WELLINGTON COUNTY – Dale Wideman sped in the opposite direction he had just come from, steering a van along Route Nationale 8 in Haiti, attempting to evade a pursuing pickup truck full of heavily armed men.

The pickup truck quickly gained on the van, sped ahead and locked the brakes, forcing Wideman to bring the van to a halting stop.

Several men swarmed the van, yelling excitedly in Creole, the barrels of assault rifles staring down Wideman and 16 fellow passengers inside, including five men, six women and five children aged 10 months to 15 years old.

I: Haiti

On Oct. 16, 2021, the first frost had already fallen over Wellington County, but 5,000 kilometres away in Haiti, it was a balmy 32 degrees Celsius.

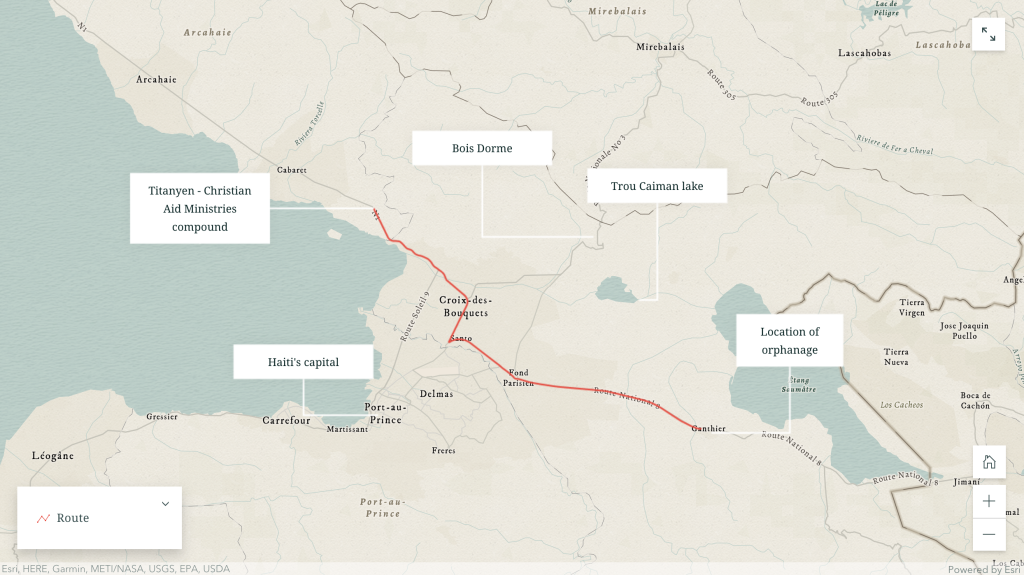

A group of Christian Aid Ministries (CAM) missionaries, consisting of men, women and children of all ages, wanted off the CAM compound to visit a nearby orphanage in Ganthier.

“We decided to make it a kind of a day trip … most of the compound wanted to go basically to just get out into the Haitian culture a little bit as a group,” Wideman recalled in an interview with the Advertiser.

His assignment was to collect photos and updated information for sponsors of around 20 orphaned children being cared for there.

At the time, Wideman was about two-and-a-half months into a two-year commitment with the Ohio-based missions organization, that allows “Amish, Mennonite, and other conservative Anabaptist groups and individuals” to bring the gospel to a “lost and dying world” through the provision of aid, according CAM’s website.

The Haitian countryside seen from Titanyen. (Photo by Dale Wideman)

Growing up, Wideman enjoyed reading stories of missionaries and their adventures, and said as a Christian, he is taught to serve and help where able, and to share the word of God.

It wasn’t the first time the 24-year-old had ventured away from a predictable upbringing in northern Wellington County to embark on trips to far-away places.

“I always had an interest in mission work,” he said.

Haiti was fourth on his list, with previous mission trips to Liberia, Grenada and Puerto Rico.

Weeks before Wideman arrived, Haiti’s president Jovenel Moïse was assassinated on July 7.

“I did know about the unrest, I mean to a certain extent, Haiti’s kind of always like that, but it didn’t really alarm me,” Wideman said, pointing out many American staff members at the compound had been residing in the country for several years.

