FERGUS – Four years claimed by a flu-like illness steered John Scott on a three-decade trajectory tinkering with ticks.

During the ‘80s, Scott was diagnosed with Lyme disease, a notoriously difficult to diagnose tick-borne disease, causing fevers, headaches and fatigue which can spread throughout the body.

“I didn’t know what was wrong and I became deathly ill … I was a very, very sick man,” Scott recalls.

He doesn’t remember a tick or the tell-tale bullseye rash circling a tick bite but figures one of the arachnids latched on for a ride during his past work as an agrologist.

He’ll never know exactly how he contracted Lyme disease, but with a master’s in science behind him, Scott has since dedicated his time as a self-proclaimed research scientist to a mission of getting to the bottom of “what’s going on here in Canada” with tick-borne ills.

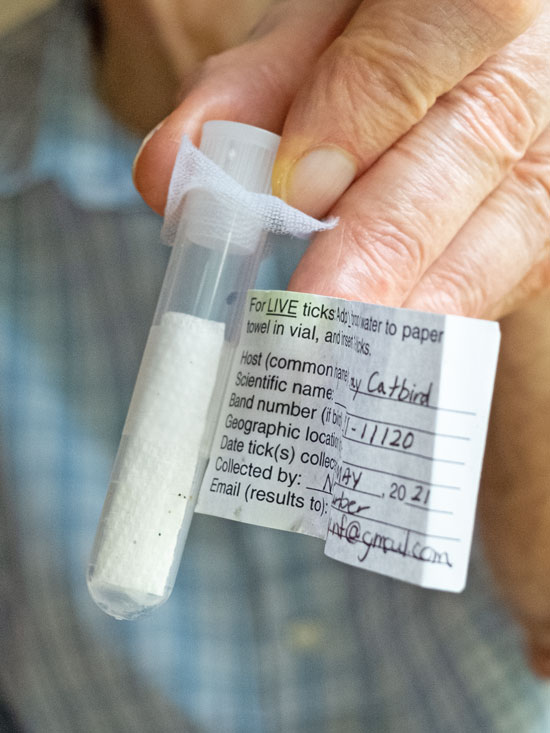

Ticked – Fergus resident John Scott holds a container with a black-legged tick collected off a songbird.

Captive ticks—usually of the black-legged variety, known also as deer ticks—are sent to him via mail from across the country.

The ticks are either kept by Scott for his own research or sent away to be tested for one of at least nine zoonotic diseases, including Lyme, potentially festering within their sinister bodies.

Scott’s tick research has been published in various journals and he has also been the recipient of a Governor General Sovereign’s Medal in 2016 for his voluntary work.

Now, the 75-year-old Fergus resident says he’s made a new discovery.

Published in the Switzerland-based online open-access journal Diagnostics in May, Scott’s findings contend to show a particular species of Babesia (buh•bee•zhuh)—previously thought to only cause disease in elk, deer and other livestock—could also be pathogenic to humans via a bite from a black-legged tick.

Babesia, a parasite transmitted by ticks and infecting red blood cells, has over 100 different species which cause the malaria-like disease babesiosis (buh•bee•zee•oh•sis). Night sweats, chills, fever, fatigue, muscle aches and poor sleep are all accompanying symptoms.

Though babesiosis in humans is nothing new (the first discovery was in a farmer in 1957) it’s the presence of the particular species Babesia odocoilei (oh•doh•koh•lee•eye) which Scott says is a novel discovery.

“It’s a first—we’re the first ones to show it’s pathogenic in humans,” he recently said from his Fergus home.

Field work

Tagged – A black-legged tick collected from a “catbird” is tagged and held in a container by John Scott.

A year-and-a-half ago, 19 participants ranging from 16 to 76 years-old and sourced from Lyme disease support groups in Ontario, rolled their sleeves to part ways with some blood.

In the study, authored in tandem with research colleagues at the University of California Davis and the University of Agriculture Faisalabad in Pakistan, B. odocoilei was said to be detected in two subjects.

A 23-year-old woman and a 74-year-old man claiming they had been bitten by ticks, had DNA from their blood sequenced against sequences of B. odocoilei from GenBank returning 99.55 per cent and 99.77% closeness to the GenBank sequences, respectively.

