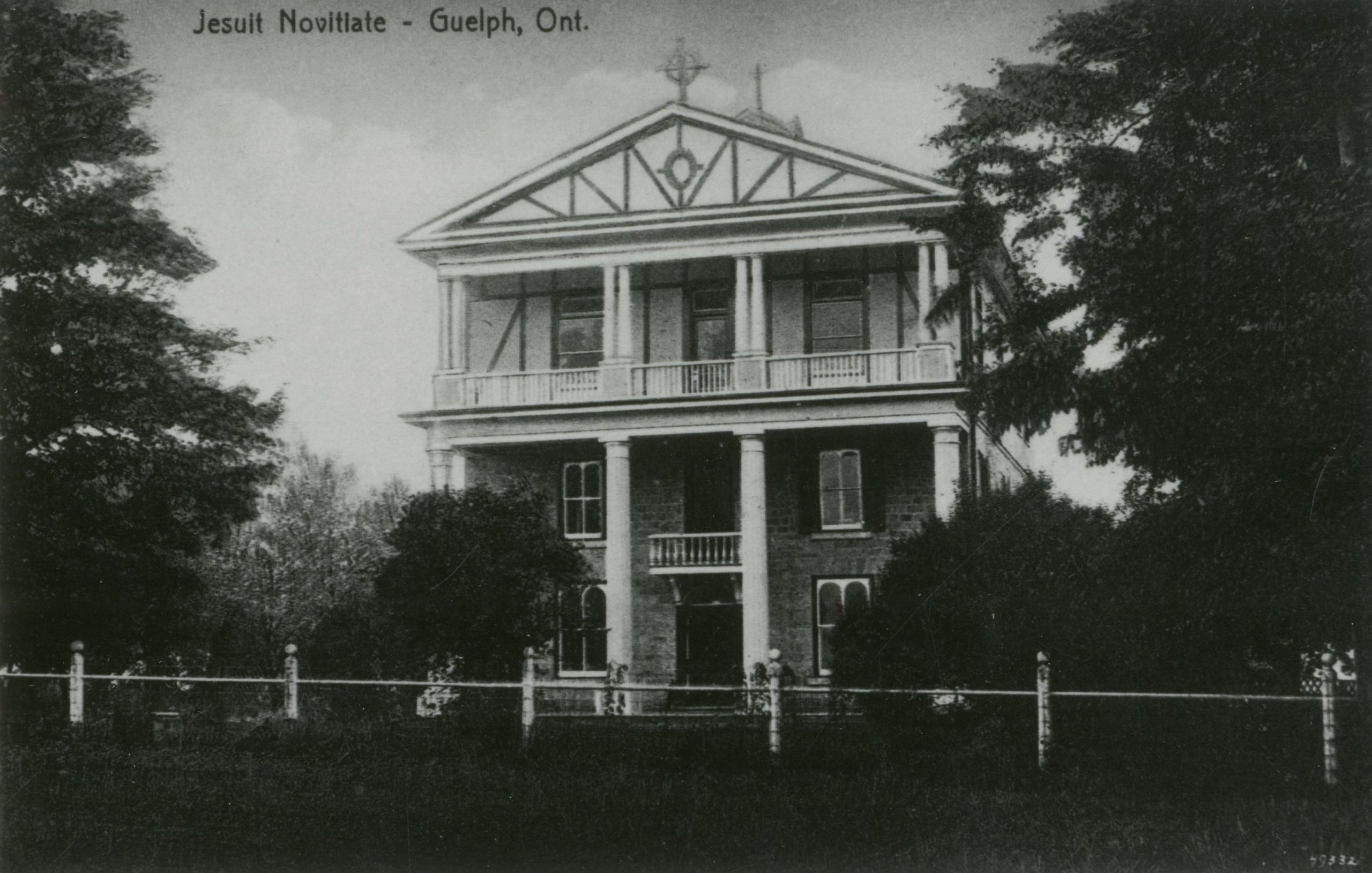

A renovated two-storey stone farmhouse provided the core to what eventually became a rambling complex of wings, additions and a chapel. The Jesuits retained the big porch and the pillars on the front facade; it already looked like an institutional building when they took over. A major addition to the complex opened in 1934. Eventually the college became home to a population of 80 to 100 priests, novices and lay brothers.

At about 6:30pm on Nov. 18, 1954, the fire alarm startled some 85 priests and novices who were eating their evening meal in the refractory. They proceeded outside in an orderly manner. The fire by then was already making rapid progress in the rear portion of the building, which was of wood construction covered with stucco.

