By Jaime Myslik and Chris Daponte

ELORA – After four years, the calculation of Centre Wellington’s capital tax levy remains a source of confusion for some residents and a bone of contention among local councillors.

Yet all members of council seem to agree the levy has met its original goal of rebuilding crucial township infrastructure.

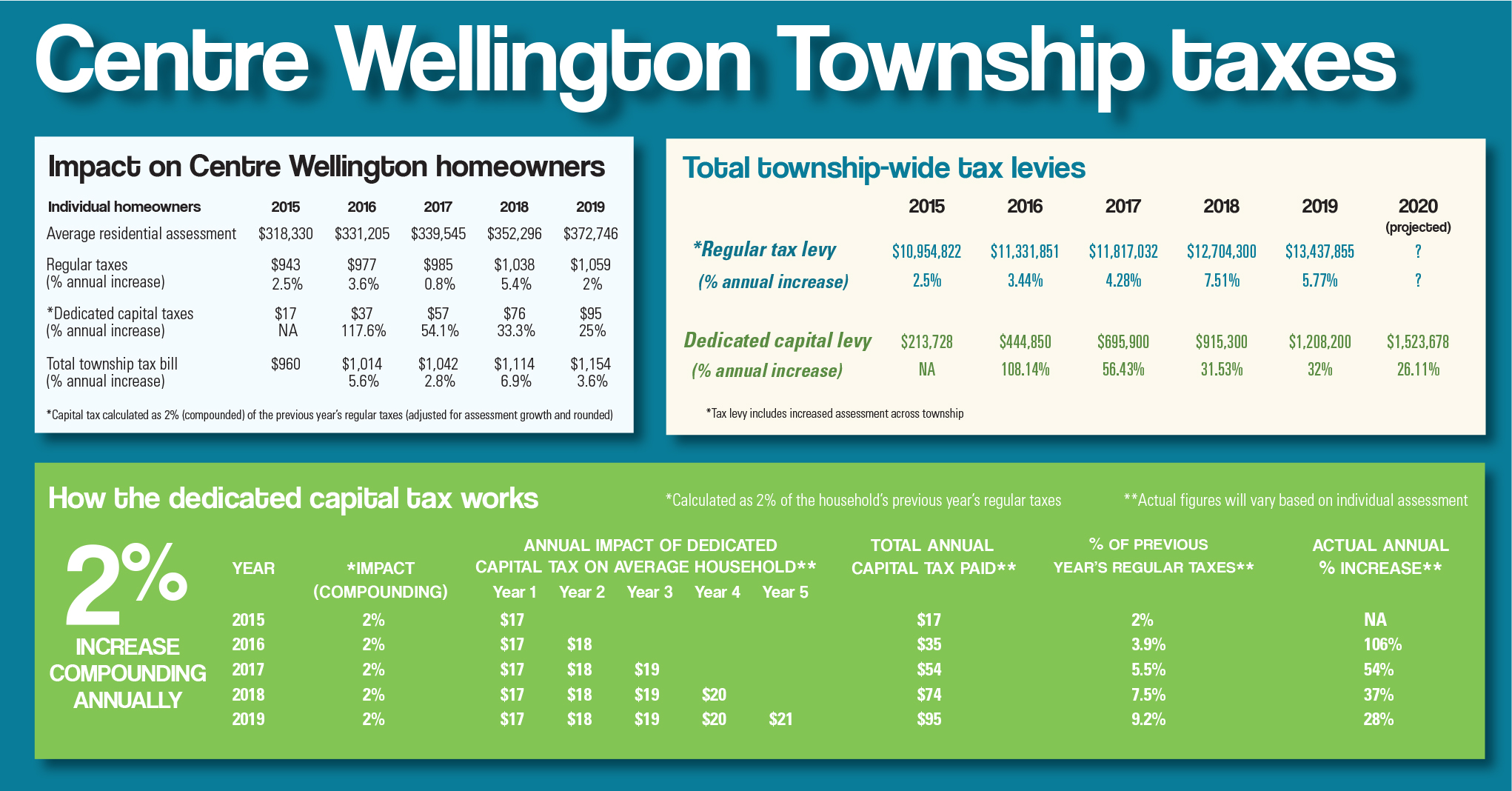

In 2015 Centre Wellington council adopted a 2% dedicated capital levy.