That may seem about spot-on, but when it comes to genetics, minor decimal points have massive consequences.

Still, the study reads samples had “very close proximity” to the type strains in GenBank, an open-access databank of publicly available DNA sequences operated by the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Criticism and accolades

The Advertiser reached out to Dr. Kieran Moore (before he became Ontario’s chief medical officer of health) in his position as director of the Canadian Lyme Disease Research Network for his views on Scott’s study.

Moore suggested the study’s analysis was “very limited” and declined to speak with the Advertiser which then reached out to Public Health Ontario deputy chief of microbiology and laboratory science Dr. Samir Patel at Moore’s suggestion.

Patel too declined to provide comment and suggested the paper contact Dr. Robbin Lindsay at Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory “as he has been testing ticks for pathogens” across the county.

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) media spokesperson Anna Maddison said in an email to the Advertiser that Lindsay had no availability to speak with a reporter.

Maddison did, however, provide a nearly 500-word response across three paragraphs outlining “the Public Health Agency of Canada’s position on the study” which led off by saying the study “provides some interesting observations” but falls short of firmly establishing “a causal link between presence of the organism’s DNA and the symptoms self-reported by the participants.”

The PHAC response also called into question whether the positive subjects actually had B. odocoilei present in their bodies or whether they had only been exposed and stated the participants could have become sick from other causes.

“Taken together, this study provides some novel observations on possible human infection with B. odocoilei; however, much more research would be required to confirm that this organism is a human pathogen,” the PHAC response read.

Dr. Raphael Stricker, an academic editor on the study and a San Francisco-based Lyme disease medical doctor of 27 years, called Scott’s work “ground-breaking” when reached by the Advertiser for comment.

“The big advance of John’s finding is that if we have another pathogen that we know about, we can test for it and we can see if that’s what’s causing the symptoms,” Stricker said, adding larger population studies are needed to see where and how common the disease is.

Another doctor specializing in Lyme disease, New York-based Dr. Kenneth Liegner, called Scott’s work “pioneering.” Liegner was not involved with the study.

“First of all, if this is valid, he has uncovered a new little ecosystem of babesiosis,” Liegner said.

Tick-borne diseases, Liegner said, are especially problematic because diagnostics and treatments leave much to be desired.

“The ramifications are, you have a treatable disease that’s not being diagnosed or treated, and therefore, people are suffering,” Leigner said of not testing for the odocoilei species.

Scott fears those undiagnosed with babesiosis could be misdiagnosed with similarly-presenting malaria or the other two species of Babesia pathogenic to humans—duncani and microti—which odocoilei mimics in fluid blood testing.

“Right now, the labs have to get up to speed so they test this properly,” Scott remarked, saying genetic testing is what’s needed.

Finding Babesia

Justin Wood—founder of Ontario-based Geneticks, the first private tick testing lab in Canada—is doing exactly that and hopes to offer testing for the odocoilei species within the summertime.

“John came out with this paper and he sent it to me, and I said, ‘okay, great,’ and we jumped right on the train of validating that testing that we had sort of been working on in the background,” Wood said.

Wood, who has also received a Lyme disease diagnosis, uses “nested PCR” testing to differentiate genetics down to the species level, testing around 1,500 ticks annually with the Ottawa area, through Kingston and along the north shore of Lake Ontario, seeing the highest positivity rates for Lyme disease.

“The important thing here is that [the public] know that this infectious disease is tied in with ticks … if they get bitten by a tick, they know that they’ve been bitten by a tick, they should be tested for not only Lyme disease, but they should be tested for human babesiosis,” Scott said, going on to claim he’s found ticks with B. odocoilei in Centre Wellington.

Secured – John Scott reseals a container holding a black-legged tick after showing off the tiny arachnid inside his Fergus residence.

In PHAC’s statement to the Advertiser it was said testing at the National Reference Centre for Parasitology at McGill University is “sufficiently cross-reactive to detect a suite of Babesia species, including B. odocoilei” and the agency’s National Microbiology Laboratory also has the “capacity to detect, using molecular based testing like PCR, a range of Babesia species that may infect people, including B. odocoilei.”

The agency is working to make babesiosis a nationally notifiable disease and said there are ongoing efforts to educate physicians about tickborne diseases in addition to Lyme “to ensure patients are promptly identified and treated.”