ERIN – Not all exposures to active COVID-19 cases in educational settings or on school transportation are reported as soon as they could be, the Advertiser has found.

A social media user identified as Michael Smith in the “Erin Community Talk” Facebook group posted a message about receiving a late notification from Erin Public School about a potential COVID-19 exposure involving their child.

“So I just had an automated call about my kid having a potential exposure to [COVID-19] at school on [Oct. 4]. Would’ve been nice to know like 10 days ago,” stated Smith’s post, which was shared with the Advertiser from the closed Facebook group.

An edit to the post states: “It looks like the school was just notified today. Why did it take public health so long?”

Hillsburgh resident Michael Dehn reached out to the Advertiser with his own concerns about the situation after seeing the post.

Dehn explained his child, a Grade 1 student at Brisbane Public School, would normally share a school bus with Erin Public School students, possibly opening the door to exposure to the positive case from the Erin school, despite his child not going there.

Upper Grand District School Board communications manager Heather Loney confirmed “some buses” transport students from both schools.

For that reason, Dehn has gone out of his way since the pandemic began to drive his child to and from school in Brisbane to lessen the risk of exposure to the virus on school transportation.

“I mean there’s still a lot of people out there who don’t believe that COVID is a problem,” Dehn said.

A letter about the case, sent out to families and signed by Erin Public School principal Paul Huddleston, stated Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health (WDGPH) had notified the school that “an individual” had tested positive and the “individual was at school during their infectious period.”

Huddleston’s letter went on to state the individual’s 10-day infectious period had since passed, meaning there would be no isolation requirements.

“As a result, [WDGPH] has provided communication to the individual, with direction for them to go for testing and to continue monitoring for symptoms,” the letter stated.

“We would also ask that families continue to monitor your personal health and complete the self-screening tool each day before leaving for school.”

Loney told the Advertiser in an email, “the school and board were not notified by public health until the afternoon of [Oct. 18], which was after the date the case had been cleared by public health.”

When the school learned of the two-week-old case, notification was sent to families that same day, following protocol from WDGPH.

The principal collected contact tracing information and sent it to WDGPH. All staff and families were notified of the exposure through email and a robocall.

The notification and letter were posted online and WDGPH provided a letter to Huddleston recommending students in one class be tested and self-monitor for symptoms.

The case was not posted on the board’s website—only active cases are posted publicly, Loney explained.

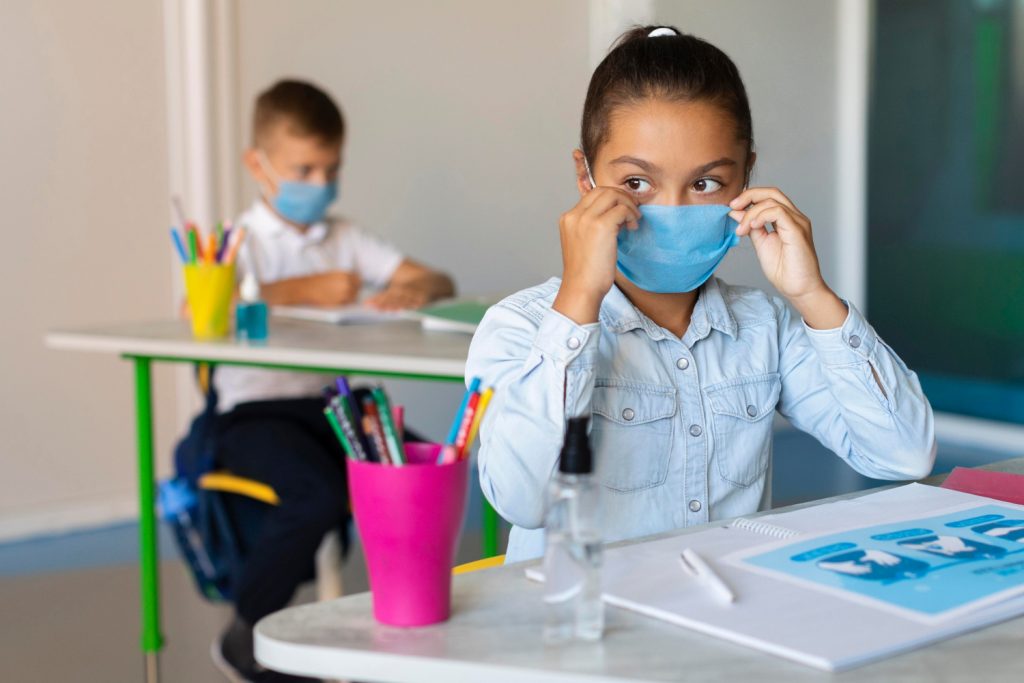

(Freepik image)

Loney was unable to say when, and for how long, the infected and symptomatic individual would have been exposing students, staff and their families to the virus, noting WDGPH doesn’t provide that information.

WDGPH spokesperson Danny Williamson stated in an email to the Advertiser the case “was tested very late in what would have been their … isolation period.”

In other words, because of late testing, the public health unit wasn’t aware of the case until after the infectious and coinciding isolation period had ended.

Williamson declined to provide more details about the specific case, citing privacy concerns.

Dehn takes issue with what he says is lack of communication from WDGPH about reasons for the delay.

“Unless the media reports, it doesn’t do the community any good when the answers aren’t published,” he stated in an email.

When public health units become aware of a positive test result, case management workers “move as quickly as possible” on tracing contacts, establishing when symptoms began (infectious periods are thought to begin two days before symptom onset, continuing for up to 10 days) and who the case has come in contact with during that time, Williamson explained.

“More than 95% of positive cases and high risk contacts are contacted by [WDGPH] within 24 hours,” Williamson stated, adding that statistic changes to 98% within 48 hours.

What public health cannot control, Williamson said, is “how long people wait to get tested after they start to experience symptoms.”

And people can test positive for the virus for up to three months outside of their infectious period because PCR testing picks up fragments of genetic material left behind in a person’s nose as the virus sheds.

“Our whole system of being able to really isolate cases, manage their contacts, get them isolated—depends upon quickly identifying those cases; the longer people wait, the more chance there is for COVID to spread,” said WDGPH associate medical officer of health Dr. Matthew Tenenbaum in a phone call with the Advertiser.

“It can be a bit of a punch in the gut to think about the fact that their kid was exposed ‘X’ days ago and they wouldn’t have even known until today; we recognize that source of frustration and tension.”

(Freepik image)

Tenenbaum added the “phenomenon” of late testing has been seen “a few times.”

Loney confirmed, as of Oct. 28, there has been three total UGDSB cases where notification to schools of an active case was delayed.

“In two of those cases, the individual was never present at school during the infectious period,” Loney stated in an email.

Wellington Catholic District School Board communications officer Ali Wilson said, in part, “We are not aware of situations where there has been a historical case,” responding to an Advertiser inquiry.

Wilson also mentioned cases are “no longer figured into our reporting” when students aren’t at school during their infectious period.

Tenenbaum said, “We do really want to critically protect schools … the importance of maintaining in-person learning is so important to the well-being of children.

“Even those people who are a bit COVID-measure-skeptical will acknowledge the importance of having their kids in school and if we have COVID being transmitted that makes it sometimes more challenging to keep schools operating well.”

He added the health unit is “trying to be creative” in getting people tested and is looking at “alternate ways of deploying testing that increases uptake and makes it more comfortable,” including saliva-based testing and take-home test kits.

Tenenbaum acknowledged even those who once followed public health measures are now fatigued, but he stressed keeping up measures in the “last leg of this journey” will put everyone in a better position for a return to normal.