Compounding each year, the levy goes towards the repair and maintenance of bridges and culverts throughout the township.

For regular taxes, the municipality annually takes the total township tax levy – the amount of taxes to be raised to pay for items in the budget – and from that extrapolates tax increases for each homeowner.

The dedicated capital tax, however, works differently. It is set each year at 2% of the homeowners’ regular taxes the previous year (adjusted for assessment growth).

“We’re very much going at it backwards in this case because we know how much funding council is approving,” said Dan Wilson, managing director of corporate services.

“So we take that and decide what capital we’re going to do and in this case, the dedicated capital levy is exclusively for bridges and culverts.”

Mayor Kelly Linton said the dedicated capital tax levy was approved by council in 2015 “to make sure that it was very transparent and every single dollar that is put into that goes to high-priority bridges.”

Yet councillor Bob Foster said the township is “misleading” taxpayers every time it states the dedicated capital levy is 2%.

“It’s ridiculous. It’s mathematically false,” said Foster. “If you were in a Grade 12 math class, you’d get a big red ‘X’ …

“That’s the dumbest thing I’ve heard – and that’s coming from an accountant.”

How it works

The total amount raised township-wide by the dedicated capital levy is about $1.21 million this year.

The average homeowner with a residential property assessed at $372,746 would have paid $1,038 in regular tax in 2018 (adjusted for assessment growth). So the impact of the dedicated capital tax levy this year is $21 (2% of $1,038).

However, compounding over the last five years means the homeowner will actually pay $95 towards the capital levy this year ($17 for 2015, plus $18 for 2016, plus $19 for 2017, plus $20 for 2018, plus $21 for 2019).

Therefore, the 2019 dedicated capital tax of $95 is up 28% from $74 in 2018.

The totals paid by the average homeowner since the capital levy’s inception are:

– $17 in 2015;

– $35 in 2016 ($17 plus $18);

– $54 in 2017 ($35 plus 19);

– $74 in 2018 ($54 plus 20);

– $95 in 2019 ($74 plus $21).

Councillors disagree

Foster, who calls the levy a surtax, told the Advertiser the levy has “compounded to 9%.”

The average homeowner will pay $95 in dedicated capital tax this year, which is equivalent to 9.2% of the regular taxes paid in 2018 ($1,038).

“That’s kind of the way municipalities do capital levies,” Linton said.

He added, “A 2% capital levy increase is no different from any 2% increase; it’s always on top of what you increased the year before. So it’s completely consistent with how you measure any increase in taxation.”

Foster, who noted he has a master’s degree in finance and accounting, strongly disagrees.

“No one – and I repeat, no one – calculates it like this,” he said. “It’s not transparent, it’s false mathematics and it’s very misleading … you can not call this a 2% levy.”

However, councillor Steven VanLeeuwen agrees with Linton.

“The key aspect of that is that every single tax works that way,” he said. “If we did a 4% tax increase that’s 4% on the tax rate from last year.”

He said some people stumble on this idea.

“They go, ‘Well, it’s 2% on top of 2% on top of 2%,’” VanLeeuwen said. “That’s 100% right.”

It’s this calculation of the capital tax that most bothers Foster, who said it precludes establishment of the “comparability principle.”

“It misleads people about how the municipality is performing from year to year and compared to other municipalities,” he said.

Councillor Kirk McElwain agrees the dedicated capital levy can be misleading.

“I know staff have done their due diligence and other municipalities have brought in a levy, I just never agreed with it,” said McElwain. “It was never my favourite way of doing it, but we are getting some bridges fixed.”

