WELLINGTON COUNTY – Poultry producers are contending with a different sort of viral outbreak following several positive cases of avian influenza discovered in Wellington County poultry flocks.

A highly pathogenic H5N1 subtype has, as of April 4, been confirmed by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) in six southwestern Ontario flocks, of which two are in the county.

Also known as “bird flu,” the virus has been around for over a century, infecting the respiratory tracts of many types of birds, both domesticated and wild.

Subtypes are separated into two categories: low and high pathogenicity, depending on how sick birds get.

Although the virus does not present a food safety risk, the CFIA pays particular attention to “H5” subtypes because they mutate from low to high pathogenicity after infecting domestic birds, and cause high mortality.

It’s also the subtype most responsible for causing severe illness and death in people, with over half of human infections resulting in death, according to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention.

The virus transmits to humans via the eyes, nose, mouth and can be inhaled through aerosols, although it’s uncommon.

According to the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, “there have been very rare cases when the avian virus has spread from one ill person to another, but the transmission has not been observed to go beyond one person.”

Most at risk of infection are farmers, their family members and workers who have worked around birds and come in contact with: infected birds; manure and litter; contaminated surfaces, vehicles, equipment, clothing, and footwear; and infected birds when defeathering.

The virus is shed by birds in their feces, contaminating the birds’ environment and spreading rapidly in confinement and surviving for many days in litter, feed, water, soil, dead birds, eggs and feathers. The incubation period ranges between two and 14 days.

Broiler chickens. (Photo by Laura Gil Martinez, Creative Commons license)

Outbreaks of H5N1 have been confirmed in a flock of turkeys in Guelph/Eramosa (March 27), and in ducks in Centre Wellington (April 4).

The CFIA initially received reports of high mortality in flocks via veterinarians, CFIA officials told the Advertiser in an email.

“As per the standard procedure, samples were sent to the Animal Health Lab in Guelph for preliminary testing. Subsequently, the National Centre for Foreign Animal Disease in Winnipeg confirmed these samples as highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1,” states the email.

Until last month, Ontario had remained free of avian influenza since 2015, when a major outbreak lasting seven months spread from a turkey farm near Woodstock to additional commercial turkey and chicken operations.

As a result of the 2015 outbreak, over 50 million birds died globally and trade was significantly impacted. Trade is once again being impacted by import and export restrictions imposed on poultry.

In response to the recent outbreaks, the CFIA has assigned a group of veterinarians, executive management and field staff to coordinate across government tiers and manage the outbreaks.

