AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND – “If you had told me when I was dropping out of high school that 50 years later a kid from Clifford would be running a space program and lecturing to a class of 1,000 students at the biggest university in a country on the other side of the world, let’s just say I would have been sceptical.”

Unlikely as it sounds, that’s exactly the position Jim Hefkey has found himself in, following a winding life path from a small Wellington County village to Auckland, New Zealand, where his class at the University of Auckland is about to launch that country’s first space satellite.

Hefkey’s interest in space began when he was eight years old and the space race between the U.S. and Soviet Union was making big news.

“When John Glenn orbited the Earth in February 1962, I decided to add my congratulations,” Hefkey recalls.

“I wrote a short note, addressed the envelope to ‘John Glenn, Houston, Texas, USA,’ put a two-cent stamp on it and dropped it in the Clifford post office box.”

Weeks later he was playing across town when his mother sent word he was required at home immediately.

“It seems I had received a letter from NASA. I had not told anyone about my note, so it was a bit of a surprise for my parents,” he said.

“My older brother John could not wait for me to be found and went ahead and opened it first.”

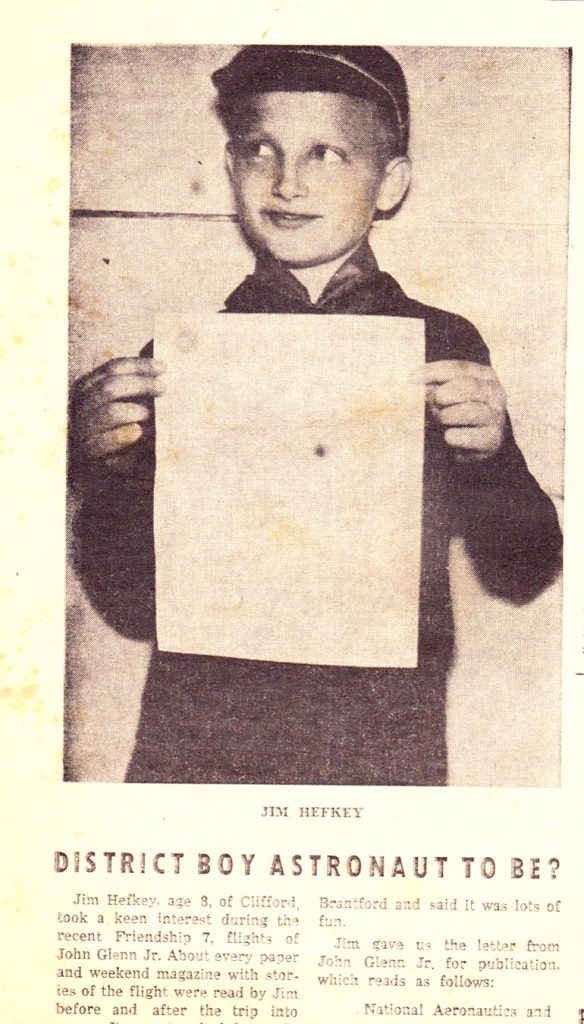

The ‘write’ stuff – An eight-year-old Jim Hefkey received a letter from astronaut John Glenn in response to a letter he sent to the U.S. space pioneer in 1962. The correspondence earned the young Clifford resident a story with a photograph in the Harriston Review newspaper. Submitted photo

The letter earned the young space enthusiast a story, complete with his photo holding the letter, in the local newspaper, the Harriston Review, and led to a summer spent largely on the back deck of his family’s home using an old wringer washing machine as a space capsule and “flying make believe adventures into space.”

Hefkey’s space dreams got a boost years later while attending Norwell District Secondary School, where his interests included Army Cadets, dark room photography and rockets.

“With the cadets, I spent a summer climbing in the Rocky Mountains near Banff. A couple of us students also set up the first dark room at Norwell, having been encouraged by Art Carr from the Palmerston Observer,” he notes.

About the time of the moon landings (1969) a classmate of Hefkey’s found out about a new hobby: flying model rockets.