McElwain has voted against the township budget each year since the capital levy was introduced in 2015. “I’ve disagreed from the start with that approach,” he said.

Councillor Stephen Kitras said referring to the capital levy as 2% “is a little bit deceptive.”

“The communication on it … should be that it’s a compounding levy,” Kitras said.

McElwain and Kitras both said the township should use funds it receives annually from the OLG (about $2.4 million in the last fiscal year) for bridges, as the township used to do, which would provide more flexibility.

McElwain explained that setting aside “2%” automatically for capital projects leaves the township with just a 2% regular increase to accomplish everything else – closer to 1% when wages are considered – because council will not want to exceed a 4% overall tax increase.

“We’ve tied our hands with some of the other projects we should be doing,” he said.

VanLeeuwen, however, said he likes that the capital levy “focuses any increase on the tax bill directly to bridges. It’s a very focused aspect of a tax, whereas if we did an across-the-board 4% tax increase, then you’re not 100% sure where those funds are going.”

Councillors Ian MacRae and Neil Dunsmore, elected for the first time last fall, said a compounding tax increases may be confusing for some, but the dedicated capital levy is a necessary evil.

“Maybe people don’t understand how it’s calculated, but at the end of the day, we need it to pay for the infrastructure issues,” said MacRae.

Dunsmore said during the election campaign people were “begging” to have bridges fixed – and most residents seemed okay with the 2% capital levy.

“There’s no other way – we’ve been abandoned by the province from the beginning and we have to fix our bridges,” he said.

Both MacRae and Dunsmore were strong supporters of a motion passed this year to have six additional 2020 budget meetings to better familiarize themselves with procedures.

When does the tax end?

Not long after first introducing the dedicated capital levy in 2015, township officials stated the plan was to end it by 2020. In 2016 officials stated increased provincial funding will allow the township to reduce the capital levy to 1% in 2021 and “eliminate” it in 2022.

That led many residents to believe they would thereafter pay nothing towards a dedicated capital levy, but that is not the case.

The township-wide dedicated capital levy is expected to reach just over $1.52 million next year – and will remain at that level in perpetuity.

“It’s there forever,” said McElwain.

What will be ended are the annual compounding 2% increases for homeowners.

Linton told the Advertiser at that point “we’ll go back to the way things were before.” Asked to clarify, Linton confirmed that once the 2% increases are removed, the capital tax levy is built into the tax rate going forward.

“It’s a stable source of funding,” he said.

VanLeeuwen added, “That’s the whole point of it.”

As of late March, Wilson could not state with certainly exactly when the capital tax increases will end.

“The way things are projecting, more than likely the 2020 budget will be the last increase,” Wilson said.

“It may trickle into 2021, but more than likely the last increase that council has approved will be done in 2020.”

Linton said the timeline to eliminate capital levy increases may change depending on provincial funding levels.

What is certain, he added, is the capital levy will continue to be a valuable source of funding to complete projects on the township’s 10-year bridge and culvert plan.

“This is just so that we have our own source of revenue to do what we need to do,” Linton said.

Foster said he is not opposed to collecting a dedicated capital tax, but “if we’re going to call it a 2% levy, it needs to be 2%…

“If it takes this long to explain … it’s obvious it’s mathematically false.”

Foster stressed he has no issues with past or current members of council who approved the dedicated capital levy.

“I have no axe to grind … I just want to be honest with people,” he said.

Wilson said Centre Wellington has over 100 bridges and culverts – “an unusually high amount” for a township with about 30,000 residents.

“[It] is a big burden

so we need this dedicated capital levy to make sure we’re not closing any more bridges, we’re trying to open them,” he said.

In the seven years prior to introducing the dedicated capital levy, only five township bridges were built or replaced, Linton said.

However, Centre Wellington is on track to complete 21 bridge projects in the seven years following the establishment of the tax in 2015.

Linton concluded that each new council has the ability to change policies during the budget process.