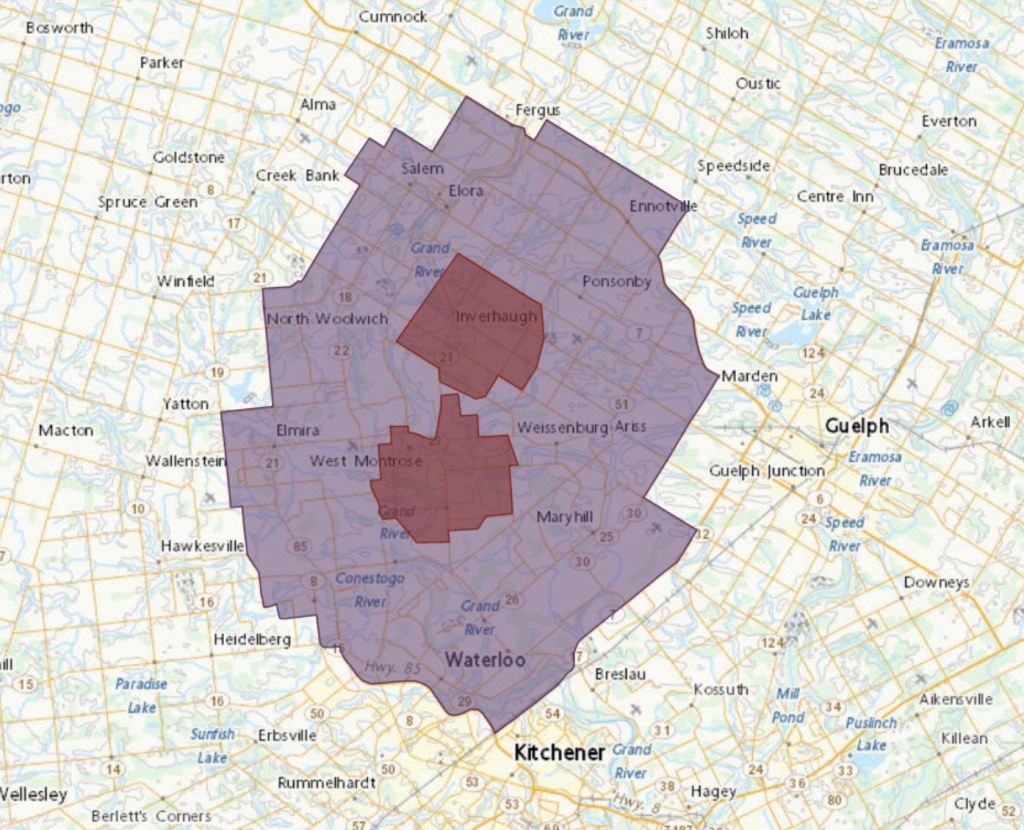

To prevent the virus’ spread, the feds established “primary control zones” around diseased locations, restricting the movement of birds. Any birds that have not already succumbed to the virus are euthanized and disposed of.

To prevent the spread of avian influenza in Ontario, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has established primary control zones in areas where disease has been identified. Seen in red are infection zones and in purple is the primary control zone. (CFIA map)

Outbreaks in Canada were first discovered in December at five premises (two commercial and three backyard) in Newfoundland and Labrador and another the following month in Nova Scotia.

Some 13,252 birds died with mortality reported to be as high as 85%.

In a February reportable disease summary published by the Feather Board Command Centre (FBCC), an industry group consisting of Ontario’s featherboards and stakeholders, it was reported the virus was “spreading in areas where poultry may directly or indirectly contact droppings from migrating waterfowl.”

Nearly 70 million birds have either died or been culled in more than 51 countries because of outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza since September.

“The coming weeks will test the biosecurity upgrades that farms, businesses and government agencies have made since 2015,” the FBCC summary added.

The first sign of the virus’ arrival in Ontario appears to come from a March 21 Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) notice stating a red-tailed hawk with neurological deficits, found in the Region of Waterloo, had tested positive for H5N1.

CFIA officials say the “source of the outbreak is most likely the wild bird population.”

“Scientific evidence indicates that the avian influenza virus circulates naturally in wild birds, and is spread through migratory birds.”

Migratory Gadwalls are seen at the Arapaho National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo by Tom Koerner, Creative Commons licence)

Avian influenza has been confirmed this year in all four North American flyways used by wild, migrating birds.

According to OMAFRA, the virus can be transmitted to poultry barns by “breaches in biosecurity and is most often transmitted from one infected flock to another by movement of infected birds or contaminated equipment or people.”

On March 26, the FBCC issued a heightened biosecurity advisory to all poultry stakeholders throughout the province.

“Implementing and adhering to biosecurity best management practices is critical to preventing the introduction and spread of the disease,” states a March 27 OMAFRA avian influenza disease update.

“Producer and owner diligence is pivotal to select, implement and maintain specific, effective biosecurity measures.”

OMAFRA encourages poultry farmers impacted by avian influenza to participate in risk management programs and to contact Agricorp (1-888-247-4999) for more information.

For more information on how to protect your commercial or backyard flock, visit inspection.canada.ca.

Individuals are encouraged to report findings of dead waterfowl and shorebirds to the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative by visiting cwhc.wildlifesubmissions.org.