WELLINGTON COUNTY – A mild winter means many equine professionals are grappling with how to manage mud.

While squelching through muddy conditions is less than pleasant for horses or their caretakers, the problem goes beyond discomfort.

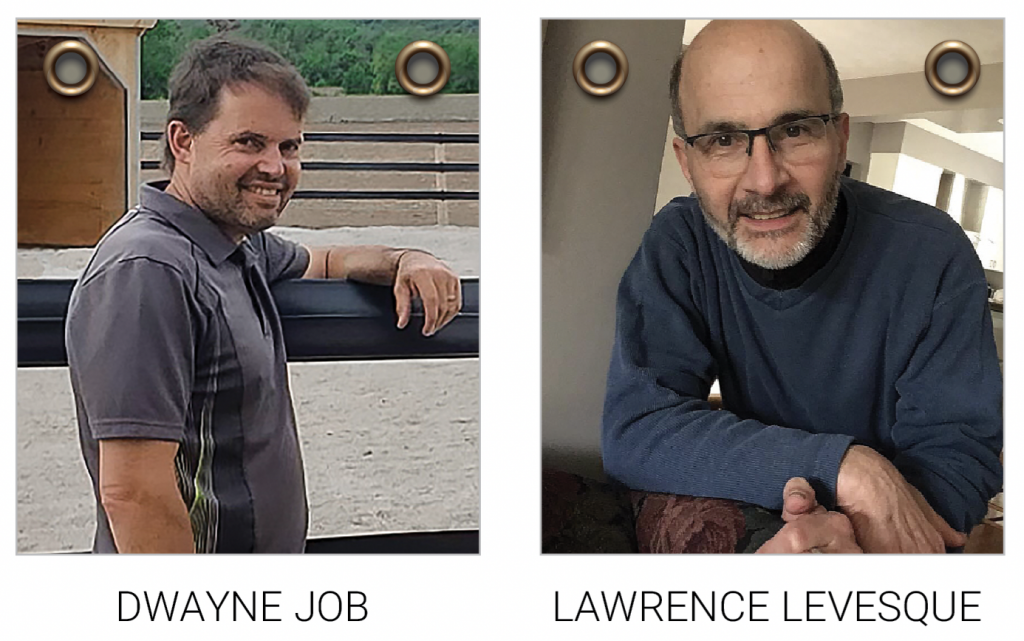

“Animals’ feet being in wet ground for too long can definitely lead to feet problems, including fungus and bacterial infections such as thrush,” said forage and cover crop specialist Lawrence Levesque.

He works at Speare Seeds, a forage and turf seed business based in Harriston.

Hooves create deep ruts in muddy areas, and when the ground freezes this means unsafe conditions for horses.

Horses can twist their legs in the ruts, leading to leg injuries including broken bones, Levesque told the Advertiser.

The best method for managing mud is to be proactive – “it is always easier to avoid creating a muddy condition than it is to fix it,” states a mud management info-sheet from Equine Guelph.

If you’re creating a new paddock, it’s important to consider slope and drainage, Levesque said, as water runoff creates muddy conditions.

But if the paddocks are already established, there are steps that can be taken to manage existing mud, he assures.

Keep horses off the mud

The key is having multiple paddocks and adequate space for the number of animals, Levesque said.

It’s best to keep horses out of the paddock when the ground is soft, to give the ground time to recuperate without hoof-traffic.

When horses step on wet, soft ground, their hooves sink into the mixture of mud, silt and clay, creating a coagulated mess filled with deep hoof prints, said Dwayne Job, president of System Equine, based in Guelph/Eramosa.

Water runs off into ruts made by the horse’s hooves, exacerbating the problem, he added. But there are a few ways to give muddy areas a break from hoof traffic.

Keeping horses inside during the warmest hours of mild winter days helps – so they’re outside while the ground is frozen, and inside once the sunshine softens the ground, Levesque said.

And on mild wet days, it helps to keep the horses inside, he adds. Another option is to fence off the muddiest areas to keep horses away until the ground freezes or dries out.

“Use a temporary electric fence to corner off the area,” Job suggests.

He also recommends flattening out muddy areas with a loader bucket to remove the ruts.

Sacrificial paddocks

Levesque, Job and Equine Guelph all press the importance of having a sacrificial paddock.

It’s a small area you know will get muddy, and do not expect grasses for foraging to grow. Using a sacrificial paddock means primary paddocks can rest during wet conditions.

To maintain the sacrificial paddock, Levesque recommends adding a load or half load of sand to its centre in autumn. The sand will help absorb some of the water.

“The following year, add sawdust or shavings,” he suggests. This creates a mound in the middle of the paddock, causing the water to runoff.

“The surface area will dry quicker and be healthier for your animals,” Levesque said.

And the horses will eventually blend the sand into the soil, he said, and hardy grasses will be able to grow.

Planting seeds

Levesque recommends planting a mix of grasses with long lateral roots that can be self-repairing.

“Not just a forage-type grass but a sod forming pasture grass is ideal – that will be more tolerant.”

A short-growing white clover can be ideal to plant in high-traffic areas of paddocks that are especially prone to mud, he said.

“A lot of horse people don’t like clover because they think it gives their horses too much protein and energy, leading to laminitis,” he noted. But he said most horses will avoid eating the clover, and it is more tolerant to hoof traffic than other plants.

“Give the winter paddock a break in fall to get those roots established,” he said.

Diverting water

Another effective strategy for reducing muddy conditions is diverting water away from paddocks.

“The installation of eavestroughs and downspouts on your barns and run-in shelters will reduce the amount of water entering onto your paddocks,” the info-sheet from Equine Guelph states.

“Downspouts should be directed towards a low lying area outside the paddock” or collected in a rain barrel, it continues.

Surface runoff water can also be diverted by installing berms or French drains. A berm is a mound of soil or gravel that blocks water runoff from entering a certain area, and a French drain is a trench, backfilled with gravel, that intercepts the runoff and directs it elsewhere.

Removing mud, manure; adding sand, gravel

Removing manure from paddocks makes a difference, ideally once a week, or more frequently in high traffic areas, Equine Guelph officials recommend.

And adding sand, gravel or woodchips to high traffic areas can improve footing in muddy conditions.

These footing materials work best when placed on top of landscape filter fabric, Equine Guelph officials state.

Levesque suggests adding enough of these materials to raise the ground by at least six inches, in order to divert the water away.

Job warns that sometimes adding these materials adds to the volume of mud once everything gets mixed in.

“The only way to get rid of the mud is to scrape the organic material off to the subbase,” Job said.

“The lighter brown dirt is usually into subbase material which is more stable,” he noted. “Scrape off all the black dirt,” and then deposit stone dust or screenings to encourage the water to drain off.

Another option is to use a grid system over top of the soil, Job said.

“A grid system is basically a floating pad that the horses can walk on and tractors can drive on.

Grid systems aren’t cheap, he noted, at around $4.24 per square foot, but they’re a “game changer if the mud is really bad.”

In deep mud the grid system will sink down over time, but it can be pulled out with a tractor and placed back on top, he said.

And they can be used in the muddiest areas only, such as around a water trough or gate, instead of throughout entire paddocks.

To read the Equine Guelph info-sheet visit equineguelph.ca.