WELLINGTON COUNTY – At least 16 Ontario horses and donkeys have died of Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) so far this year.

That’s double the number of equines that died from the virus in the same time period in 2023, according to the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).

By the end of 2023, 18 equine cases were reported for that year. In 2022, no cases were reported, and a total of seven confirmed cases were reported in 2021.

EEEV, or triple E, is a mosquito-borne illness that causes brain and spinal cord inflammation, leading to a range of neurological symptoms, including incoordination, circling, decreased awareness, lethargy, fever, seizures, inability to stand, and blindness.

In equines, the virus has a fatality rate of about 90 per cent, according to the University of California Davis Centre for Equine Health.

“Once contracted, there is no treatment for [EEEV] in horses,” states an email to the Advertiser from OMAFRA officials.

Dr. Scott Weese, the director of the Centre for Public Health and Zoonoses and Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) professor, said it’s a challenging virus to manage because “it’s really rare, but really bad,” with infected horses often dying within a day of someone seeing signs.

Human cases

People can also contract EEEV, and in human cases the virus has a mortality rate of 50 to 75%, according to Public Health Canada.

“Death can occur within three to five days,” public health officials state.

Symptoms can include headaches, vomiting, respiratory symptoms, and dizziness, public health officials state.

On Sept. 12, Ottawa Public Health officials confirmed “an Ottawa resident who died of a viral encephalitis in August … tested positive for EEEV infection.”

This is the fourth confirmed case of EEEV in Ontario to date, according to public health officials, with the most recent previous case reported in 2022.

However EEEV is not designated as a “reportable” disease in Ontario, meaning occurrences do not need to be reported to public health.

“EEEV normally cycles between wild birds and mosquitoes, but can occasionally be spread to horses and rarely, to humans, through an infected mosquito’s bite,” Ottawa Public Health officials state. “Humans do not get infected with EEEV from a horse or another human.”

Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health (WDGPH) monitors mosquitoes for EEEV, and has not seen any cases in the region.

“The mosquito that primarily spreads [EEEV] is not as common to our region,” WDGPH associate medical officer of health Dr. Matthew Tenenbaum told the Advertiser. “They like swampy-type habitats which are rare in WDG.”

While horses are commonly vaccinated for EEEV, there is no current EEEV vaccine for humans. However Tenenbaum said “this is an area in which clinical trials are ongoing.

He said people can reduce their risk of contracting EEEV by taking steps to limit mosquito bites:

– wear light coloured clothing, including long sleeves and pants;

– use a mosquito repellent approved by Health Canada;

– repair holes in screen doors and windows; and

– remove standing water.

Equine cases

Drayton equine veterinarian Emma Webster said when horses get EEEV they “generally go down very quickly – within 24 to 48 hours.

“Initial signifiers, if identified, include fever, inappetence … dullness or lethargy,” she said.

These symptoms rapidly progress to neurological signs, she said, including incoordination (ataxia), circling, blindness and head pressing.

These are all “abnormal behaviours that we associate with a nervous system that is not functioning properly,” she noted.

Within a day or two, she said this will typically “progress to recumbency – the horse will go down and won’t be able to get up.”

Once the horse is down, she said seizures are common.

At this point, veterinarians often recommend euthanizing, as the fatality rate is high and “managing a down horse is very challenging,” she said.

“Horses are not animals that are made to lay down for any extended period of time,” she noted. “The longer a horse is down, even for 12 to 24 hours, the lower the chances the horse is going to get up again.

Vaccine – The majority of EEEV cases are in horses that are unvaccinated or under-vaccinated. Here, Drayton equine veterinarian Emma Webster prepares to give a horse a vaccine. Advertiser file photo

It’s also difficult to manage horses’ seizures, she added, as vets don’t have the ability to support them on site and horses may hurt themselves while seizing.

If transporting the horse to a 24/7 care facility with slings and lifting equipment such as the OVC in Guelph is not an option, Webster said that often leaves “a situation where that animal is suffering and we can’t control their discomfort and we can’t control their condition, so euthanasia is chosen … rather than letting that animal potentially die alone within the next 24 hours.”