“I was in. Model rocket motors were a restricted item at the time so one of our teachers drove all the way to Toronto to buy them for us,” he said.

“We built our kit-set rockets and flew them several times on a farm somewhere outside of Palmerston.

“I managed to keep all my fingers in spite of at least one memorable explosion in the front yard. Mother was not amused. When I cleaned out the attic of my parents’ house in 2012 or ‘13 I found a box of rocket plans from my high school years that mom had kept.”

By the time he was 16, Hefkey was finding school “pretty boring” and, with failing grades, he dropped out.

“I got a job literally digging ditches (farm drainage), which helped me clear my head and convinced me to go back to school,” he said.

During a visit to the school office, Hefkey happened upon a brochure from Conestoga College marketing a new course called Fluid Power Technician.

“I had never heard of industrial pneumatics and hydraulics before. On a whim I filled out the application form and – surprise – got accepted. I am convinced they were desperate for students to fill this new program,” Hefkey speculated.

After graduating from Conestoga in 1975, Hefkey moved to Toronto and for the next 10 years held a variety of industrial jobs working with the design and application of control systems, assembly tooling, and creating automatic assembly machinery.

“Around 1979-80 I was wandering down Queen Street one weekend and spotted some model rocket kits in a shop window. An old interest was rekindled and I walked out of the hobby shop with a new rocket kit and some motors,” he recalled.

“The company I was working for was on the northern service road of the QEW at Oakville and backed on to some as yet undeveloped land so I used that as my launch site. Imagine my surprise when two police cars came bouncing across the fields at speed and skidded to a halt beside me. It seems a security guard in a nearby building had thought I might be a terrorist and called the cops.

“I explained what I was doing, showed them the rocket and let them witness a launch. They left satisfied and enlightened. I stopped flying rockets after a couple of months for new hobbies.”

In Toronto, Hefkey met his future wife, Lynn, who was planning to emigrate back home to New Zealand.

Looking for a change in career path, he joined her and moved to Auckland in December of 1985 at the age of 32.

Starting out in industrial pneumatics and control systems, Hefkey regularly undertook new training – some industry based and some through the university.

“Having already completed a few university-based engineering courses, in my early 40s I undertook a two-year business diploma in engineering management,” he explained.

“Several years later, with more training under my belt, I took on another major program and in 2001 graduated with a Masters of Engineering in manufacturing systems from the University of Auckland. These qualifications along with the contacts I made eventually led to part-time teaching in engineering management at the university.

“This began when I started my own business and has continued since.”

Hefkey said he got back into amateur rocketry some time before 2010, noting hobby rocketry had changed markedly over the years.

“A new branch of the sport was ‘high power rocketry,’ with larger rockets and flights to several kilometres altitude. I was hooked,” he said.

“After building and flying a couple of small- and medium-size kits, I was soon designing and flying my own single stage and multi-stage rockets to several kilometres altitude.

“Some of these rockets were over three metres in length and had four engines. Stage ignition and parachute deployment were controlled by on-board flight computers and had GPS tracking. We travelled overseas a couple of times to launch large amateur rockets in the Australian outback.”

At the time, he notes there were no space programs being taught in New Zealand at the tertiary level. Working part-time at the University of Auckland, he began helping an organization that was running small rocketry programs for intermediate and high school students.

Rocket class – Clifford native Jim Hefkey with students at the New Zealand Rocketry Association National Launch day in February. Students in Hefkey’s space systems program are challenged to build a computerized payload to achieve a specific task, launch the payloads to about one kilometre altitude then eject them out of the rocket. As they return by parachute the computer and cameras transmit the required data to a ground station. Submitted photo

“Thinking bigger, I started to lobby for these activities to be embedded in the school curriculum,” said Hefky, who in 2015 became aware of a “CanSat Leaders Training Program” (CLTP) being offered by the University Space Engineering Consortium (UNISEC) in Japan.

He paid his own way and tuition fees to attend the course in Sapporo, Japan.

