The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

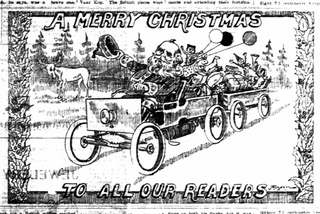

A while ago I stumbled upon an interesting image of Santa Claus.

Rather than riding his sleigh drawn by reindeer, he was driving a newfangled automobile, towing a wagon overloaded with gifts. One hand gripped the tiller (most early cars did not have steering wheels) while the other raised his hat in a salute. A forlorn, unemployed reindeer watched from the side.

The drawing appeared on a page of what was once known as boiler plate. These were newspaper pages made up usually at Toronto, with general interest material and advertisements.

They were distributed either as printing plates or preprinted pages to weekly papers. Not every weekly used such material, but many did: an eight-page paper would typically have four pages of boiler plate and four of local news and advertisements.

The image, therefore, enjoyed wide circulation: probably half of the 14 weeklies published in Wellington in 1899 carried it. What is surprising is the date: 1899.

It is safe to say that at least half the people who originally saw that drawing had never seen an automobile in real life, and would not see one for another three or four years. To us the image is quaint, but 125 years ago it was thoroughly modern, even futuristic.

Much of what we consider to be a staple of the Christmas season has its roots in the last couple of decades of the 19th century.

In 1870, newspapers barely mentioned Christmas, in either news stories or advertisements. Most stores closed, but some did not. Scots especially played down Christmas, preferring to hold their celebrations on Hogmanay, Jan. 1. Many Protestant extremists felt the same way, viewing Dec. 25 as a Romish intrusion.

That changed slowly during the 1870s, and rapidly in the 1890s. The Christmas of 1899, of which the Santa-in-the-auto sketch was a part, seems familiar to us: a largely secular holiday with a strong religious element, an opportunity to reunite with friends and family, and an occasion for spending on consumer items.

A lengthy Christmas sales season is nothing new. Merchants trotted out their season advertisements in the first week of December in 1899. Some, such as Henry Irvine of Drayton, began in November. But not all merchants took out Christmas advertisements.

In the Drayton Advocate, only five of the 17 retail advertisers mentioned Christmas. In other papers the percentage was higher, but seldom more than half.

The non-advertisers included important stores, such as Frank Clark, the largest dry goods dealer in Elora. Others skirted an explicit mention of Christmas, such as William Campbell in Elora, who ran a “Great Discount Clearing Sale” from Dec. 14 to 23, featuring reductions of 10 to 50% on items suitable as gifts.

A few advertisers used a Christmas tie-in for regular merchandise. Elora druggist R.D. Norris noted that “Santa Claus recommends us to the public,” and suggested that people purchase a bottle or two of Winter’s Cough Cure so that their holidays would not be marred by illness. That compound would certainly relieve seasonal stress. It was liberally laced with codeine.

Most churches held Christmas services, Christmas tree celebrations for youngsters and seasonal concerts, but there were a few holdouts. Stirton Methodist was one of the churches clinging to older ideas in 1899. It did not have Christmas functions, but scheduled a “New Year’s Entertainment and New Year’s Tree,” a concert combined with gift giving for children.

Alma Presbyterian also favoured New Year’s, with its anniversary service on Dec. 31 and a dinner on Jan. 1, featuring a full-course meal and entertainment for 25 cents.

Fowl for Christmas dinner, though not universally favoured, was becoming a tradition with many families. The poultry business in 1899 was very much a decentralized one.

Small-town merchants often accepted poultry as trade, and a few operated a sideline in Christmas birds. In 1899 John Lunz of Drayton wanted 1,500 live turkeys, “off feed for 24 hours.”

Henry Irvine wanted 4,000 pounds of dressed turkeys, geese, ducks and chickens for resale to his customers. The growing fashion for holiday poultry offered a profitable sideline for farmers.

Overall, people were in a good mood for the Christmas of 1899. The economy had been on the upswing for several years, and agricultural prices were improving after a generation in the doldrums. The big news story in 1899 was the South African War. By Christmas of 1899 the tide had turned against the Boers, who in the early stages of the conflict had humiliated the British and Canadian forces.

Christmas charity was also a part of that long-ago season. The big campaign that year was for the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. That institution was $30,000 in debt, and ran a province-wide campaign to wipe the deficit off its books.

*This column was originally published in the Wellington Advertiser on Dec. 22, 2006.