According to an annual CAM report, Haiti’s political unrest caused the organization to remove its American staff, who returned in 2020 following a nine-month absence.

Wideman arrived in the Haitian coastal village of Titanyen on July 24, with little more than some clothing and a smartphone.

His role was to assemble food orders and pharmaceuticals at the compound’s warehouse for distribution to local residents and clinics throughout the country.

A Haitian women accepts a Christian Aid Ministries food box in Montrouis, a coastal, tourist beach destination in the department of Arttibonite, south of Saint-Marc. (Photo by Dale Wideman)

Trucks were loaded with food boxes arriving in sea containers from CAM’s Pennsylvania warehouse, containing rice, cooking oil, dry vegetable soup, sugar and salt.

Wideman lived on the compound, on the top floor of a three-storey building with two other men, Wes Yoder and Sam Stoltzfus, spending most of his days within the compound’s walls with access to clean drinking water from a drilled well and plates of rice, beans and pasta, prepared by Haitian cooks.

The group of missionaries, from Mennonite and Anabaptist communities in Michigan, Ontario, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Wisconsin and Oregon, lived, worked and socialized together.

Four days a month, Wideman jumped in a truck with an interpreter and took to the Haitian countryside to check on CAM-supported medical clinics. Beyond the compound’s relative safety, he came face-to-face with the stark poverty afflicting millions of Haitians.

“As soon as you step outside then it was a third-world country,” Wideman said.

Haiti is home to few paved roads; many are plagued by massive potholes and high traffic, especially in centralized urban areas, like the capital of Port-au-Prince.

Many drive dilapidated vehicles and there’s little order or rules of the road. Navigating the country becomes an exercise in patience, according to Wideman. A drive to Haiti’s northern coast from the Titanyen could take upwards of eight hours, and six heading south.

Traffic and daily life along Route Nationale 2 in Haiti’s capital of Port-au-Prince. (Photo by Dale Wideman)

And yet, “I was starting to really enjoy it,” the self-described introvert said of his work, having overcome an awkward first month settling in.

It wasn’t long before rumours of the country’s notorious gangs began to materialize before Wideman.

A symptom of a people long backed into a corner and oppressed by foreign economic control, coups and corrupt politicians, the gangs have become commonplace in Haiti, controlling portions of the country, key roadways and fuel distribution.

“I think some gangs do maybe pressure the government for reform … but it’s very easy for them to cut off supply,” Wideman said.

Gangsters take advantage of the haphazard road network, using traffic congestion to their advantage, at times abducting people from stopped vehicles.

According to the Center for Analysis and Research in Human Rights in Port-au-Prince, there were at least 782 kidnappings in Haiti between Jan. 1 and Oct. 16 last year, of which 221 occurred between July and September alone. Of those kidnappings, at least 53 people were from four different countries outside of Haiti.

Jason Kung, a spokesperson for Global Affairs Canada, told the Advertiser the department would not disclose the number of Canadians who have been abducted in Haiti in past years because “low numbers for certain years” could lead to “the possibility that individuals could be identified.”

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs stated in a June report last year that “an estimated 13,600 people” that month fled the nation’s capital to escape gang violence.

In April of 2021, Catholic priests, nuns and family members were abducted, reportedly by the same gang that later abducted Wideman, before being released unharmed.

And in June, Doctors Without Borders temporarily closed an emergency centre in the Martissant commune of Port-au-Prince after its ambulance staff and drivers were robbed and threatened with weapons.

“We were well aware there were gangs around, but we had our work to do,” Wideman said.

The first gangsters he saw carried assault rifles, and others in a group of younger men wore balaclavas, making hand motions and gestures signalling guns as a warning to those in their territory.

“I wasn’t really told a lot … basically not to be too alarmed by them,” he said. “Nobody [had] got hurt or anything up to that point.”

Three weeks later, that would all change.

II: Panic

On the morning of Oct. 16, the passenger van left the compound destined for Ganthier.

