ABOYNE – When nurse Alice Hindley boarded the S.S. Adriatic in Halifax on May 19, 1916, she couldn’t have known what lay in store on the other side of the Atlantic.

It’s true that nearly two years into the First World War, the allure of battle had since been drenched in the blood of millions of lives that had been wiped from the Earth.

But Alice still couldn’t have prepared for what she would see in England, and later in France, not far from the Western Front.

The nursing profession was in its infancy. Nurses accounted for about two per cent of the female workforce in Canada in 1911, according to Canada’s fifth census.

The war provided thousands of nurses short on job prospects a way to make money and answer a gripping sense of duty.

NURSING SISTER ALICE EVA HINDLEY (Ph. 15427, Wellington County Museum and Archives)

So, at 32 years old, unmarried, and educated at the Hamilton General Hospital Training School, Alice Eva Hindley left her job at Scott Hospital in Saskatchewan and enlisted as a nursing sister in the First World War, following in the spirit of Florence Nightingale, who died just four years before Britain declared war on the German Empire, and is widely credited for laying the foundations of modern nursing.

Nursing in war was an even newer concept at the time.

Nightingale trained nurses and cared for soldiers in Constantinople, during the Crimean War, proving nurses’ usefulness to the wounded.

When war broke out in 1914, Canada, woefully ill-prepared militarily and on the medical front, was dragged into the fray only having used nurses for the first time in battle during the Boer War in 1899.

The same year, the Militia Medical Service was formed and later absorbed into the Canadian Army Medical Corps in 1904, with only five permanent nurses.

The first contingent of 100 nurses was dispatched from across Canada to England in 1914. By the end of the war, at least 2,411 Canadian women had served overseas as nursing sisters.

***

Over a century later, on Oct. 26, Alice’s relatives, some who have never met before, are gathered in a textile storage room at the Wellington County Museum and Archives (WCMA).

Alice’s nursing uniform, a light-blue cotton dress with a white apron and two First Lieutenant’s stars affixed at the shoulders, is cleaned and mounted for display. The complete uniform, with a white veil worn while on duty, led to the nurses being known as “bluebirds” by soldiers.

Nursing Sister Alice Hindley’s uniform, seen at the Wellington County Museum and Archives on Oct. 26. Photo by Jordan Snobelen

Alice’s uniform has two small rips on the right sleeve, and accompanying straps and cuffs are yellowed with age.

Next to the dress, is a navy-blue coat with golden buttons.

Rudimentary tools of the trade, including scalpels, scissors, forceps, and an old thermometer, have been laid out and organized neatly in a box.

In other boxes are medals, clasps and buttons, all displayed for the roughly 14 family members who discuss the memorabilia and their memories of “Aunt Allie,” as she was affectionately known.

Scalpels, forceps, scissors, dental tools and a thermometer once belonging to Nursing Sister Alice Hindley are presented at the Wellington County Museum and Archives on Oct. 26. Photo by Jordan Snobelen

Before arriving here, the instruments had been confined to a desk drawer, out of sight and out of mind, says Cathy Parr Hughes, who received the items from her mother.

As for Alice’s uniform, also in Hughes’ care, it was used as a Halloween costume on more than one occasion, she admitted.

“It’s a miracle it survived,” she remarked.

Norma Hindley can be credited for the gathering and reuniting of Alice’s wartime wares.

Recently retired, she found herself cleaning up around the house when she stumbled upon some old photographs without names or dates on the back.

She started an email chain to find information about the Hindleys.

“Everybody kind of chimed in,” Norma said, which led to responses from Cathy, who had the uniform and instruments, and Peter Hindley, who had a collection of Alice’s medals in a drawer.

A British War Medal and Victory Medal awarded to Nursing Sister Alice Hindley. Photo by Jordan Snobelen

“We made some discoveries, there’s lots of stories that get passed around, and I think that’s part of the fun, and if we don’t retain them now the next generation isn’t even going to know,” Cathy said.

She reached out to the museum, enquiring if the county would be interested in having the items.

“Obviously I was interested,” museum curator Hailey Johnston said. “It very much out-of-the-blue came to us, and I was just thrilled that it did.”

Conservator Emily Benedict cleaned, mounted, and assembled the items, and curatorial assistant Amy Dunlop gathered additional research on the items, catalogued them, and created records which can be viewed online.

