CENTRE WELLINGTON – On Oct. 20 at the Wellington County Museum and Archives, Bob Foster shared stories about his father’s journey as a soldier during the Second World War.

Verdon Stuart Foster was a well-known veterinarian in Fergus. He often went by Stu Foster or Dr. V.S. Foster.

His story begins in Saskatchewan, where he lived on a farm with his mother, father and brother.

In 1926, when the boys were only six and four, their dad died, leaving their widowed mother to continue with the farm duties.

“My grandma continued to farm on her own, which as a woman was extraordinary at that time,” Bob Foster told the Advertiser.

The boys grew older, tending to the farm and helping their mother through The Great Depression.

Verdon finished high school in 1939 and decided he wanted to become a veterinarian. And because Guelph had the only school at which to study veterinarian medicine at that time, he applied there.

Enlistment

The Second World War began on Sept. 1, 1939, and by the time Verdon was 22 the threat of Nazi Germany became much more serious.

After three semesters studying at the Ontario Veterinary College, Verdon joined the army on Feb. 18, 1943.

He and his brother, like many Canadians, volunteered to serve.

“Casualties were high [and] it appeared Germany was winning the war at that time,” Bob noted.

Verdon began his journey in Regina, Saskatchewan, where he received basic military training. He finished training in July of 1943 and got leave to return home to help his mother with the harvest.

“Because food was in short supply and the harvest had to happen; the army recognized that,” Bob explained.

Verdon was only allowed four weeks at his mother’s farm before returning to training in Shilo, Manitoba. He arrived in October and was taught how to handle different types of guns and he completed other intermediate military training.

Verdon then got back onto a train and travelled to Debert, Nova Scotia for more training. The base there also served as the final staging area for troops embarking from Halifax.

A wartime photo of Verdon Stuart Foster.

Heading overseas

Verdon stayed in Debert between January and March of 1944 before departing for Europe. He arrived in England on March 15 at one of the various military “headquarters,” said Bob.

From March to May Verdon was in England training and waiting to fight. The soldiers were days away from the Normandy landings on D-Day (June 6, 1944).

“Just before my dad was to go on the D-Day assault [commanding officers] realized they didn’t have enough infantry signalmen,” said Bob, noting they needed more people trained in the operation of radios, two-way radios and communications.

Officers asked if any soldiers had any science training, so Verdon stepped forward and explained his experience in school.

“He was held back from the D-Day assault in order to take this technical signals training,” said Bob.

“Because dad had a high school diploma and three semesters of training it probably saved his life.”

Verdon learned how to use communications equipment from September to November of 1944, as soldiers were liberating parts of Europe.

Operation Veritable

He then got sent to Ostend, Belgium on Dec. 31, 1944. Allied soldiers had regained control of the region and were now developing Operation Veritable (Battle of the Reichswald).

The large-scale operation aimed to seize the left bank of the Rhine River, which forms the Swiss-Liechtenstein border and partly the Swiss-Austrian and Swiss-German borders.

“There was a little bit of a lull in January of 1945 to give soldiers a rest after five or six months of fighting,” Bob explained.

“Dad fought in the Rhine campaign … in the region of Germany so now you’re fighting on German soil.”

The operation began on Feb. 8, 1945. Verdon was fighting with a radio on his back and a rife in his hands.

Ultimately, on May 8, 1945, Germany surrendered and fighting in Europe ended.

Between May and August, Verdon was still on duty, guarding prisoners of war, burying the war dead and keeping peace and order in the cities.

“You’ve got pure chaos; cities are in ruin everywhere in Europe,” Bob said.

Returning home

After almost three years of service, Verdon got sent back to Halifax in September of 1945. He returned home to Regina in November and got discharged from the army in December.

Verdon had no physical injuries upon his return, according to his son.

After the war he got accepted into the Ontario Veterinary College, studied for four years and earned his degree in veterinary medicine.

Verdon met his wife in 1947 in Guelph and the pair moved to Fergus, where he would work as a vet from 1950 to 1987.

“I know it [the war] bothered him; you can’t be human if it didn’t bother you,” said Bob. “But he managed to be a veterinarian and get through school and raise a family … he was maybe one of the lucky ones.”

Bob noted his father never used to speak about the war, suppressing his feelings and memories – like countless others – to “get on with life.”

“How am I supposed to remember what my dad wanted to forget?” he asked.

