The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

Over the past few months I have spent some time gathering together my scattered notes on agricultural implement manufacturers in Wellington County. There were dozens of them over the years, but only a few had any major significance.

Belonging on the list of first-rank firms would be T.E. Bissell Co. of Elora, Ernst Bros. of Mount Forest, Beatty Bros. and Superior Barn Equipment, both of Fergus, and the Gilson Mfg. Co and Tolton Bros., both of Guelph.

Smaller and short-lived firms present problems for researchers. Few records beyond dates and names have survived for them, and it frequently is unclear what they manufactured. Typically, small manufacturers sold implements and machinery manufactured by others, with their own products being something of a sideline.

Of those items they built themselves, major components often came from outside sources. This was the case most often with plows, particularly after wrought iron and steel came into common use in the last third of the 19th century. Small factories, foundries, and blacksmith shops billing themselves as agricultural works invariably purchased iron or steel mold boards and plow shares, attaching them to wooden frames and then lettering them with their own names. In truth, these were assemblers rather than manufacturers.

Such small shops typified the farm implement industry in Wellington County in the 1850s and 1860s. They sold, repaired and modified tillage and harvesting equipment made in large part by others, and seldom employed more than three or four men.

By 1870, all the major towns and many of the crossroads hamlets in Wellington boasted a blacksmith who “manufactured” plows and other farm equipment. Among them could be listed Hugh Hamilton of Elora, Hugh Milloy of Erin, and Walton and Switzer of Clifford. There were dozens of others.

Firms on a larger scale began to appear in the late 1860s. Advances in metallurgy and technology required more expensive and better equipment, and the products themselves displayed better design and increased durability. Most of these new firms employed between 10 and 30 men, and the jobs themselves became specialized: machinists, foundry men, painters and assemblers. Though they continued to purchase components, and to do a great deal of assembly work rather than full manufacturing, these firms produced more of their own castings and forgings than the older small shops did.

Typical of these firms was that of Ash, Mair & Co. of Fergus (also known as the Ontario Foundry), established in 1868, and advertising a wide range of steam engines, machinery, farm implements, saws, stoves, and milling equipment as well as general foundry work.

The Harriston Agricultural Works, opened by Bob Lambert in 1869, advertised a narrower range than Ash, Mair & Co., but still an impressive one for a small firm: single and gang plows, straw cutters, cultivators and other tillage equipment, turnip cutters, and stoves. The firm’s own machine shop and foundry produced many of the components for these.

Two years later, Mitchell’s Champion Agricultural Works opened in Harriston. This firm produced and sold rakes, reapers, tillage equipment and plows, but achieved its greatest renown for its saws, for which its proprietor had secured patents as early as 1863.

Older than these was Isaac Modeland’s Irvine Foundry in Salem, which began production in the fall of 1864, producing plows, tillage equipment, and threshing machines. Modeland leased the factory in 1878 to Archibald Filshie, who later established what became the Ernst Bros. business in Mount Forest.

Unlike the small shops and blacksmiths, Modeland, Mitchell, Lambert and the others of the same group of manufacturers promoted their products, invariably employing the most boastful language possible, in an effort to expand their market beyond their immediate neighbourhoods. They showed their implements at fairs, and competed against one another at plowing matches and demonstrations.

The farm implement factories established in the late 1860s and early 1870s had financial requirements far higher than most proprietors could provide. To alleviate this problem, a group of Guelph businessmen formed a joint stock company in the fall of 1870 to back and finance a new farm implement factory for Levi Cossitt, who already operated a foundry in the city, producing farm implements on a modest scale. Interestingly, the group included the owners of three other foundries in Guelph. Presumably, they saw a role for themselves in providing castings and other components for the proposed Guelph Agricultural Works.

The new Cossitt plant, located on the corner of Norfolk and Quebec Streets across from the present Guelph library, was soon producing an impressive range of plows, seed drills, rakes, and fanning mills.

The example of the Guelph joint stock company inspired a similar venture in Elora, where a group of the village’s businessmen formed a joint stock company in 1873 to take over and expand David Potter’s foundry, adding threshing machines to the modest lines of plows and cultivators Potter already produced. The Elora Agricultural Machine Company, financed by stock subscriptions and a loan from the village, soon had 60 men on the payroll, making it by far Elora’s largest employer.

In the long run, though, neither the Guelph nor Elora firms enjoyed long-term prosperity. Cossitt never managed to build up a strong customer base, and he was further set back when the plant burned down in 1877. It was rebuilt, but Thomas Gowdy, another foundry man, took over the business in 1882.

In Elora, the Elora Agricultural Machine Co. enjoyed an even shorter life, suffering from the beginning from financial mismanagement and excessive inventory. David Potter eventually took it over himself. By then it had become largely a repair shop.