Like most older institutional buildings of that period, the novitiate had no sprinkler system, and apparently, no fire fighting equipment of any sort other than the alarm. Assistance was slow to arrive. Guelph Township had no fire fighting equipment of its own, but it did have an agreement with the City of Guelph to provide a pumper truck when an alarm was turned in.

A solitary Guelph pumper eventually speeded up the long driveway at about 7pm, a half hour after the alarm had been turned in. It took a while longer until the pumping equipment was working.

The only sufficient source of water was at the bottom of the hill, in the pond straddled by Highway 6. Due to the distance and height of the novitiate above the pond, only a feeble stream discharged from the end of the hose.

By then it was too late to make much difference. Flames had proceeded from the rear of the building into the original portion. A second Guelph pumper augmented the first at about 10pm. During the intervening time, no call for additional equipment had been sent to either Fergus or Elora, or to Kitchener, which had more powerful equipment that might have made a difference had it been deployed in time.

A new building on the property, separated from the older complex, had a pumping system. It worked, but the volume of water it could supply proved totally inadequate to extinguish the blaze.

Fortunately, a south wind blew the smoke and flames away from the new structure. Had there been a strong breeze from the north or west, the new building would have been doomed as well.

A further difficulty for the firefighters on the scene was the multitude of spectators. Those who arrived early helped the Jesuits retrieve valuables from the building, but as the crowd grew, they were only in the way. People swarmed all over the grounds.

A near disaster occurred when the largest of four chimneys, almost a hundred feet in height, came crashing to the ground, narrowly missing a group of rubber-necking bystanders.

The glow and flames, visible for miles due to the placement of the college on top of a hill, drew more and more people all evening. Traffic on both Highways 6 and 7 jammed to a standstill, as motorists abandoned their cars to get a better look. People came from all directions, but particularly from the north, attracted by the orange glow on the horizon.

By 11pm most of the damage had been done. The rear portion of the complex, built mostly of wood, had been reduced to a bed of smouldering and smoking ashes. The older front portion displayed only its stone walls, a ghostly reminder of what had been there five hours earlier.

The glowing coals reflected eerily from the two remaining brick chimneys, as the shadows of spectators and firefighters moved about. Overall, it was a frightening scene of Biblical power and intensity.

Men from the fire marshal’s office swarmed over the scene the next morning, poking around as the embers flared up occasionally.

As best as they could determine, the fire started with an overloaded circuit in the carpentry shop, located in the basement at the rear of the complex. Estimates of the loss varied between $100,000 and $200,000. The Jesuits managed to save the most valuable of their furnishings and possessions.

Before the fire marshal left the scene the recriminations started. Without its own fire fighting force, Guelph Township depended totally on an agreement with the city of Guelph. Negotiations frequently were protracted and difficult.

City authorities claimed they had complied to the letter of the existing agreement by providing a single pumper for the novitiate fire. Jesuit officials at the novitiate, furious at the loss of the building, blamed bungling by Guelph fire department and by city and township officials, who argued while the fire progressed.

Most of the townships in Wellington had agreements with nearby urban fire departments. For example, Elora covered all of Nichol and most of Pilkington; Fergus a large portion of West Garafraxa. Earlier in 1954 the fire chiefs had hammered out the county’s first mutual aid system. But it was crude, and would require years of refinement before it worked smoothly and quickly.

Insurance covered only a portion of the loss, but the Jesuits quickly came to a decision to rebuild, and on a larger scale than the old structure. In 1954 there was still a strong interest in holy vows by young Catholics, and the Jesuit Order expected that the enrolment of novices would grow in coming years.

The new structure, opened in 1955, consisted of an “L” shaped multi-storey brick building. In 1958 the Jesuits incorporated the institution as Ignatius College. Two years later, Bishop J.F. Ryan opened a $750,000 addition. It was financed by special donations given by 26,000 people across Canada. The new construction added two wings, enclosing a central court.

In 1964 the Loyola Retreat House moved from Oakville to the property, which had expanded to about 600 acres through additional land purchases. The move signified a shift in the use of the property, as interest in the priesthood waned in the late 1960s.

Ignatius College discontinued its classical courses in 1967. Novices studied that material at the University of Guelph. In 1973 most of the novice training was centralized at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington.

Today, some of the property is farmed, but it is best known for the Ignatius Jesuit Centre of Guelph, a very successful spiritual retreat. The 1955 college building provides rental income from a variety of tenants.

The bungled firefighting effort at the 1954 novitiate conflagration resulted in efforts to design a more effective mutual aid system, and better and clearer agreements for firefighting services between the townships and the urban fire departments.

*This column was originally published in the Advertiser on Nov. 12, 2004.