The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

The local option vote is unfamiliar to most people 40 or younger.

Those were plebiscites held in a municipality to decide whether liquor could be sold within the municipal boundaries. Voters could voice their approval or disapproval of beer parlours, cocktail lounges, licenced dining rooms, beer stores, liquor stores, or any combination thereof.

The Ontario government ended prohibition in 1927 with the promise that every municipality would be able to decide its status. Over the following four decades, liquor votes were a common part of the political landscape, until very few dry areas remained.

In Wellington County at least, most of the campaigns featured a well organized anti-liquor campaign. Usually, no one was willing to come out strongly for the “yes” side. A notable exception was the vote held in Erin in June 1954.

It all started innocently enough. At the inaugural council meeting of 1954, Reeve D.S. Leitch presented his colleagues with a six-item agenda of goals for 1954: a new high school, a housing program in cooperation with a mortgage company, a motor vehicle licence bureau, a combined liquor and beer store, a $200 budget to promote Erin, and the widening of a portion of Main Street.

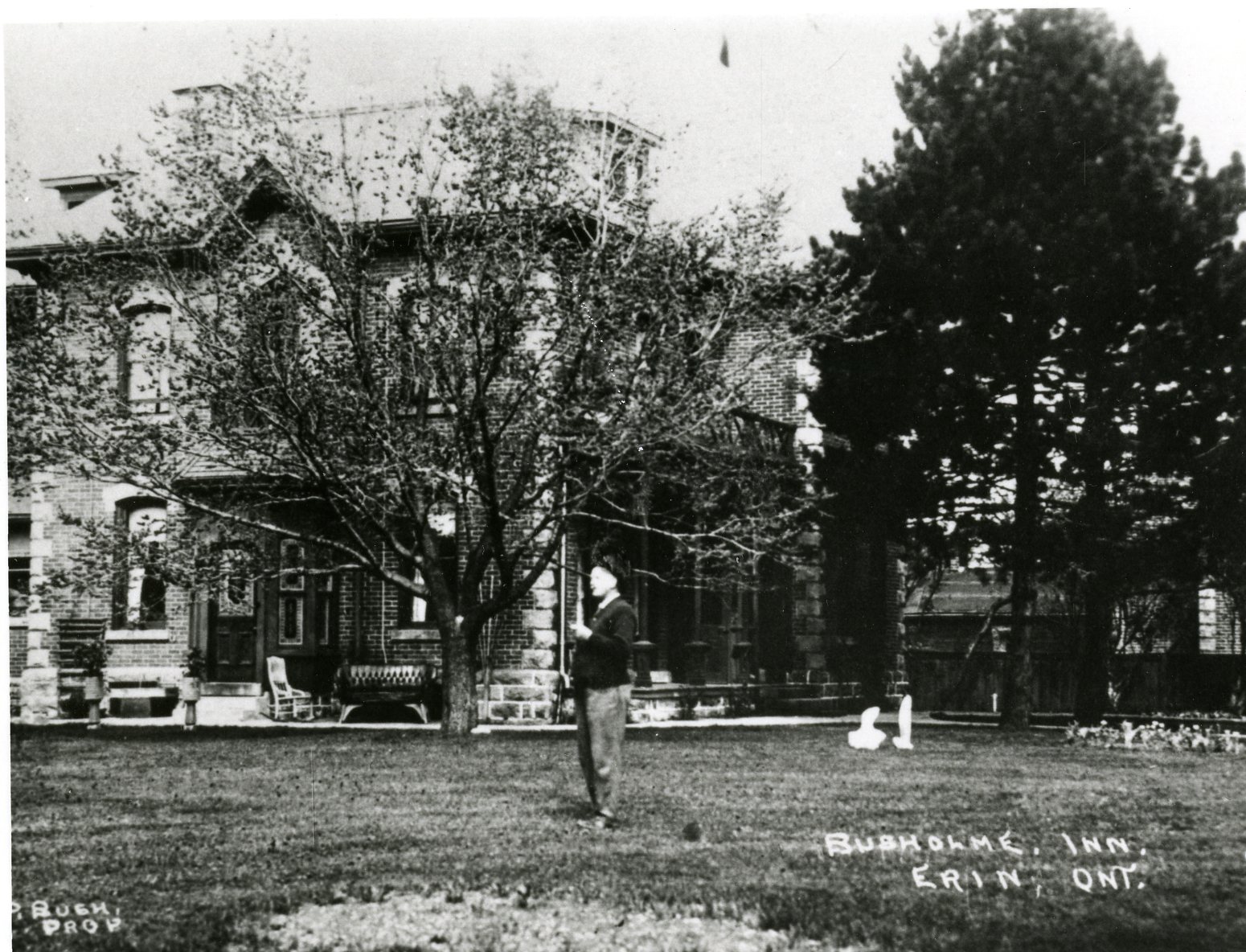

Altogether, it was the sort of list that a progressive small-town council in the 1950s would pursue to boost its economic vitality. Instead, Reeve Leitch provoked a chorus of outrage from a small but vocal group of ratepayers. The group organized before the end of January to put a stop to any talk of a liquor store in Erin. Then they went a step further: they decided to try to shut down the Busholme Inn, Erin’s last remaining hotel, which had operated a licenced beverage room since the early 1930s. (The Busholme Inn is now the location of Rob Roy’s Pub and Restaurant.)