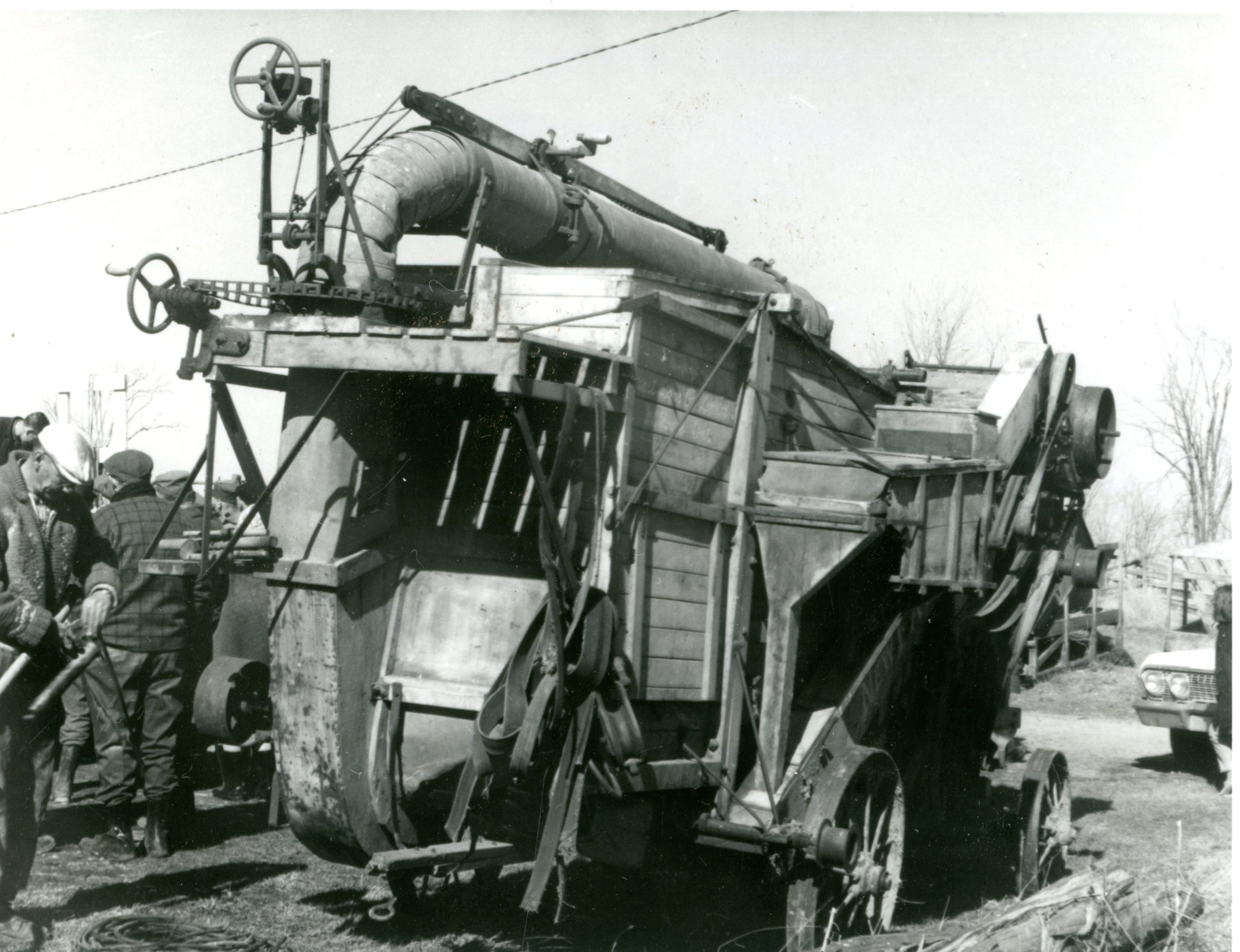

The farm implement manufacturers of the late 1860s and earl 1870s invariably tried to produce a wide range of products, though some specialized to an extent in either tillage or harvesting equipment. Their heyday lasted until the 1900 era, though they were beset constantly by competitive pressures from specialized manufactures, and from the rapidly growing Massey-Harris firm, which by the 1890s produced a full range of farm equipment, distributed through an extensive dealership network.

Other than plows, few of the products of these firms have survived, and there seem to be scant remaining production records for them. It is quite likely that they produced only small numbers of most of their advertised implements.

The Wellington County farm implement firms best remembered today are those established in the years immediately before and after 1900. Unlike those of the previous generation, the new firms specialized in only one or two products. Their plants had more and better equipment, and the amount of working capital employed by them far outstripped the older firms.

A couple of the new firms had older roots. In Fergus, the Beatty Bros. firm, which had featured a full line of tillage equipment, went through a bankruptcy in 1896. The new firm concentrated on barn stabling and manure handling equipment. In Guelph, Tolton Bros., established in 1866, abandoned many lines, making a specialty of pea harvesters and plows. In Mount Forest, Ernst Bros. took over a factory and foundry that dated to 1859, but by 1910 the plant was concentrating almost exclusively on “The Favorite” threshing machine.

The half-dozen or so Wellington firms producing farm machinery in the 20th century managed to compete more or less successfully against larger companies for decades, all building markets far beyond the borders of the county. This was a remarkable feat in a period when the entire farm implement industry was going through major consolidations that eliminated virtually all small manufacturers. Names such as Ernst, Bissell, Beatty, Tolton, and Gilson will always remain an important part of our local agricultural heritage.

Next week: Implement manufacturers in the 20th century.

*This column was originally published in the Wellington Advertiser on July 14, 2000.