The quick progression of the virus is part of the challenge, Webster said, as “there’s no way you are going to have test results and be able to confirm that diagnosis in 24 to 48 hours.

“I can take necessary samples like a blood test to send away to the lab,” but the results will take some time to come in.

“So in many cases the decision on how the animal is going to be treated has to be made before we know exactly what is going on,” she said.

Prevalence

Weese said the recent uptick in cases isn’t enough to make a conclusion about whether the prevalence of EEEV is increasing long-term.

“It’s really complex,” he said, with factors including how widespread the virus is in birds, and how widespread the populations of mosquito species that bite both birds and horses are.

“There are a lot of things at play,” he noted.

He said the variations seen from year to year are “probably just random variation – who knows why.

“It goes up and down,” he said, noting there was “another peak year” a few years back.

To make a conclusion about whether risk is really increasing, it’s the long-term trends that need to be analyzed, he said.

He also noted “there are probably more cases than we know of, that are not diagnosed. Not every horse that gets sick gets tested.”

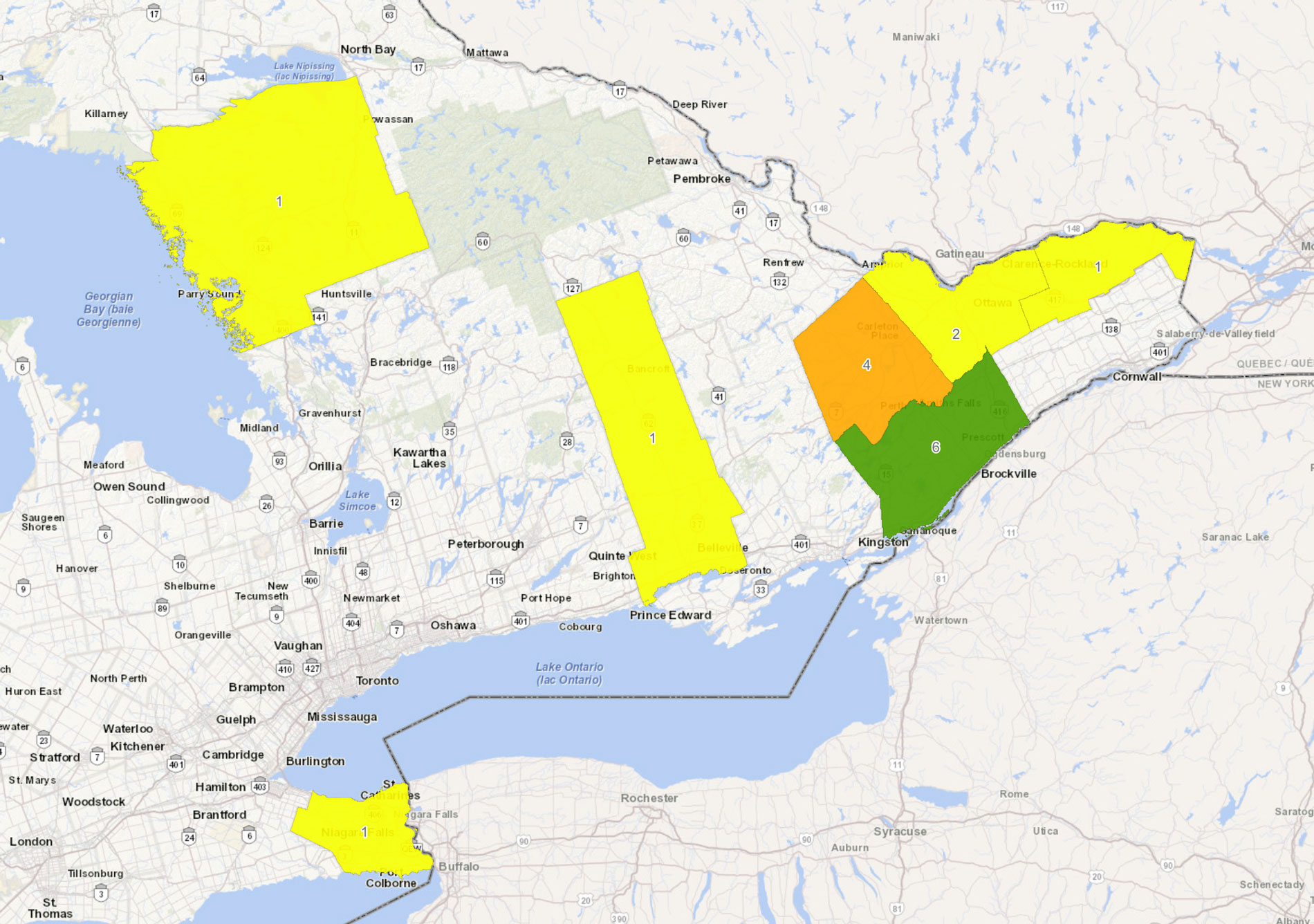

OMAFRA officials say EEEV outbreaks in Ontario “appear to occur in cycles, with larger outbreaks recurring in specific areas of the province such as in eastern Ontario, the Regional Municipality of Niagara and the District of Parry Sound for one to two years and then quieting down for several years in between.

“The reason for this is uncertain but likely depends on factors affecting mosquito and bird populations, such as climate,” OMAFRA officials state.

Webster said while she, thankfully, has not seen a horse with EEEV firsthand, she has heard that its prevalence in Ontario has increased significantly since she began practicing about 16 years ago.

Mosquitoes – EEEV is a mosquito-borne illness with a 90% fatality rate in horses. Pexels stock image

It’s most common in Eastern Ontario, with 13 of the province’s 16 EEEV cases reported in Lanark County, the United Counties of Leeds and Grenville, Ottawa, and the United Counties of Prescott and Russell.

The other three cases were in Niagara, Hastings, and Parry Sound.

The affected horses’ ages range from two to three months to 25 years.

In 2023, OMAFRA reported ten EEEV cases after Sept. 19, with the last case reported on Oct. 31, so Webster said she expects the year’s case numbers to continue to climb until well into the fall season.