Seizing the initiative, the anti-liquor group presented a petition to council on Feb. 4, requesting a vote on beverage rooms.

Clare Young, the Busholme’s manager, appeared at council, pleading that the petition be ignored. According to the regulations, though, council could do little if the petition seemed in order. They had to forward it to the Liquor Control Board for the setting of a date for a vote.

Word soon came back. The reeve announced on Feb. 22 that the vote would be held on June 23. By then the campaign against the Busholme was already on, and would continue for five full months. This would be the third liquor vote in Erin since the end of prohibition. Erin’s voters had supported hotel licences on both previous occasions.

Only rarely did local newspapers become involved in local option campaigns. Editors did not want to antagonize a sizeable portion of their subscribers by taking a stand. Such was definitely not the case with the Erin vote. Publisher R.W. Hull of the Erin Advocate and his family came out in favour of the Busholme before the petition even got to council. Subsequently, the paper became even more outspoken in its support of liquor sales in Erin.

They did not publish editorials at that time, but the Hulls never hesitated to insert an opinion in a story if they deemed it appropriate. Extended opinion appeared in a column credited to “The Periscope,” perhaps penned by the elder Hull. The column came out swinging against the local option in the Feb. 25 issue: “Experience has proven that the local option is totally unsuitable and the brainchild of a bygone era which brought into being a scattered nest of bootleggers and blind pigs … whoever is responsible for the return of the local option, suffers loss of memory or senility of mind, if they can recall any virtues in its operation.”

The “dry” committee had not expected that sort of rhetoric from any quarter. More important, the amount of support for the Advocate’s position, especially among Erin’s business community, showed that the effort to revoke the Busholme’s licence would be a tough one to achieve. Some people believed that the whole matter had been brought up by Reeve Leitch’s opponents to harass and embarrass him. Several who signed the petition requesting a vote later claimed that they had been misled, and had been told they would be voting on the liquor store question. They did not realize that a vote would be required in any case before a liquor or beer store could open in Erin.

An anomaly of the campaign was the absence of Erin’s protestant churches in the “dry” campaign. Typically, an uneasy and very temporary alliance of bootleggers, ministers, taxi drivers (who did a steady business delivering liquor from out of town), and temperance women dominated anti-liquor committees. As the dry campaign developed, it appeared that its strength came from those who had personal issues with either the reeve or Clare Young of the Busholme Inn.

“The Periscope,” meanwhile, returned to the subject nine more times, reaching new heights of grandiloquence: “As one who has lived and observed the intricacies of this infamous measure through the years, may you know that Local Option is only the illegitimate offspring of a politician, reared to exploit the ignorance of the rural population of those times. Conceived, born, lived and died in robes of iniquity,” he wrote for the April 1 issue.

A hint of the language of the King James Bible had crept into “The Periscope’s” paragraphs by then, and he began to argue that a true Christian could never support the local option: the concept showed disrespect to fellow man, and the political campaigns invariably produced animosity and bitterness of a profoundly unchristian nature.

In late March, Bill Hayes, a Georgetown bootlegger, sold a bottle of whisky to a 15-year-old Erin boy, who promptly guzzled it, then fell unconscious in a snow bank. He had to be rushed to Toronto General Hospital for treatment. Hayes received a two-month stay in the hoosegow. Both sides in the campaign saw a lesson in the incident to support their cause.

Surprisingly, the campaign died down in April, and never reached the heights of bitterness and animosity that many residents feared.

An unfortunate victim of the campaign was W. Gray Rivers, president of the Ontario Temperance Society. He had spoken to the Erin Businessmen’s Association before the liquor question emerged, and had told his audience that he found the Busholme to be well run and “would not advocate any change.” He later organized the campaign for the anti-liquor campaign.

The pro-liquor group, calling itself the Committee for Legal Control, used that quotation in their publicity. The dry side, meanwhile, quoted other sections of Rivers’ Erin address. Rivers himself jumped in to clarify his position, but only made things worse for himself. He found himself in trouble within his provincial temperance organization, which led to adverse publicity in the Toronto dailies.

By June everything that could be said about the local option had been uttered at least once. Both sides continued their campaign, mostly by personal contact. Whether or not by divine intervention, the leader of the pro-liquor group was felled at the end of May. Clare Young climbed onto a chair to fix a blind at the Busholme, fell and fractured his arm.

Two weeks before the vote, 48 of Erin’s businessmen signed a letter in support of a hotel licence in Erin. A week later, the Committee for Legal Control placed an advertisement in the Advocate. It claimed that the hotel was vital to Erin’s economy, and was worth almost $25,000 a year to the village.

Voting day brought out 518 of Erin’s 557 qualified voters, a 93% participation rate, far higher than in regular elections. About 65% supported the wet side. The ballot had contained three separate questions, and totals varied slightly: 309 supported a licenced dining room, 305 a men’s beverage room, and 295 a ladies’ beverage room. Interestingly, there were 53 spoiled ballots.

With the votes counted, Clare Young could afford to be magnanimous. He congratulated W.G. Rivers for the “clean-cut fashion” in which Rivers had run the dry campaign.

Erin had to wait for its liquor store, the concept that had provoked the campaign, and had been forgotten in the debate over a hotel that operated under licence for 20 years. Reeve Leitch had long stroked that item off his list of 1954 projects, but he did make headway with most of the others.

*This column was originally published in the Wellington Advertiser on May 7, 2004.