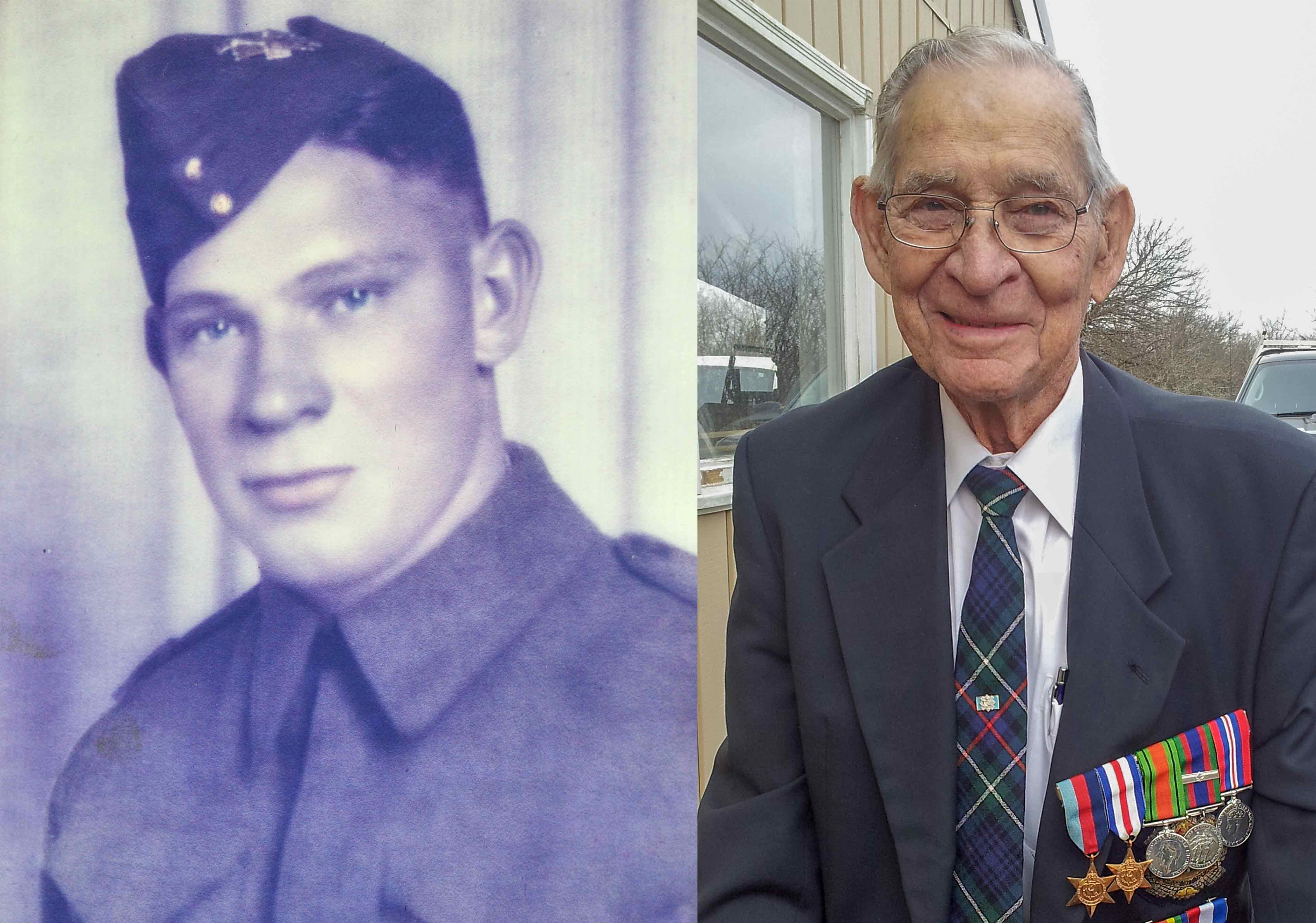

This article was originally published in 2014, for the 70th anniversary of D-Day. Ken Waters died about seven months after it was written.

WELLINGTON NORTH – In the summer of 1941, Ken Waters left military training in Nova Scotia and was shipped to England.

A communications officer with the Highland Light Infantry of the Canadian army, Waters trained there for almost three years, including months of rigorous landing exercises.

His unit was often taken out on a barge and the men, weighed down by their full gear, were told to jump off.

“You (sank) about 18 feet, then you had to come up and swim to shore, which was a good 150 yards,” said Waters, who had “no idea” the drills were training for the Normandy invasion on June 6, 1944.

But nothing could have prepared him for what he saw when he landed on Juno Beach on D-Day, over an hour after the beaches were to be secured.

“They weren’t too secure,” he said with a wry smile.

“It was chaos. There were so many shells coming in, we had to keep digging holes.”

