The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

(Note: This is the second part of a series on 19th century military history in Fergus and Elora.)

Following the burst of activity at the time of the 1837 Rebellion, and a series of reorganizations through the 1840s, local enthusiasm for the volunteer militia declined rapidly, reaching a low point in the late 1850s.

All this changed in 1861, with the outbreak of the American Civil War. The southern states began seceding in December 1860, and full-scale military action started in March 1861.

Many Canadians felt vulnerable to a major American military build up.

Officially, Great Britain remained neutral, but many British leaders had more sympathy for the south: they wanted a supply of cotton, and they feared the northern states were becoming a rival on the world market for industrial goods.

In Elora, Charles Clarke, the storekeeper and radical reform leader, called a meeting for July 20 to form a local militia company. Previously, proponents of local militias had tended to come from the ranks of old order Tories. Clarke represented the opposite end of the political spectrum. Virtually all the men who attended the meeting had no previous experience with the militia.

Clarke told those at the meeting that it was desirable to form a rifle company, “considering the unsettled state of affairs in the neighbouring Republic.” Everyone agreed.

They formed a recruitment committee, accepted the offer of Tom Donaldson, a retired soldier, to conduct biweekly drills, and welcomed the assistance of H.T. Strathmore, who had recently established the Fergus Rifle Company.

Elora’s most hide-bound Tory, Dr. John Finlayson, stated that the company “would dispel the stigma cast upon Elora, on the grounds of its supposed disloyalty, based upon its radical character.”

The remark offended the others deeply. The doctor was forced to withdraw his remarks, and he took no further part in the rifle company.

The Elora Rifles drilled through the fall of 1861, under the leadership of Captain Donaldson. Clarke was named Lieutenant of the company. They spent much time discussing uniforms: what colour and what kind of cloth.

Col. James Webster urged a grey uniform made of Canadian cloth. In December 1861 local tailor John Wilkinson produced a uniform described as “fern brown with red facings, the same as the Victoria Rifles in England.”

The men had to purchase their own uniforms, and therefore believed they should have a voice in the colour and style. They believed their choice was the most inconspicuous colour.

While they were debating uniforms, war hysteria reached a peak over the Trent Affair. The American Navy had stopped a British vessel travelling between Havana and England, and seized two Confederate diplomats. It was a grave violation of the laws of neutrality. Great Britain came very near declaring war, but the Americans released their captives and the situation cooled down in the first days of 1862.

The Trent Affair stimulated enlistments and enthusiasm in Elora. The Rifle Company began to take on a social function as well. In January 1862 the Elora company held a military ball, with visitors from Fergus, Guelph, Mount Forest and Galt. On May 24 the Elora company participated in the Victoria Day parade.

By the end of 1862, though, enthusiasm began to fall off. The dangers did not seem as real, and the regular drills became tedious. The men paraded again on May 24, 1863, but attendance was declining.

The government announced that it would supply the drill sergeants. This offended local sensibilities, and several men resigned. As it turned out, the man sent to Elora proved to be popular. He was Sgt. Ward of the Coldstream Guards, and he worked well with the local officers during 1863.

Ward’s efforts proved insufficient to maintain the vitality of the Elora Rifles. There were few drills or parades by the early months of 1864, and more than half the men had drifted away. Officers rarely showed up for drills and Capt. Donaldson resigned in February. Lt. Charles Clarke succeeded him as commander.

Elora was not alone in having problems with its local militia. The government became alarmed at the general state of unreadiness, and in the summer of 1864 planned a military draft for all unmarried men between 18 and 45. Local men decided to join the Elora Rifles, rather than be drafted to Guelph.

Implementing the draft proved to be difficult. Local assessors were instructed to record the military status of all men during the annual property assessment. The job was generally botched. Elora’s quota was 34 men, and Fergus 36. In the end, there were sufficient volunteers to meet these numbers. The new enlistments boosted the Elora Rifles to renewed vitality.

Fears of an American invasion mounted at the end of 1864. General Sherman stated that it would make sense to take Canada after the south had been subdued, and many in the American Congress held similar views. There were also rumours that the Fenians would attempt some sort of action, or even try to seize Canada to help in their goal of Irish independence.

Alarm increased after the end of the Civil War and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. The American political situation and the economy floundered in instability through 1865 and 1866. Many still wanted to invade Canada. There were fears that discharged, unemployed soldiers would form an alliance with the Fenians. On their own, the Fenians were a motley collection of idealists and barflies, but they could prove to be dangerous if augmented with experienced soldiers.