Five children and 12 missionaries were packed in the van for the ride out of Titanyen, through Port-au-Prince and eastward onto Route Nationale 8.

Wideman drove with Yoder in the front passenger seat and a six-year-old child sandwiched between them.

The van passed through a checkpoint, marked by scorched tires, outside of the capital city outskirts and arrived 90 minutes later at the orphanage in Ganthier.

A map illustrates the route Christian Aid Ministries staff took from the village of Titanyen to arrive at an orphanage in Ganthier and other relevant landmarks. (ArcGIS map)

“We had a really nice time there, it was a very well-run, organized, clean orphanage, and children were happy and fairly well mannered,” Wideman said.

Some of the guys kicked around a soccer ball with children shy of the missionaries, and orphanage staff treated the group to dishes of fried chicken, plantain and french fries served with cola.

At 1pm, the group piled back into the van and aimed toward the renowned Village de Noailles, or the Iron Village Artisans, located in the Croix-des-Bouquets neighbourhood, where artworks are fashioned from metal and sold as souvenirs.

About 10 minutes outside of Ganthier, on Route Nationale 8, one of Haiti’s well-kept arterial roads leading in and out of the neighbouring Dominican Republic, the group saw a box truck was parked diagonally across the highway.

“To see vehicles parked at weird angles is nothing unusual in Haiti, and people on the roads,” Wideman said.

As they neared to within a couple hundred feet, Wideman could see men holding guns and spun the van back in the opposite direction.

“We kind of thought that was close, but we’re gonna be fine,” Wideman said.

But as they attempted to drive away, a pickup truck caught up.

“There was a lot of action at once,” Wideman said.

“There was one moment for like a couple seconds I could almost feel myself panic, my leg was just jerking back and forth and I couldn’t control it for a bit.”

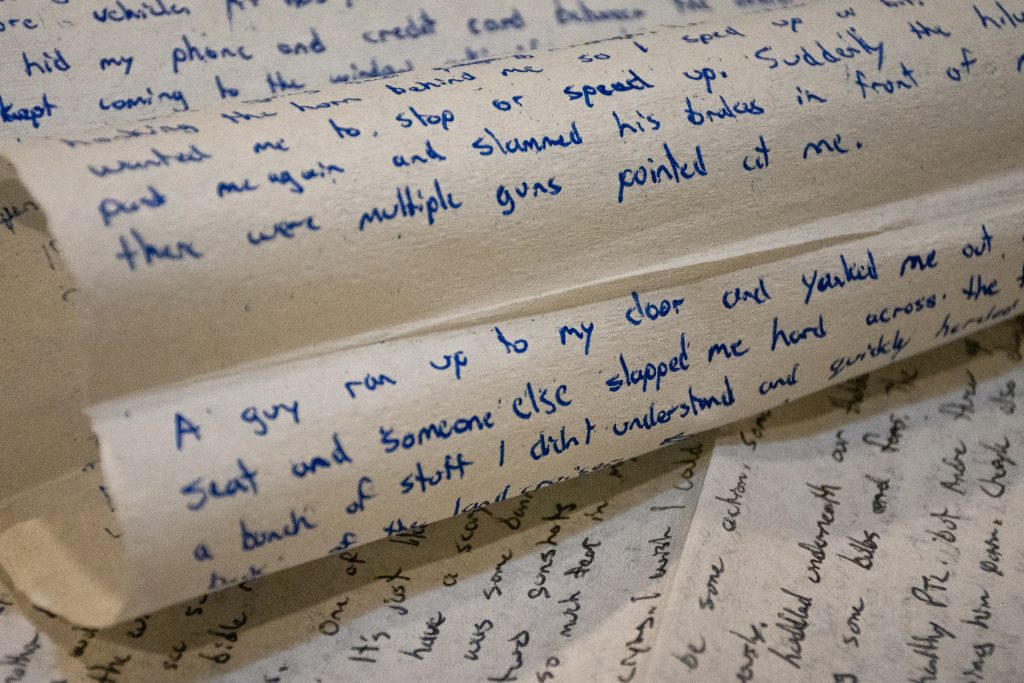

Words written by Dale Wideman on papertowel diary while he was held in captivity in Haiti in 2021. (Jordan Snobelen photo)

The gangsters told Wideman turn the van around and follow the box truck parked across the highway.