The museum’s role, Dunlop said, is to highlight stories of people and places in the community through collections such as this.

In fact, little is known about Alice’s story overseas. Lore has been handed down, but there are no letters saved and knowledge comes second-hand.

The only true, documentary evidence comes from military service records held by Library and Archives Canada.

***

The S.S. Adriatic docked in England on May 30, 1916.

Alice was assigned to the No. 8 Stationary Hospital—a misnomer for the unit as they were neither stationary, nor a hospital—and frequently relocated around France, setting up and tearing down canvas, tented wards and beds for their patients as they went.

Alice began working at the Moore Barracks, one of five hospital units located at the Shorncliffe Army Camp in Kent, England.

In 1917, the No. 8 Stationary Hospital nursing sisters—their nursing ranks fluctuating between 28 and 43 throughout the war—crossed the English Channel into France.

Stretcher bearers and German prisoners bringing in wounded Vimy Ridge soldiers. (National Archives of Canada)

When a soldier was injured on the front lines, a “field ambulance” unit would evacuate them to a casualty clearing station.

From there, they might end up at a general hospital, or a stationary hospital, where nurses would clean and bandage wounds, provide tetanus shots and clean clothing, and monitor the men’s condition.

Infection was rampant in the unsanitary muck and mire of the trenches, an influenza pandemic swept through Europe in 1918, and new weaponry and heinous forms of warfare led to catastrophic injuries from shrapnel wounds and mustard gas attacks—all of which nurses didn’t have the skills and experience to deal with.

Antibiotics weren’t around and advancements in medical techniques weren’t yet born by the Second World War.

Nurses also had to respond to horrifying psychological trauma, presenting in soldiers through night terrors, bedwetting and suicide.

Despite nurses’ limitations, patients streamed in from the fields by the thousands, often overwhelming nursing staff and quickly pushing the make-do hospitals to capacity.

Stationary hospitals started out with 200 beds before increasing capacity to between 400 and 650 beds by 1915, and at one location, over 1,000.

General view of No. 8. Stationary Hospital, Wimereux, October 1916. (Photograph Q 29146 – IWM)

By 1918, Canada operated 16 general hospitals, 10 stationary hospitals, and four casualty clearing stations.

In November that year, nurses from the No. 8 Stationary Hospital were sent to other Canadian hospitals.

Alice was attached to No. 1, 13 and 15 Canadian General Hospitals which specialized in treating jaw, ear, nose and throat, and fracture injuries.

On Nov. 11, 1918 an armistice was signed bringing an end to the war, but nurses continued providing care, including to repatriated British soldiers and German prisoners of war.

Nearly three years after enlisting, Alice and the remainder of the No. 8 Stationary Hospital returned to Canada on the S.S. Scotian on Feb. 19, 1919.

Nursing Sister Alice Hindley, facing the camera, is seen with soldiers. Image Courtesy of Wellington County Museum and Archives

From 1916 to 1919, Alice’s unit had travelled from England to Boulogne-sur-Mer, Camiers, Charmes, Rouen, and finally, Dunkirk.

It’s unknown how many men Alice would have cared for during her time overseas, but government records show the unit treated 3,226 patients in England, and another 7,924 in France, totalling 11,152 patients.

Alice was one of 446 Canadian nursing members awarded the Associate Royal Red Cross for special devotion and competency in nursing duties, or for the performance of an act of bravery and devotion.

The Associate Royal Red Cross awarded to Nursing Sister Alice Hindley in 1919. Photo by Jordan Snobelen

***

When she returned to Canada, Alice remained in military ranks, working at St. Andrews Military and Toronto Dominion Orthopedic hospitals in 1920 before leaving in August that year and earning a diploma in public health and social welfare.

She drove across modern-day Halton and Peel Region and Wellington, Perth, Huron, and Grey counties while working as an investigator for mothers receiving government social assistance.

The work, a family history booklet states, “suited her adventurous, out-of-doors nature.”

Travelling became an active part of her life and she embarked across Scotland, England, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Holland, Belgium and Austria in 1930.

In 1936, she was part of the Pilgrimage to Vimy for the dedication of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France. Her cousin, George Cecil Thomas, who also served in the war, joined her.