Compounding the situation, Waters said, was the very narrow area of beach on which his unit had to advance. He estimates his group advanced about 100 metres at a time, digging holes along the way to shield themselves from the German barrage.

“We knew we had to go inland because we didn’t want to go the other way,” Waters recalled recently from the kitchen table of his home north of Arthur.

Now 93, Waters is still troubled by the human casualties he witnessed that day.

“It was the worst thing I ever saw,” he said quietly, describing one particularly disturbing scene of shot-up Canadian soldiers hanging out of a tank that was disabled during the invasion.

Waters’ own landing was not without danger, as his unit’s craft hit a mine on its way into the shore, blowing a hole in the ship’s landing door.

“That put us in water up to here,” he said motioning to his chin.

For those not as tall, the water was over their heads and Waters recalls helping at least one of his comrades ashore.

“It was hellish,” he said, describing the entire scene.

Waters thinks his immediate unit lost about six men on D-Day, but it eventually reached its objective, the village of Les-Buissons, where it stayed for what Waters estimates was several weeks.

“We had to man the trenches every night,” he said.

Before long the unit was on the move again, with its next target being Buron, a village located about six kilometres northwest of Caen, which was a key objective of the Normandy invasion.

The fighting was intense in and around Buron, Waters said.

In fact, newspaper reports in Kitchener, where Waters’ future wife Rhoda lived at the time, stated the Highland Light Infantry (HLI) was “wiped out” in the battle.

That was not the case, Waters noted, but the HLI did suffer heavy casualties in the battle (“bloody Buron,” as many HLI veterans call it), with the majority of the beds in a local hospital occupied by the regiment’s soldiers.

Some estimate the regiment suffered 262 casualties in the July, 1944 battle – about half of its assaulting force – with 200 wounded and 62 killed.

Among the wounded was Waters, who narrowly escaped death when a grenade exploded just steps away while he was walking alongside his corporal.

“It definitely killed him – he was a hell of a nice guy … all I got was shrapnel,” said Waters.

(It took three years to remove the largest pieces of shrapnel, which hit Waters in seven spots. He had surgery to remove another piece about six decades after the war ended, though he suspects all the pieces were never entirely removed.)

After recovering for several weeks in an English hospital, Waters made arrangements to visit his twin brother Mervin, who had also left home to volunteer for the war effort.

“It took me all day,” Waters said, noting he walked long distances and also hitched rides for a portion of the trek.

“When I got there I asked someone about him and they said they were all dead,” Waters said emotionally.

But like so many others who received such horrible news, Waters quickly rejoined his comrades in battle.

The regiment saw action during major battles in the Hochwald forest area in February and March, 1945, where Waters was shot in the groin. Once healed, he again rejoined his unit, which crossed the Rhine River in “water buffalo” landing crafts into the Netherlands.

“All I can say is the people there were starving,” Waters said of the Dutch population that was liberated by Canadian soldiers in early May, 1945.

“Our regimental unit put on a special dinner for the kids in a small village.”

While proud to have played a role in the Liberation of the Netherlands, Waters said he didn’t get to savour the moment like others did, because he had to perform communications duty and his unit quickly pushed through the area.

“When (the Allies and Germany) signed the peace agreement our unit was 20 miles into Germany,” he said.

Waters remembers vividly his colonel telling him to send out the “cease fire” message once the Germans surrendered.

“He was the first colonel I had ever hit,” Waters said with a chuckle, recounting how he slapped his superior on the back in celebration when he heard the good news.

But it took several days for things to completely settle down.

“The damn Germans were still firing,” Waters said of the confusion surrounding Victory in Europe (VE) Day, which is officially celebrated on May 8.

Waters was out of Germany in June or July and back to Ontario in the fall.

“I didn’t do anything for a while – except eat,” he said with a grin.

He worked for a year at J.M. Schneider in Kitchener before returning for good to the family farm in Wellington North. He married Rhoda in 1947 (they both still live on the property) and they had three kids: John, Patricia and Mervin.

Waters bred holsteins for decades before selling the farm in the 1970s. Looking back on a lifetime full of relationships and achievements, he says, “I know I couldn’t have done it without a family.”

He counts himself lucky for making it through the war, but he still deals with painful memories and flashbacks that have haunted him for the last 70 years.

“I have trouble going through the bad times – especially at night,” he said.

“It’s pretty hard to think of some of those guys that are gone before you, mainly because you knew them so well and had to bury them.”

He has returned twice to some of the WWII battle scenes, as well as various grave sites, which was difficult for him. Yet through it all, he doesn’t regret his role in the war.

“I enlisted at 17 … I think it ran in the family,” he said.

In the Great War his uncle Milton Sr. died in the Battle of Vimy Ridge and his father Alfred was wounded in the Battle of the Somme.

So Waters and his twin brother Mervin felt they should also do their part.

“It was just something we did,” he said.