“After they had got us and they hadn’t shot us right away … I was just really hoping that they’re just going to rob us,” he said.

But they were directed off the main road onto one of the many narrow, dirt offshoots travelling north. Wideman’s heart sank.

“I didn’t know what was going to happen,” he said.

The convoy stopped and the van’s door was pulled open, followed by demands for guns and cellphones.

The group of missionaries had no guns to surrender and some of the men acted ignorant of their only source of communication with the outside world. Wideman stuffed his cellphone between the seat.

The van driven by Dale Wideman. (Photo by Dale Wideman)

Now hightailing down the sideroad, Wideman fell behind.

Once again a pickup truck overtook the slower-moving van, locking up its brakes.

Wideman was ripped from the driver seat, replaced by one of the gangsters, and stuffed into the back of an SUV with a command to stay down.

“That was a little scary, but I think the group in the van was more scared for my life; they thought they had seen the last of me,” Wideman said.

“I just had images of them pulling all the people out of the bus and lining them up and executing them.”

According to Wideman, someone in the van had managed to send a text message and even drop a location pin on Google Maps.

Around two hours later, the caravan came to a final stop at a property surrounded by thorn bushes and trash where Wideman was reunited with the other missionaries.

Upwards of 20 men armed with assault rifles guarded the area.

On the property were two buildings, one of which was called “The Devil’s House,” where the missionaries were lined up, recorded on video, and told it was the last anyone would see of them.

Sure looked like a good spot for them to execute us, Wideman thought.

That the entire group had been abducted never occurred to Wideman until he found himself stuffed into a stifling, smelly, 10-foot by 12-foot room with the rest of the group, in a small building across from the Devil’s House.

“I struggled a bit because I was the driver and I had sort of planned this thing, so I felt pretty guilty, just seeing the children and this 50-year-old lady in this group, I just felt terrible,” Wideman said.

Despite being held captive without any idea of what was to come, an odd sense of peace and safety settled over the reunited group.

III: Demands

At around 5:30pm the same day, the phone rang at the Wideman household in Wellington County.

Doris, Wideman’s mother, was told little else beyond the news that Dale had been abducted along with other CAM staff and that a ransom was being demanded.

“That’s pretty much all he could say,” Doris said of the initial phone call.

Doris felt light-headed and had to sit, relaying the news to her husband, and Dale’s father, Ken.

They sat in silence digesting the news and began reaching out to their other children who were already hearing word of the abduction.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) reached out to Doris and Ken days later and sat down with the couple to gather information about their son and his cellphone account.

The feds provided a binder with questions of things to say if they received a phone call from Dale’s captors, Doris said.

“They tried to groom us with what to do,” she recalled.

A list of proof-of-life questions were made.

“We didn’t even know that was a term before this,” Doris said.

The RCMP confirmed to the Advertiser that the agency “worked closely with the FBI” and contributed to an FBI task force assembled to free the hostages. The RCMP also confirmed an ongoing investigation but declined to say more.

On Oct. 17, CAM announced the abduction on its website and news quickly spread that the group members were victims of a brazen abduction outside of the Croix-des-Bouquets suburb by the 400 Mawozo gang, which threatened to kill the missionaries unless a $17 million ransom was paid.

According to the Haiti-based Center for Analysis and Research in Human Rights, a video was published on Oct. 21 announcing that the 17 missionaries “each had a weapon aimed at their heads and would be executed” if the ransom was not paid.

CAM has a no-ransom policy, however, Phil Mast, a CAM Haiti country supervisor, stated in a Dec. 26 testimony at a church in Tennessee, that a ransom had in fact been paid with money from a donor “who offered to take the negotiations and deal with the situation … and it was turned over to another party to deal with it.”

It’s unknown how much money was involved or how payment – if there was any made – was facilitated.