Later, she visited the west and east coasts of the Uniteds States and, in 1951, Mexico.

Peter says Alice loved to drive, and loved nature.

He remembers travelling with her to the Cartwright Waterfall where she would point out all the different birds. She could hold her own fishing and horseback riding too.

In her 70s, Alice bought a 1957 Chevy in canary yellow, and even at that age wasn’t afraid to push the pedal.

Peter described her as a leader, someone who was friendly and approachable and loved by her family.

“Everyone thought the world of aunt Alice,” he said. “She was the one who made life fun.”

Each Christmas, she brought party poppers and hats to wear, Peter said of his fondest memory of “Aunt Allie.”

Alice died in 1968, at age 84, and is buried in the Johnson-Eramosa Union Cemetery in Guelph/Eramosa.

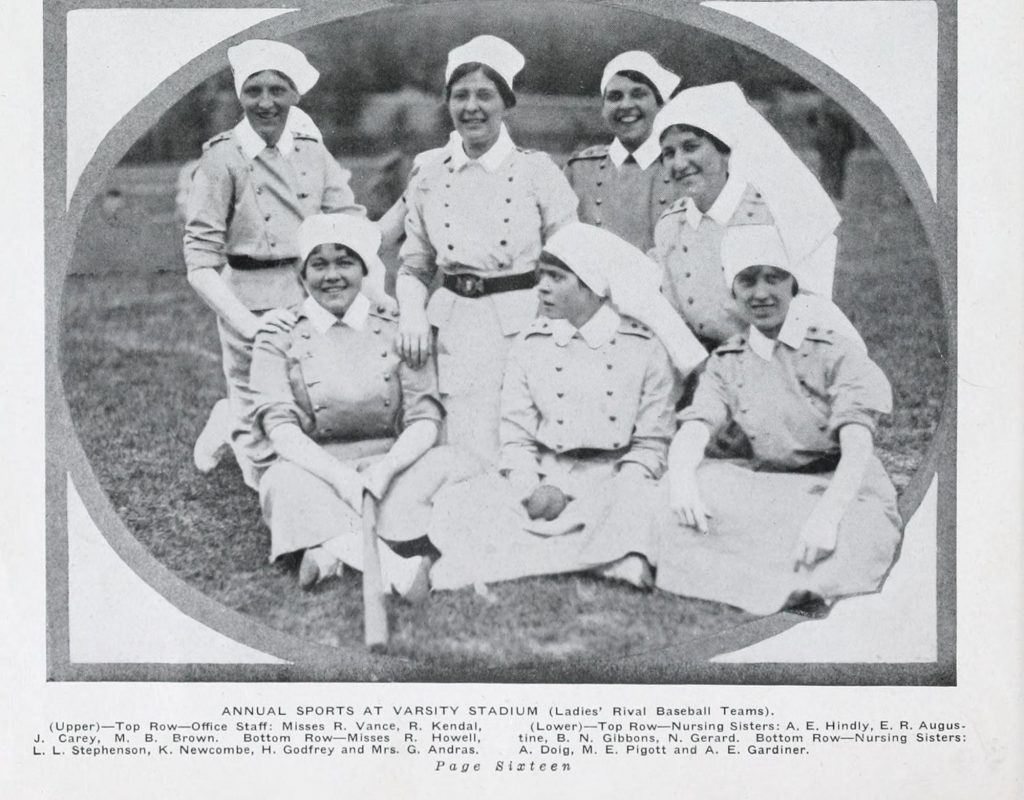

Nursing Sister Alice Hindley, top right, is seen with other nursing sisters at the Dominion Orthopaedic Hospital in Toronto.

She rarely, if ever, spoke about her experiences during the Great War.

“She kept that pretty quiet,” Peter said.

Instead, she left behind memories of happy times and her worldly travels.

Alice spent the remainder of her life driving the roads of Wellington County, enjoying nature, and looking after her nieces and nephews who were never far.

“Not only did she serve her country, but she was well-loved by her family,” Peter said.

Cathy hopes by donating Alice’s belongings to the museum, they will be preserved and highlight the role women played in the war.

“That part of history didn’t get written and it needs to be,” she said. “It needs to be shared.”

Alice Hindley’s uniform, medals and medical instruments are on display on the first level of the Wellington County Museum and Archives until Nov. 14.