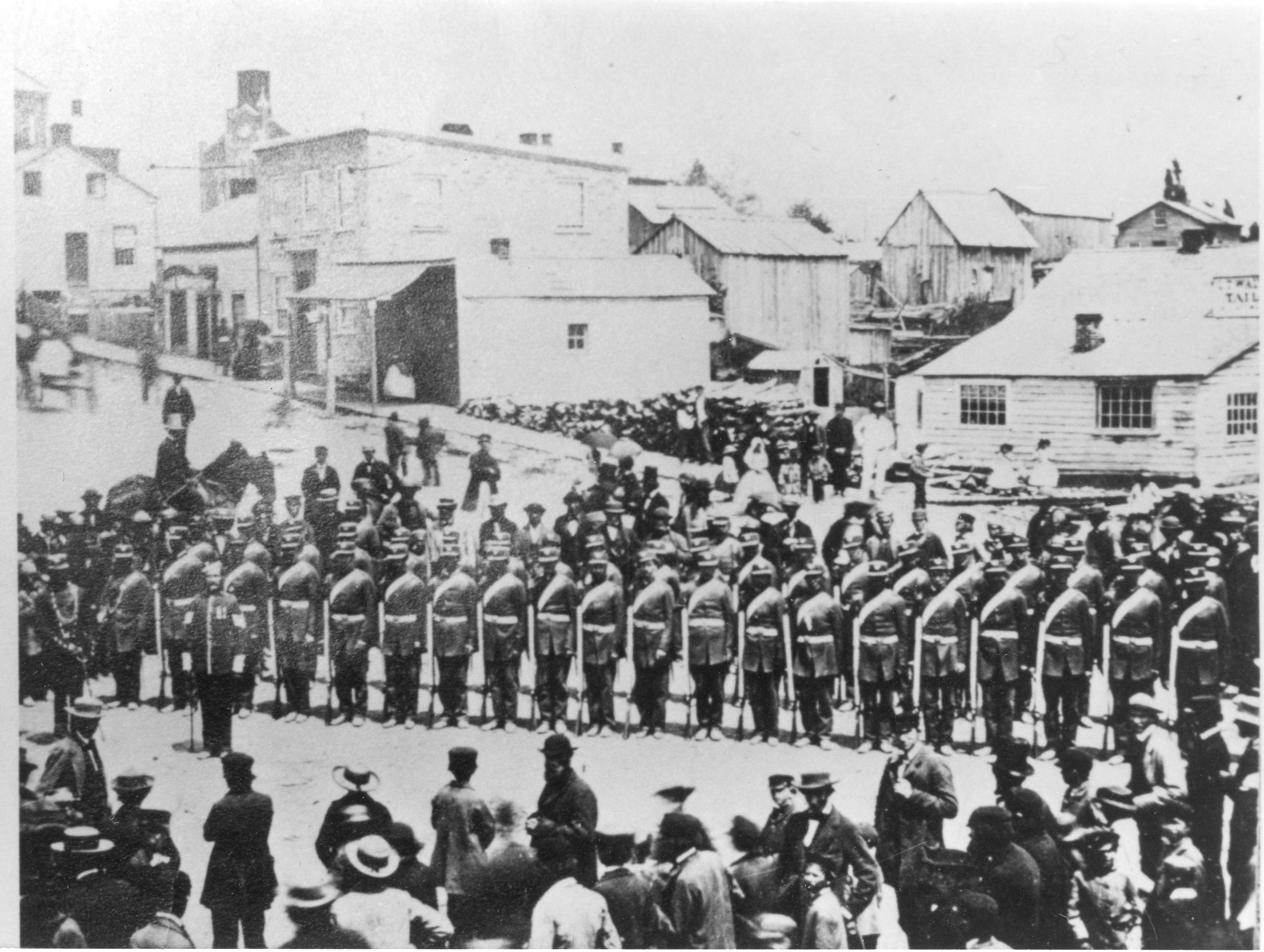

After a series of false rumours, the Elora Rifles were called into action at the beginning of April 1866, to protect against possible border trouble in the Chatham area. Only 55 men were required. Lt. Clarke had to make a selection from a company that numbered more than 80.

Before they left there were many speeches and presentations. On the night after their departure there was an oyster supper in their honour. This was a fundraising affair. The men received only 50 cents per day, less than half their wages at their regular jobs. Elora citizens felt obliged to raise money to help support their families during their absence.

The Elora Rifles spent six weeks at Chatham. No invasion materialized. The company spent its time drilling daily. There was only one casualty: Pte. Carlton dislocated an elbow in a Chatham bar fight.

The Elora Rifles arrived back in Guelph on May 17. Their return offered the only real excitement of the venture. They enjoyed a large meal at a Guelph hotel, then piled in wagons for Elora. They stopped at Hurst’s tavern in Ponsonby for several rounds of drinks, and did not arrive in Elora until after midnight.

Waiting citizens had lit a large bonfire at the edge of the village. The Rifles then marched to the drill shed for a party that lasted until 3 am.

(Next time: Called up again.)

*This column was originally published in the Fergus-Elora News Express on March 25, 1998.