CAM spokesperson Weston Showalter declined an interview with the Advertiser.

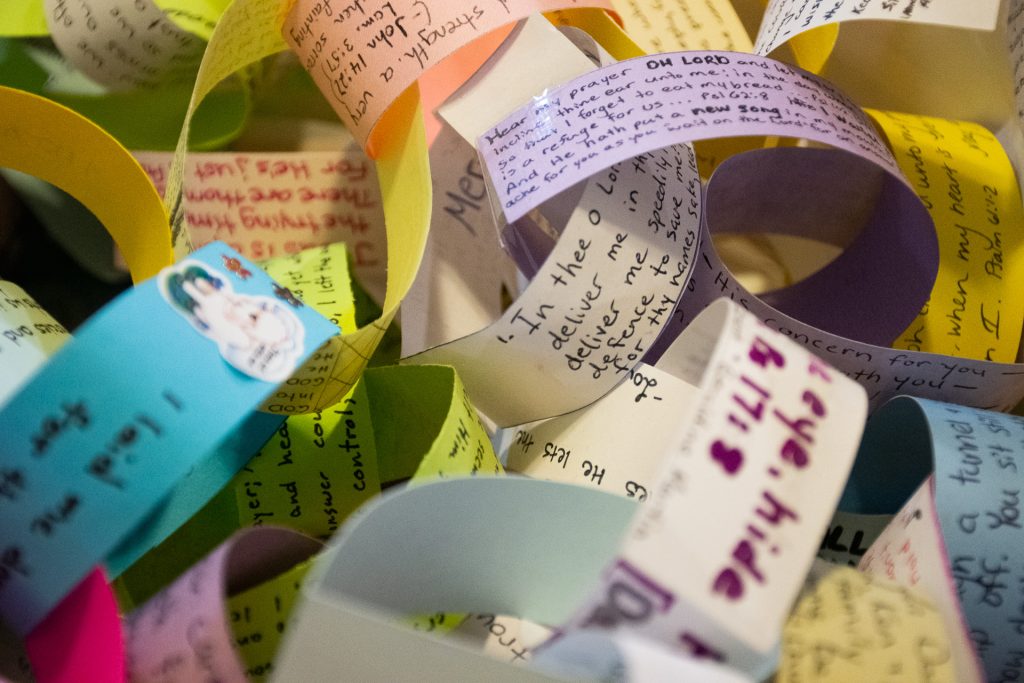

The Wideman’s church community came together to pray for the family and offer encouragement in the form of a “prayer chain” with messages of encouragement, prayers and scripture written on over 1,000 pieces of paper. (Photo by Jordan Snobelen)

Twice-daily phone calls were held between CAM and the affected hostage families, with CAM officials conveying whatever information they could, Doris said.

Details were limited at best and long stretches went by without any proof of life, Doris said, but the calls were a “lifeline” for her and Ken.

“One of the hardest things was the information that we did get, we were not supposed to share that and we understood the reason for that, but oh that was hard,” Doris said.

Support flowed from their church community.

Messages of encouragement, prayers and scripture were written on over 1,000 pieces of paper formed into connected loops and stapled together into a “prayer chain.”

“Anybody we talked to was very concerned about us,” Ken said.

“Maybe we did crash a few times, but we always got back to the fact that we do believe that God is taking care of [Dale] … that always helped us to carry on and try to accept that we may never see Dale again alive.”

“We knew he was going to a dangerous country, but who was I to say he can’t go?” Doris said.

Meanwhile, in Haiti, the missionaries were about to spend their first night in captivity, one with little sleep.

IV: Days of prayer and song

The next day, a Sunday, the group was permitted outside.

“Which was a surprise to us, but it was real nice,” Wideman said, adding that the group was heavily guarded.

Six gangsters would loiter in the daytime, and around nine at night, drinking, smoking, ingesting drugs, practicing the Haitian Vodou religion, and playing music the missionaries found “obnoxious.”

The missionaries were provided couches and chairs to sit on outside, but a hanging tarp blocked any view from a nearby roadway and any breeze that might have provided relief from the heat. The group ate two to three times per day, were brought clothes and could rinse.