His new contacts in Japan arranged for the University of Tokyo and Canon Space Systems to send two people, with a display satellite, to attend a conference with Hefkey on the future of farming.

“I took the opportunity and organized a public forum for our two guests to speak. In addition, the regional government used their extensive contacts list and organized an ‘invitation only’ event for us at their offices,” he explained.

“Here we met with key people from business and industry, local and national government, tertiary education, as well as the New Zealand military. From these events I found it much easier to contact people and discuss the future of space activities. I started receiving invitations to attend events as a speaker on space activities.”

Several months later Hefkey received a phone call from the Dean of the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Auckland.

“We want to build a satellite and launch it into space. Would you like to come and run the program?” he was asked.

“After getting over the shock I explained that I was an eager enthusiast but not a technical expert on the topic,” said Hefkey.

“His reply was that I was more qualified than anyone else they had at the moment, and I was already on the (part-time) payroll. After some negotiation we agreed on a full-time, three-year contract teaching engineering management and running the space program.”

Hefkey put his own business ventures on hold at that point.

The “Auckland Programme for Space Systems” (APSS) is open to any second- or third-year undergraduate student from any faculty enrolled at the University of Auckland. Students are required to form their own mixed disciplinary teams to identify a problem or need for society and then create a proposal solving that problem.

The three winners of this competition are selected as: Most Benefit to New Zealand, Most Ambitious, and Most Likely to Succeed. Technical content is important but is only one factor in the judging.

A member of the Auckland Programme for Space Systems staff checks out a student satellite project set for launch later this year. Submitted photo

This forces students from engineering and science to work with the business, arts, and other faculty students to create a comprehensive plan that goes beyond the technical, Hefkly explained.

The winners of the Most Likely to Succeed category will go on to build an actual satellite over the next two years and have it launched into space.

“Setting the program up this way is unique. A couple of years ago the head of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) visited my office and once the program was explained she suggested I present at the UNOOSA conference in South Africa. I have spoken at other events about the program, most recently in Tokyo and, COVID-19 willing, at an upcoming small satellite conference in Utah,” said Hefkey.

“There have been lots of other exciting things happen over the past few years, from national and international business and education collaborations, to advising on the establishment of the New Zealand Space Agency.”

A new competition begins each year and the program is now into its fourth cycle. The first satellite, APSS1, is scheduled to be launched this year.

“It was going to be July, but COVID-19 has set the schedule back,” Hefkey notes.

The launch will be the first for a New Zealand-manufactured satellite with an operational payload. It will be launched from New Zealand soil by a pioneering domestic company, Rocket Lab.

The low Earth orbit (LEO) will be at an altitude of between 400 and 500 kilometres and will circle the Earth once every 90 minutes or so. It is expected to stay operational for between 12 and 24 months. At the end of life it will burn up on re-entry to the atmosphere.

The student team has built a satellite that will measure electron activity in the upper atmosphere.

“There is an unproven theory that electron activity increases just before an earthquake and the team wants to try and measure this and correlate any spike in activity to an actual earthquake. New Zealand is highly prone to earthquakes and this theory may be useful as one tool in an effort to predict earthquakes,” explains Hefkey.

There are two more satellites in the research and construction phase. APSS2 is well underway and will deploy an electrodynamic tether to test its ability to de-orbit a satellite. This is aimed at finding ways to reduce the increasing amount of space junk in low Earth orbit.

JIM HEFKEY

The mission ideas are entirely of the students’ choosing, said Hefkey,

“Whether the satellite succeeds or not is almost secondary to the main goal of the program,” he adds.

“We don’t know what the future holds for our graduates. We do know that they will be asked to solve increasingly complex problems, in an unfamiliar environment, working with teams of people that do not all think alike.

“Space is the perfect analogue to help prepare our students for the future they face,” Hefkey observes.

With the success of the APSS program, the University of Auckland has now attracted funding to create the Auckland Space Institute.

Staffed by internationally recognized space researchers, it has attracted research projects, funds and students from around the world, Hefkey notes.