The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

With the instantaneous communications available to us today — telephones, fax, modems, cellular networks — in addition to the post office and courier services, it is hard to imagine what it was like before there were communications services of any kind.

But this was the situation in central Wellington before 1836, when postal authorities decided to open a post office at Fergus. It was the second post office in present-day Wellington County. The Guelph office was opened eight years earlier.

In the early 19th century, the British government controlled the Canadian post office, and the British viewed it as a money making proposition to offset losses incurred in military and administrative expenditures in Canada.

The postal network of Upper Canada was limited to a small handful of routes connecting the largest centres, and it lagged far behind the settlement of new areas such as Nichol, Garafraxa and Eramosa townships.

Rates, based on distance, were prohibitively expensive. Not surprisingly, the quality of the postal service became a major political issue during the 1820s.

Complaints declined in quantity and vehemence with the appointment of Thomas Stayner as deputy postmaster general in 1827. Stayner answered to the British postmaster general, but he quickly gained support in Upper Canada by extending and improving the service.

Guelph was the first new office he opened. By the time he authorized the Fergus post office in 1836, he had more than tripled the number of post offices in Canada.

Stayner kept the confidence of the British authorities through sound management practices. He opened offices only where there was a real need for them, and he chose his postmasters carefully. Increasing revenues more than made up for the extra costs of the expanded system.

James McQueen, Stayner’s choice for postmaster at Fergus, is a good example of the type of man he sought for the postal service. McQueen was a graduate of Glasgow University, and might have lived a quiet and comfortable life in the old country, but he and his wife, Christina, chose instead to emigrate to the United States in 1834. Disliking the atmosphere there, he moved to Halton county, where he taught school.

Early in 1836, McQueen came to Fergus. He soon had two jobs: not only was he appointed postmaster, but he was also hired as the schoolmaster for the village’s one-room log school, located on the site of the current Fergus school that bears McQueen’s name.

At the beginning of 1837, when township government was established in Nichol, McQueen acquired additional responsibilities when he was appointed clerk and treasurer.

It is a certainty that McQueen’s clerical ability and intelligence were known to prominent people in Fergus before he arrived. Oral tradition links his appointments with lobbying by James Webster, A.D. Ferrier, and Adam Ferguson, the key figures associated with Fergus in its early years.

To the modern observer, it would appear that McQueen had undertaken an impossible work load, but in the conditions of the 1830s, this was not the case. High postage rates continued to hamper mail volumes, and in the 1830s Fergus had only twice-weekly service. Weekly mail volumes rarely exceeded a few dozen letters and newspapers.

This was an era of extremely limited government, and McQueen’s township duties required only a few hours per month. School teaching involved few administrative duties beyond the classroom. McQueen had time left over to clear a farm and to work as a volunteer in church and community projects.

Mail volumes grew through the 1840s, but still were comparatively light. McQueen operated the post-office from his house until 1848, when increasing usage and changes in transportation prompted an office on St. Andrew Street.

Mail had originally been brought to Fergus by way of Elora, by a man on horseback, or sometimes on foot. In the early 1840s, a stagecoach followed the same route. By 1847, this service was daily, and in that year Stayner authorized a new tri-weekly stage route to Owen Sound, serving a series of new offices along the way.

Many residents and all businessman now visited the post office daily, and it was necessary for it to be located in the midst of the business sector of the village.

In 1857, McQueen relinquished his position as schoolmaster in order to devote more attention to the post office and his township responsibilities.

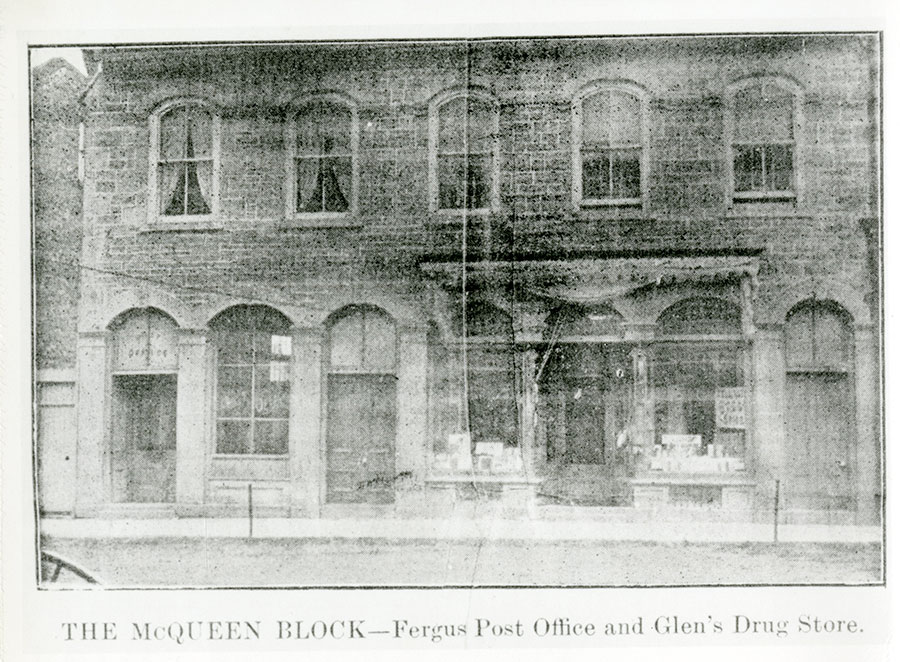

McQueen later built a fine stone block on St. Andrew Street to house the post-office and a store. It still stands, though few now refer to it as the McQueen Block. The post office remained at this location until the current post office was constructed in 1912.

Mail volumes expanded greatly after 1851, when Canada took over control of the service. The mileage-based rates were replaced by a single flat rate, effectively reducing the cost per letter by 33% to 80%, depending on distance.

As well, new post offices in small hamlets and crossroads communities were added to the system after 1851. There was a further 40% reduction in postage rates when the Dominion of Canada post office began operation in 1868.

By 1870, the outgoing mail at Fergus passed the 1,000-letters-per-week level, with a larger level of incoming mail. Mail for the smaller offices in the area increased the workload. There were also money orders to sell and redeem.

In 1871, the Fergus post-office was designated a savings bank office, allowing residents to deposit small amounts in savings accounts. Few banks at the time offered savings accounts.

McQueen’s salary, based on the dollar volume of business at the office, varied between $500 and $600 per year in the 1870s. Out of this he was responsible for hiring necessary help and maintaining the office. In order to make an adequate living, postmasters such as McQueen had to have other sources of income.

During the 1870s, most of the actual work at the post-office was performed by his daughter Christina, while McQueen concentrated on his township duties and his farm in Nichol township.

Christina McQueen formally took over the position of postmaster in 1882, retaining the position for the next 40 years.

James McQueen continued as clerk and treasurer of Nichol township until 1892. He died in 1899, at the age of 89, having served the community for 63 years in a variety of official and voluntary roles.

*This column was originally published in the Elora Sentinel on March 30, 1993.