Most days were “terribly boring,” Wideman said. The group fell into a daily routine of mornings filled by prayer for deliverance, safety, health and for the gangsters, who Wideman said “live just terribly meaningless lives.”

“We did a lot of that because there was nothing else to do,” Wideman said.

Allowed to keep their wristwatches, they began praying around the clock in rotating half-hour shifts.

The group also sang the words of hymns like the Power of the Blood and Angel of the Lord.

“They looked at us really weird for a while … I think they thought we were the strangest bunch they’ve ever seen,” Wideman remarked.

On a Thursday, around a week-and-a-half later, the group was moved to another location mere kilometres away, according to Wideman, for around three weeks before returning to the first location with the Devil’s House.

An aerial view of an urban Haitian neighbourhood. (Pexels photo)

Inside a new house, the rooms were slightly larger and the group had access to bucket showers with more privacy.

“We could tell that they felt a little insecure; at night they would now lock us up all inside,” Wideman said.

“Sometimes they would shoot right outside the house to scare people off.”

Outside there were mango and coconut trees, the space was cleaner, had a breeze and farmers laboured under the hard sun in surrounding fields.

Wideman noticed planes coming in for landing at the capital’s Toussaint Louverture International Airport, flying low enough overhead for their landing gear to be visible from the ground.

“Haiti doesn’t have many planes,” Wideman said.

So, when he noticed one particular plane flying circles overhead, appearing several days in a row, Wideman became hopeful.

But the stay wasn’t without tribulation.

The group began developing sores, like “nasty boils,” Wideman said. He had a red patch still visible on his forearm from one of the sores a month after the ordeal.

Stoltzfus, one of the other missionaries, also upset one of the gangsters after chucking a bottle he was told not to touch, lest Satan bite him.

The gangster threatened to shoot Stoltzfus in an hours-long ordeal Wideman described as an unnerving and exhausting “battle between light and darkness.”

On Nov. 19, the group was moved back to the first location, this time granted more freedom to walk around the entire property.

That weekend, Matt, a man in the group, was without medicine for a health condition and lay writhing on the ground.

Garbage is seen strewn along a road in Haiti. (Photo by Dale Wideman)

“He was laying down inside and he was just shaking and could hardly talk, and just sweating, and I think a lot of us thought ‘we’re watching someone die,’ he looked terrible,” Wideman recalled.

Matt, and his wife Rachel, would be the first of the hostages to be released, purportedly because of Matt’s condition.

The following two weeks were a low point for Wideman. A pen he used to keep a diary on paper towels had since run dry, contributing to Wideman’s worsening mental state.

“It just seemed there was no hope, we were starting to think ‘we’ll be here forever,’” he said.

Talk of escape began, but not all were on-board.

The next month, two women and a six-year-old were released, possibly because of their health. The group was now down to 12 people.

“We had been there two months now and we’re getting extremely desperate and there seemed to be no action,” Wideman said.

But for an escape plan to work, they had to be united.

V: ‘It’s possible, we can do this’

The next day, Yoder explored the perimeter’s thorn bushes and found a good spot to escape.

“He came out of there and he had a big smile on his face, he just said, ‘Yeah, it’s possible, we can do this,’” Wideman said.

One day the group was divided and the next, everyone was together – it was as good a sign as any.

“To us, that was a miracle,” Wideman remarked, feeling God was leading the way.

“Everything changed after that, everyone was all together on this and we were excited.”

The group arranged the exact order of who would exit out the door in the early morning hours when the gangsters kept to themselves.

But the door to freedom was held shut with a wooden post and a large stone at the bottom.

Yoder and Wideman pushed at the door, sending the stone rolling several feet away, where it thudded to a top.

They dove back into sleeping positions on the floor, but no guards came.

The door was opened, and the group entered into the dark with bags of water stuffed into their pockets.

It was Dec. 16 – day 61 of captivity.

“I can’t describe that feeling of stepping out that door when just down around the corner are all these guards with their assault rifles,” Wideman said.