Its not clear what’s causing the increased prevalence of EEEV this year, but Webster speculates that the mild winter could be a factor, “maybe not killing off as many mosquitoes as it has in previous years, so maybe more potential for spread of disease because of that,” she said.

Vaccination

The majority of EEEV cases reported to OMAFRA are in unvaccinated or under vaccinated horses, though two vaccinated fillies did die from the virus in August of this year.

According to OMAFRA, EEEV is “almost always fatal in unvaccinated horses.”

“My understanding is the vaccine does work reasonably well,” Webster said.

But she noted its “scary” to see vaccinated horses dying, as “We think of those vaccinated horses as covered.”

Weese agrees “as far as we know [the vaccine] is pretty effective,” but notes the rarity of the disease makes it challenging to understand how well the vaccine works in the field.

“Its definitely a useful vaccine,” he said.

Webster said most local veterinarians recommend horses receive an EEEV vaccine every spring, in addition to two when they are about five and six months old, and one about a month before a mare gives birth.

“Mares will then transfer passive immunity to foals through the placenta and milk,” Webster said.

For annual shots, vaccination is most effective if given in “April and June in our area, because that’s the onset of mosquito season for us,” Webster said. “If you boost vaccines in late spring, then they have the highest immunity level in summer and fall, when they are most likely to be exposed.

Mosquito management

Another way to reduce horses’ risk of EEEV is to manage mosquitoes.

This includes putting fly sheets on them, which Webster notes “will not stop every mosquito bite but will deter some.”

It can be beneficial to keep horses in the barn during dawn and dusk, only turning them out during the middle of the day when mosquitoes are less active, Webster said.

Avoiding trail riding around these times can also reduce risk, Weese added, particularly if trails go near areas with high mosquito populations such as wetlands.

“Inside the barn, people often have fans going,” Webster said, and the moving air deters mosquitoes and flies.

People can also reduce mosquito populations on their properties by removing breeding grounds such as standing water, she noted.

These measures are most important during August, September, and October, Weese noted, as that’s when EEEV cases are most common.