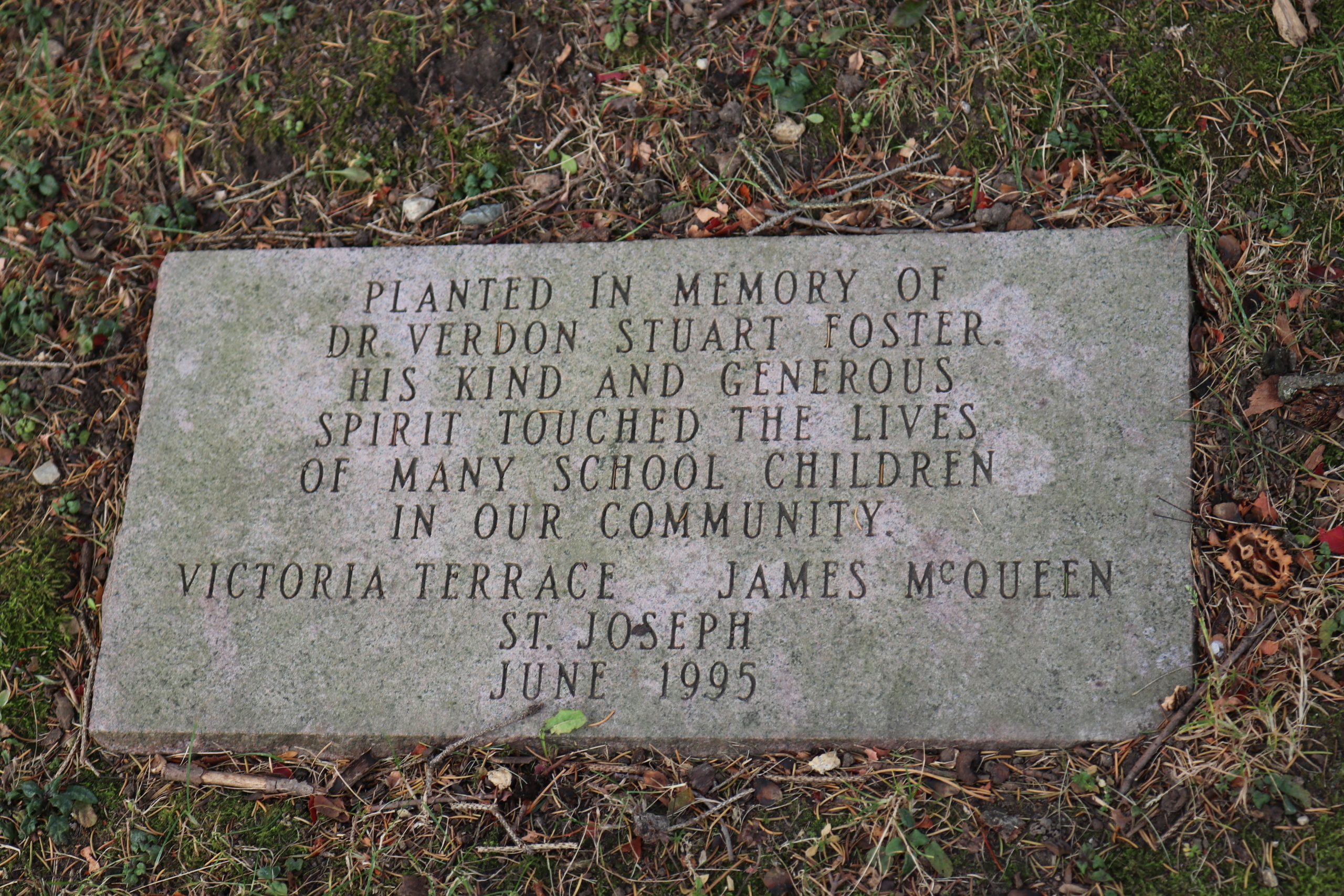

A tree and plaque were placed in honour of Verdon Stuart Foster near the Fergus cenotaph in 1995. The plaque notes Verdon “touched the lives of many school children in [the] community.” Photo by Georgia York

40th anniversary

In 1985, around the time of the 40th anniversary of the Liberation of the Netherlands, a “switch had been flipped” inside of Verdon, his son said.

Verdon and his wife travelled to battlefields in Europe and upon their return, Verdon decided to dedicate his retirement to remembering the past.

He experienced survivor’s guilt about the war, given he had survived and got to live out a “good life.”

“He just kind of unleashed what happened; he wanted people to remember; he wanted my generation [and] your generation to know what happened,” said Bob.

Verdon remained dedicated to remembrance by speaking at schools, organizing dinners, and selling poppies and wreaths.

He was also a Fergus Legion member for 10 years, including two as president.

Verdon Stuart Foster passed away in February of 1995, leaving behind a legacy in Fergus.

Later that year a tree was planted alongside a plaque in his honour near the Fergus cenotaph.

It’s been a “lifelong study” of Bob’s to try to understand what happened to his father during the Second World War.

“If we want to remember, we need to learn our veteran stories so that we can tell the story,” he said.

Bob Foster at the tree and plaque placed in honour of his father, Verdon Stuart Foster, in Fergus on Nov. 1.