“Once it started, it happened so fast … I couldn’t think about getting scared.”

The group covered upwards of 30 feet of open ground and was into the bushes.

It was the first moment Wideman says he could feel himself relax – if only a little.

The group of a dozen followed a creek, passed around the western edge of Trou Caiman lake and alongside farm fields into a small village, worried one of the many dogs outside would set off a chorus of barking as they slipped past houses in the moonlit Haitian countryside.

“We didn’t know where this gang territory ended, so we were terribly afraid of meeting anyone … we didn’t know who’s sympathetic to the gang and who is actually a gang member,” Wideman explained.

The Haitian countryside seen looking northeast from Fonds-Verrettes, a Croix-des-Bouquets neighbourhood in Haiti. (Photo by Dale Wideman)

A lighted switchback road ascending a mountain range beyond became a landmark, and urban light pollution spilling into the sky gave an idea of where Port-au-Prince sat to the west.

As the sun crested the horizon, the group discovered they had severely misjudged the geography and spent hours trekking in daylight.

The group ambled off a main dirt road, opting for a less traveled cow path.

“It was just kind of a wasteland where we were in,” Wideman said.

Roughyl five hours after their escape, the group came to a main road, Route Nationale 3, outside of the neighbourhood of Bois Dorme, where Stoltzfus and Yoder broke off and met a farmer who directed them to a neighbour with a phone.

VI: Rounding the corner

Barry Grant, a field director, and Mast, the country director, rounded a corner and were met by the dishevelled group waiting at the roadside.

“They come around the corner with the CAM vehicles and it’s just, ‘Wow,’” Wideman said, at a loss for words.

Back within the safety of CAM’s compound, the group talked, laughed and cried.

The building where Dale Wideman lived at, located on the Christian Aid Ministries compound in Haiti. (Photo by Dale Wideman)

Officials from the American and Haitian governments arrived and by 4pm that day, the group was on a U.S. Coast Guard plane, destined for Florida.

The missionaries stayed at a Miami hotel for a couple nights to decompress.

On Dec. 18, Wideman touched down at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport and arrived at his Wellington County home shortly after 9pm, having been driven there in an RCMP truck.

Doris heard the front door sweeping open across the floor and thought, Is that Dale?

VII: Forgiveness

In the weeks following captivity, Wideman has struggled to reconcile his experiences.

“It wasn’t very traumatizing … but it was pretty terrifying,” he said.

“It definitely gives you a different perspective on life.”

Wideman admits his views of Haiti and its people are skewed, but said it’s important to keep in mind the many hardworking, innocent Haitians suffering under the rule of gangsters, corrupt politicians and racketeers.

Daily life in Haiti. (Unsplash image)

“I was feeling like, Haiti, I mean, tough luck … if you don’t want us, then we’ll just leave you,” he said.

Decisions around missions in Haiti need not be made impulsively and in ignorance, Wideman said, but he is unsure where the balance lies.

“I don’t like the idea of just running away, leaving them [to] sit in these dangerous and hard circumstances, when we can just buy a plane ticket and get outta there,” he said.

“There’s so many people there that need help.”

Building in Camp-Perrin, in Haiti’s south. (Photo by Dale Wideman)

Wideman has since returned to his former job as an electrician, but says he would return to Haiti and holds no hatred for his captors.

“If I would just be here harbouring bitterness toward these guys … I wouldn’t be doing as well as I am mentally and emotionally,” he explained.

“To be holding that against them, it’s just not going to get me anywhere. I mean what’s the point?”

Wideman is adamant his Christian faith and teachings are what has kept him going.

“We believe to really solve issues, [it’s] not by retaliation but to return hate with love,” he said, admitting it’s something easier said than done.

“You look at who they are, just as an individual, we got to know their names and you realize that these guys were little boys at one point … they don’t even know what love is … it helps to think more deeply about that they’re real people just like you and I,” Wideman said.

“That’s what really helped me to love them instead of hate them.”

Given the chance to speak to his former captors, Wideman said, “I would like to say a lot of things; I’d tell them that I forgive them.”